Following the Money

Published: March 2024

We met heiress Jane Catherine Gamble in an earlier article, and learnt of her sizeable 1885 gift to the College (see Girton Reflects no.1). Over 2020-21, College set out to trace the complex financial history of this bequest. Our first enquiries uncovered clear links to wealth connected to enslavement, and those findings have framed other articles in this series. Subsequent research has put us in a much better position to spell out the precise routes along which much of Jane Gamble’s wealth travelled. Such precision is all part of the work of accounting.

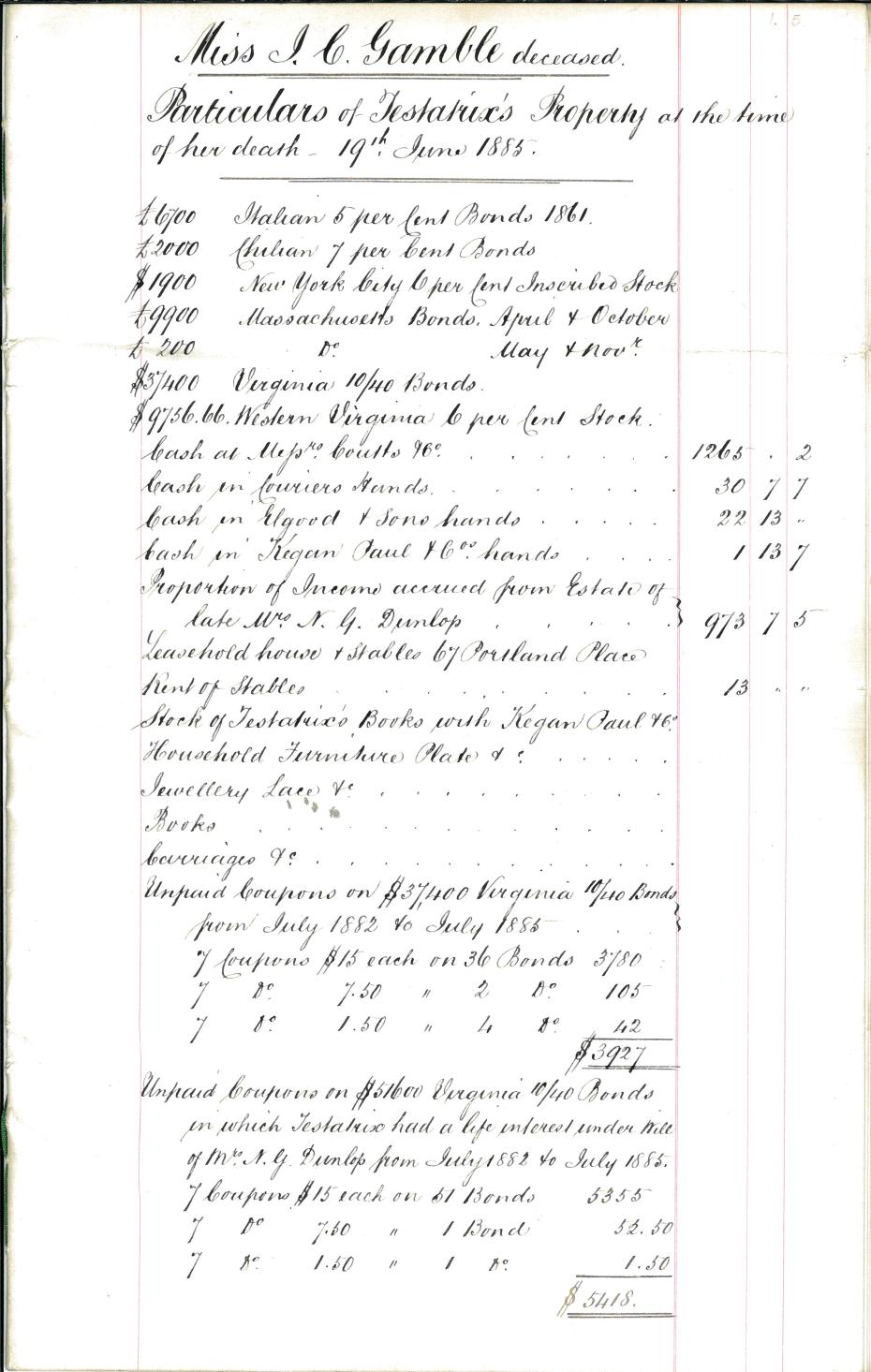

The value of the bequest

When Jane Gamble died aged 76 in Italy in June 1885, her estate was meticulously valued for probate. The total – just over £30,000 – can be calculated to be worth around £3.85 million today.1

First page of a list of Jane Catherine Gamble’s wealth and possessions at the time of her death, drawn up by Farrar and Co, 1885 (archive reference: GCAR 2/6/11pt).

After bills and other bequests were paid, the residue came to Girton. In time, the total value of the bequest was assessed at a little over £19,000. When put toward the construction of a new building, this can be seen as worth around £2.65 million today.2

The bulk of the Gamble bequest was in the form of stocks and securities, but it also included some cash, and the proceeds from selling some of Jane’s valuable possessions. Her jewellery and fine lace raised nearly £4,000, with one emerald and diamond necklace alone commanding £940. The College also chose to keep some of Jane’s belongings, including more than 100 books and several pieces of furniture.

Eventually, just over half of the Gamble bequest came from the sale of Massachusetts State bonds for close to £10,500. But also among the financial assets were a considerable number of Virginia State bonds. Most such bonds, issued by the State decades before the American Civil War, funded the building of roads, railways, and canals, paying healthy returns to contemporary investors. We now know these infrastructure projects not only involved enslaved as well as waged labour, but were also designed to make the plantation and slave-based economy of Virginia more efficient. After the Civil War, the bonds proved highly volatile, and complex to redeem. Girton had to seek specialist advice, and sold the inherited bonds in lots, the last around 1900. In total, it appears those bonds raised just over £3,500.

What Gamble had inherited

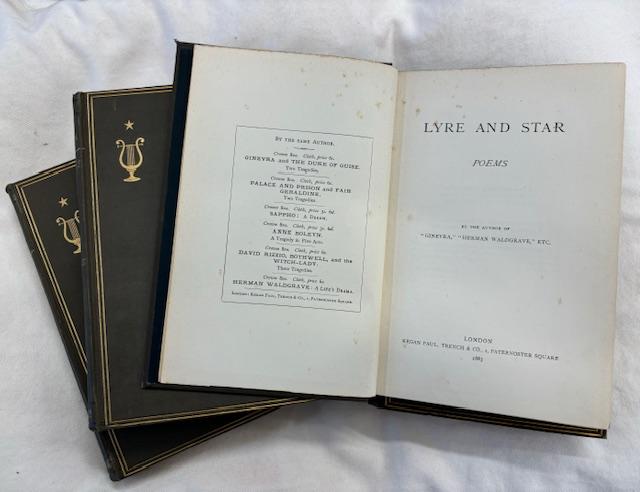

Three of Jane Catherine Gamble’s published works, including two plays and a volume of poetry, Lyre and Star: poems, 1883 (Girton College Library reference: Gamble Collection, 082039). The texts were published anonymously, and it would appear Jane selected the lyre and star as a cover motif.

Jane Gamble was a published playwright and poet, but her writing seems not to have been the source of her personal wealth. While we currently lack direct evidence that Jane inherited money or property from her father, Princeton alumnus and Florida enslaver John Grattan Gamble (d. 1852), we have recently discovered his will and probate documents. These will take some deciphering, and may alter this assessment. However, it remains the case that Jane’s privileged lifestyle was supported by her maternal relatives, the Dunlops, and that her personal wealth in 1885 was largely derived from her inheritance from her aunt Nancy.

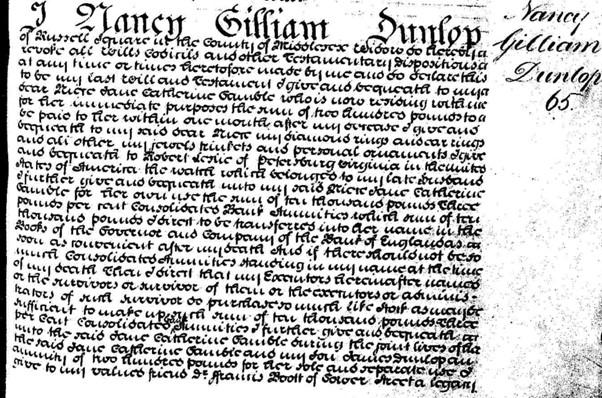

An extract from the will of Nancy Dunlop, signed by her in September 1845, proved on 8 February 1847. The original is held by the The National Archives, London (reference: The National Archives PROB 11/2050/92).

When Nancy Dunlop died in 1847, she left Jane, then aged 39, a sizeable inheritance, yet its full extent remains unclear. Nancy’s will gave detailed instructions about the disposal of her estate: the provision for Jane, personal bequests, life-time annuities for her housekeeper and coachman. To Robert Leslie ‘of Petersburg, Virginia’, a close business associate and relative of her husband, James, and one of the executors of her will, Nancy left ‘the wealth which belonged to my late husband’. This was not further delineated. The rest of her estate, stocks, and securities, apart from one property, she dictated should be sold and the proceeds used to create a trust to benefit her son James, and if he died childless – as happened in 1851 – Jane.

The excluded property is very significant. It was Roslin, the Virginian plantation worked by enslaved labour discussed in earlier articles in this series. That estate, the will decreed, ‘which formerly belonged to my father, and all other [of] the lands and hereditaments adjoining the same which were purchased by my late husband and all the stores, buildings, implements, and utensils whatsoever thereon’, Nancy intended ‘to dispose of by a separate will’. This document has not yet been found. However, some recently uncovered records suggest Roslin may have been left by Nancy Dunlop to Robert Leslie, or to Robert Leslie and Jane Gamble in some combination, or that they both otherwise benefitted from its sale, which appears to have happened around 1853. Up to this point we had believed that Roslin had been sold prior to Jane's inheritance, making her interest in that property less direct. This is the first hint of anything approaching Jane’s ‘ownership’ of a direct interest in the plantation.

All this leaves some things about Jane’s inheritance known, others newly recognised as unknown. In 1847 Jane undoubtedly received a sizeable inheritance from her aunt’s estate, augmented from 1851 by payments from the trust established by Nancy, administered by three male trustees.

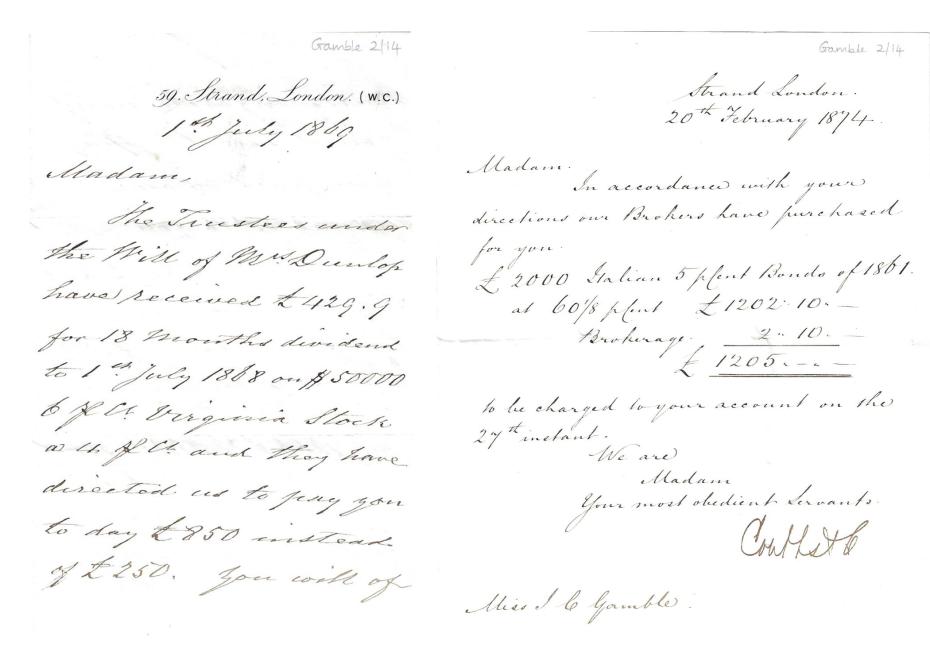

Two letters to Jane Gamble from her bank, Coutts & Co, regarding: a deposit into her account of dividends, and money from the Dunlop trust, 1 July 1869; and the purchase, at her request, of Italian bonds, 20 February 1874 (archive reference: GCPP Gamble 2/14pt).

We do not know the total amount of those payments. But there is good evidence that from 1851 to 1885, Jane received regular transfers from the trust, as well as dividends from stocks and securities in her portfolio. She also seems to have initiated the purchase of new stocks, such as £2,000 of Italian 5% bonds in 1874.

But alongside this documented wealth, there is a fresh issue to address: whether Jane was among those who inherited Roslin in 1847, or whether she nonetheless benefited from its sale circa 1853? Girton Reflects has discussed the conditions of the enslaved people who lived and worked on Roslin. We continue to investigate whether Jane was briefly an owner of the plantation, and we hope recently identified sources in the US will allow us to answer this crucial question.3

Where her inheritance came from

To map the history of Jane’s inherited wealth prior to 1847, we turn to Nancy Dunlop’s life. Nancy was born, probably at Roslin, in 1783, one of three daughters of Charles Duncan and his wife. Another daughter was Charlotte Duncan, Jane Gamble’s mother. In 1800, Nancy married James Dunlop; their only child, James, was born in 1801; around 1802, they travelled to England, and took up residence in London. Their privileged life in Britain was marked by generous entertaining, European travel, patronage of the arts, and many friendships in affluent and artistic circles. The wealth dispersed in Nancy’s will came directly from the fortune and properties she had inherited from her husband, James, on his death in 1841. This included most of James’s ‘real personal estate, lands, tenaments, hereditaments and promises in the …. United States’.4 It also included Roslin.

James Dunlop was born in Scotland in 1769. Several men so named moved from Scotland to Virginia from the 1750s on, complicating precise identification. Evidence suggests ‘our’ James was connected to a wealthy Glasgow family, ‘the Dunlops of Tollcross’, linked to the eighteenth-century transatlantic trade in tobacco and other plantation crops from Jamaica and Virginia. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, James travelled to Virginia and – perhaps aided by family connections – appears to have forged an expanding portfolio of properties and businesses linked to plantation production and the tobacco trade. In 1808, he became the owner of Roslin. It appears that he also came to own other properties in and around Richmond, Virginia, and sizeable tracts of land in several other US States.

However, a newly discovered US archive catalogue indicates James Dunlop had more extensive business interests than we previously knew. These appear to include: a London-based firm owned in partnership with a brother, John Dunlop, which had links to many agents and enterprises in the US dealing in cotton, rice, and tobacco; a Dunlop business in Paris concerned with the re-exportation of American cotton and tobacco; and shared economic interests with his younger relative, Robert Leslie, who for a time acted as the manager of Roslin, and who was himself an enslaver. This new source also suggests that Dunlop acquired considerable US land previously owned by the firm of Tomkinson and Murray, and eventually had extensive landholdings in Missouri, Illinois and several other western states.

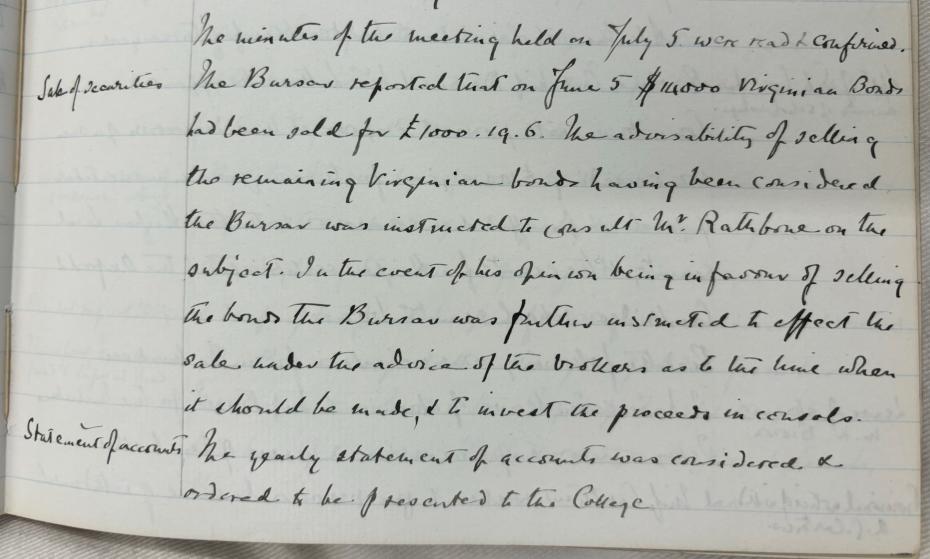

Excerpt from Girton College Executive Committee minutes, 19 July 1889 (archive reference: GCGB 1/2/11pt). The discussion concerned whether Girton should sell its remaining Virginia State bonds.

These discoveries have underlined that James Dunlop seems very likely to have passed on considerable wealth to his widow, Nancy. His will instructed trustees to manage his US properties and wealth, and when appropriate to sell any of these assets and invest the proceeds in the US or in ‘funds Elsewhere’ to support his wife and son. We do not yet know if any of James’s other US properties were worked by enslaved labour, but it must be possible. In the 1840s, he owned, for example, 2,480 acres in Missouri, which was admitted to the Union as a slave state in 1821.5 Significant numbers of Virginian enslavers expanded their holdings, and hence enslavement, into that region in this period.

It seems that a small number of enslaved individuals living on Roslin were emancipated during James Dunlop's time as owner, and (as we saw in Girton Reflects no.8) he discouraged the purchase of further enslaved workers by the estate’s managers. His will stated his wish to confirm earlier emancipations, ‘in case the same shall in any respect have been or become defective’ and his desire that all the enslaved people on his properties now be emancipated. Perhaps James was moving away from unconditional support for slavery from 1810 onwards. Alternatively, he may have seen hiring as an efficient way of maintaining labour, or have been making a business decision based on the political climate and how elderly many of the Roslin residents were. We continue to seek to uncover what happened after James’s death.

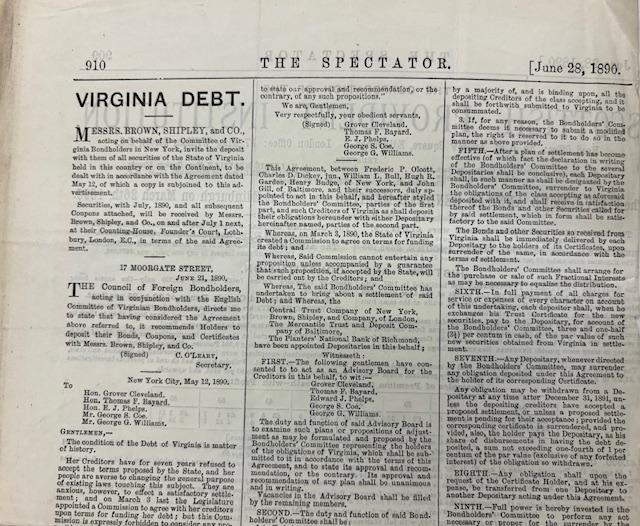

Extract from, ‘Virginia Debt’, an article in The Spectator, 28 June 1890. This was clipped by Girton Bursar, Mary Pickton, and added to the Executive Committee minutes for 4 July 1890, which saw discussion of the $15,400 of Virginian bonds still held by the College. The article reflects the widespread concern about the value and possible sale of Virginian securities. When told that Mssrs Brown, Shipley and Co, ‘acting on behalf of the Committee of Virginian bondholders in New York’, had invited deposits of ‘all securities of the State of Virginia held in this country or on the Continent’, for them to handle, the Bursar was instructed to deposit Girton’s bonds with the firm (archive reference: GCGB 1/2/12pt).

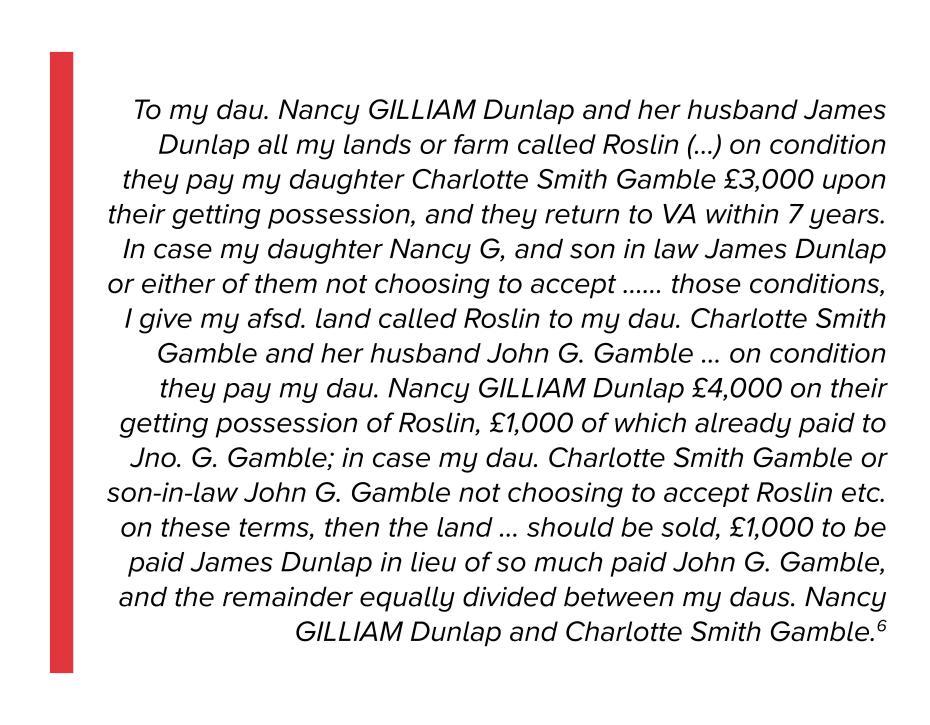

It is newly clear that we do not yet know enough about James Dunlop’s wider wealth and businesses. But our knowledge of his 1808 acquisition of Roslin takes one strand of our map of Jane Gamble’s wealth back to the turn of the century, and to Charles Duncan, her maternal grandfather. In his will Charles gave:

While the will emancipated several enslaved individuals at Roslin, in language that now shocks it also stipulated who would 'inherit' the remaining enslaved workers living there. James and Nancy took over Roslin after Charles' death in 1808, despite the fact that they didn’t return to Virginia. They also inherited a share of the rest of Duncan’s wealth, including ‘stock in the Bank of VA (Virginia), the loan office, the Commercial Insurance of Norfolk, my shares in the Appomattox Canal, and in the Lower Appomattox Co…’. All would have augmented their wealth.

Reflection

Following the money also means bringing more people into the story. The currents of commerce are seen more clearly, and we have uncovered links across the Atlantic that fill in the background to the Gamble bequest. To what we knew about the Dunlops’ affluence being intimately connected to enslavement on the Roslin plantation, we can add wider interests connected to the production and trade in tobacco and other plantation goods elsewhere in the US and the UK. This is not just adding further detail; it is changing the questions that need asking.

Coming Next: No. 10, May 2024

Girton's Early Donors

An internal perspective on the crossovers between the College's ambitions and its financial precarity during the first eighteen years.

Citations

- Respected systems of calculation for the present-day value of past amounts propose this would be worth today between £3.85 million (retail price index), £17.3 million (average earnings) and over £60.4 million (relative output worth). The first has been used here, as it represents the ‘average price’ of goods and services purchased by a ‘typical household or consumer’ in the year in question, and calculates the cost of the same today, allowing for inflation. See: https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/

- The same calculations as above give a range of modern value for the bequest, from £2.44 million (RPI) to over £38 million. We have chosen £2.65 million, calculated using the ‘GDP deflator’ method, seen as most appropriate when assessing the value of a ‘project’ – the construction of a building, present-day costs of materials and labour, etc. See https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/

- But even if no money from the sale of Roslin went to Jane in 1847, or entered the Trust, it remains very possible that income generated by the estate helped support the Dunlop household up to the 1840s or was re-invested in the stocks and securities which contributed to Jane’s complex inheritance.

- Will of James Dunlop, proved on 24 Dec 1841, held by The National Archives (reference: The National Archives PROB 11/1954/439). The will stated that James’s US properties ‘not hereinbefore divided and bequeathed’ were left to his wife and son. We do not yet have knowledge of these other possible bequests, but Nancy’s will and other documents lead us currently to believe she inherited the bulk of James’s US properties.

- Prior to 1821, there was already enslavement in the Territory of Missouri, which was very much larger than the subsequent state. We do not yet know when James Dunlop acquired these acres, nor when he bought any of his other land holdings outside Virginia.

- Will of Charles Duncan, January 27, 1807, Estate Records, Chesterfield Co. VA Wills 1795-1850 (Index 1749-1947 on FHL film 30,870) 7-45/48. Note that Dunlop is spelled Dunlap.