Girton’s early years: ambition framed by financial precarity

Published: May 2024

Girton’s rapid foundation and early growth were both remarkable. Fundraising began only two years before the College opened in 1869 with five students, the Mistress and two women servants. A decade later, 54 students, three resident academic staff, a housekeeper and around six maids lived in the new buildings at Girton; by the beginning of its nineteenth year, in October 1887, College numbers stood at 98 students, six resident academic staff, and some ten domestic employees. Those students lived in four ‘wings’, studied in the College science laboratory and Stanley Library, and entered Girton through the new Tower gateway. The Gamble bequest, as described in the last episode (Girton Reflects no. 9), had underwritten the whole Tower Wing. In acquainting itself with Girton’s foundation, and not least women’s involvement in its funding, the Legacies of Enslavement enquiry found itself wondering about all the earliest donations.

‘Financial precarity’ best conveys College’s situation in its first decades. The plan for eventual self-sufficiency through student fees (£105 a year) did not account for buying land, equipping new premises or creating scholarships, nor for pursuing successive rounds of construction. In the absence of public funds, the founders relied above all on private philanthropy. Fundraising was urgent and continuous, and debt and related interest payments cast a persistent shadow. Deft financial manoeuvring, notably by Emily Davies, was regularly necessary. Careful record was kept of every transaction.1

Appealing for funds

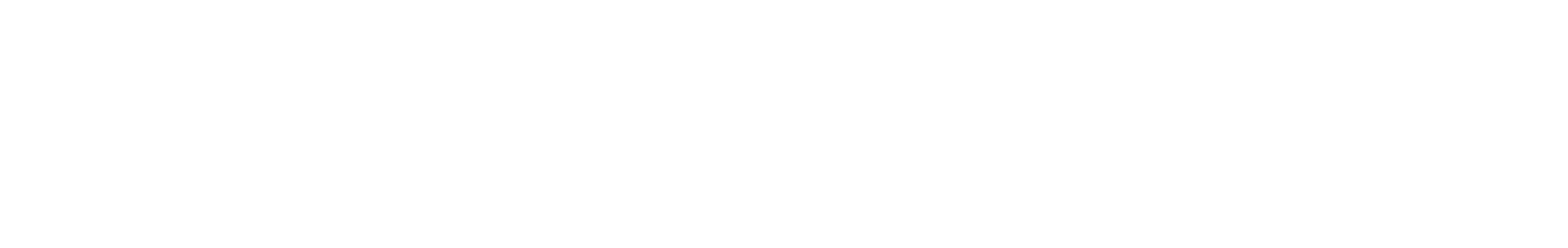

Excerpt from an early fund-raising circular published by the College Committee, late spring 1869 (archive reference: GCCP 7/2pt).

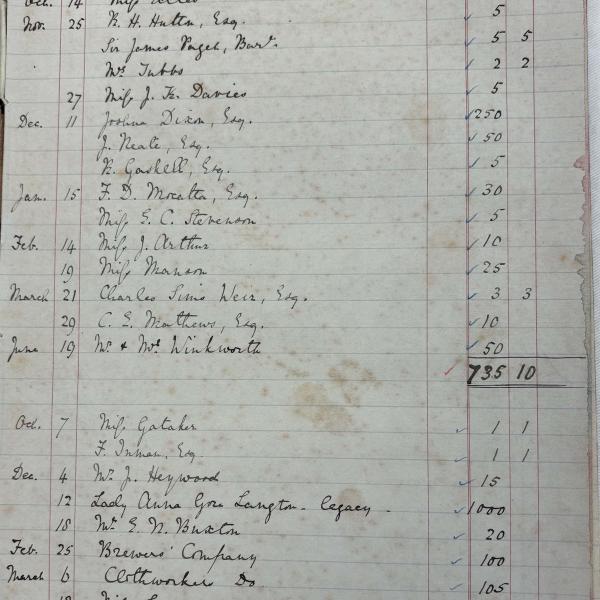

The key fundraising method adopted from 1867 onwards was widely published appeals for individual ‘subscriptions’ or ‘contributions’. Emily Davies and other leading supporters also made more personal approaches across their social networks. Girton did not share the advantages of recent Oxbridge foundations for men – very large initial private endowments or quickly successful appeals that allowed immediate building on a substantial scale. The early hope of raising at least £30,000 to build from scratch proved over-optimistic, hence the decision to open in rented premises while fundraising continued. Despite rising subscription numbers, buying the Girton land in 1872, commissioning the professional architect Alfred Waterhouse, and appointing builders was only made possible by a loan of £5,000 from 22 private 'guarantors' (8 women and 14 men).

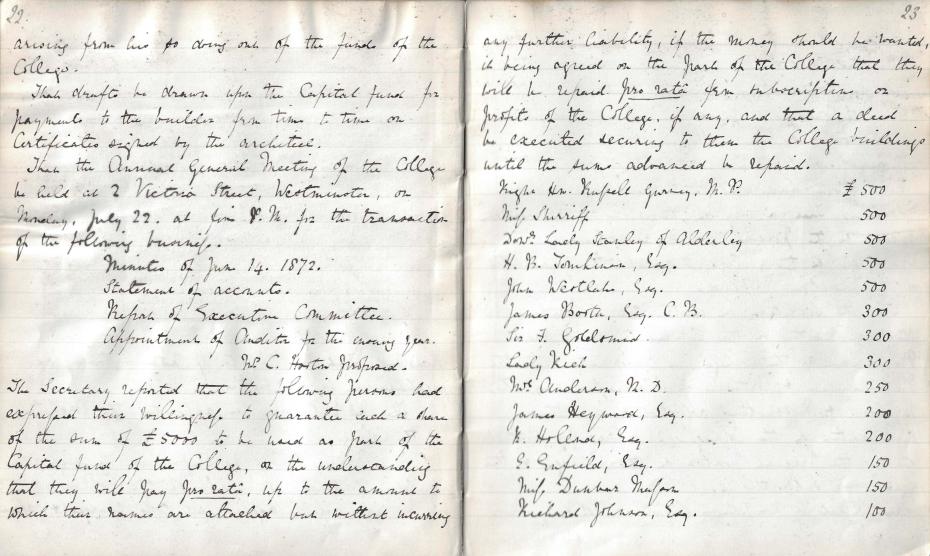

Extract from Executive Committee minutes, meeting of 5 July 1872, listing some of the guarantors (archive reference: GCGB 2/1/3pt). Each individual guaranteed to provide the sum agreed, in sections, as building costs for Old Wing mounted. Most subsequently turned all or part of these guarantees into permanent donations.

The 1873 move to Girton left the College in debt and by December that year it had taken out its first formal loan, at 5% annual interest. Yet by the summer of 1885 – less than 18 years since the public campaign began – there had been three further rounds of building. Each was preceded by renewed fundraising; each cost more than initial estimates. But Emily Davies’s vision remained undimmed, and the College campaign was attracting donors. Between late 1867 and the completion of Tower Wing in 1887 at least 608 individuals sent donations.2 Most allowed their names to be published, a few gave anonymously. The majority made open gifts; a minority gave for specific purposes, generally scholarships. A small number promised sums to be transferred in sections. Every gift, however small, was meticulously recorded, most in Emily Davies’s neat hand.

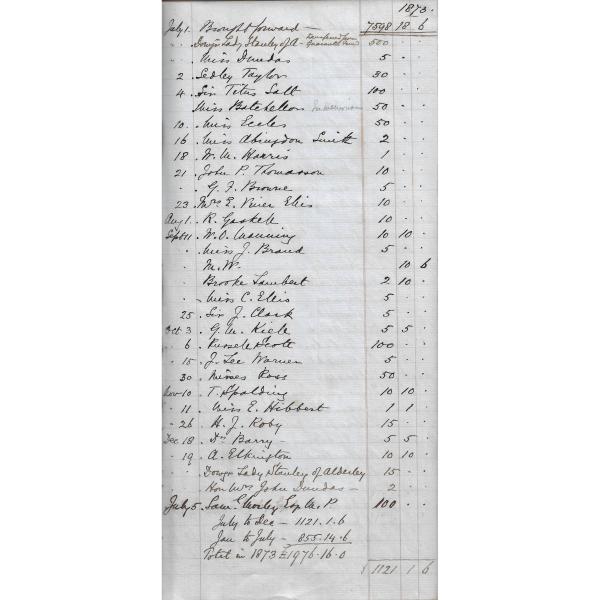

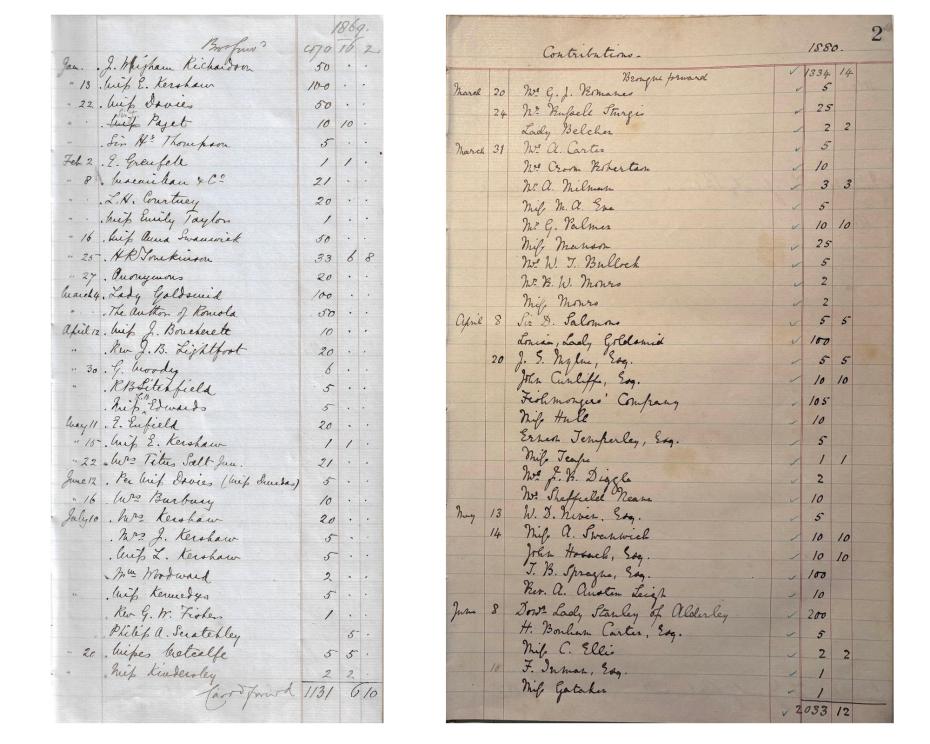

Two lists of donors, 1869 & 1880 (archive reference: GCAR 4/1/2pt & GCAR 3/1/1/1/3pt).

The number of annual gifts, and totals donated, varied markedly; the first did not always correlate with the second, and a particularly successful year rarely presaged similar revenues in the next. The challenge of paying unexpected bills, or the next round of builders’ invoices, was ever-present. Sometimes Emily Davies borrowed sums from scholarship accounts to meet immediate needs. The opening months of the campaign in late 1867 saw just four women and two men donating (or committing to), and a total received of £14.06. However, this excludes the £1,000 promised by Barbara Bodichon, transferred in tranches over successive years. Another 1867 donor was Anna Jemima Clough, later first Principal of the young Newnham College (10 shillings). Twenty-five people donated in 1868, forty-seven in 1869. The largest number of annual donors up to the end of 1887 comprised the 145 of 1872, who gave a total of £2,487, but in most years there were significantly fewer – 22 in 1875, for example; 17 in 1879.

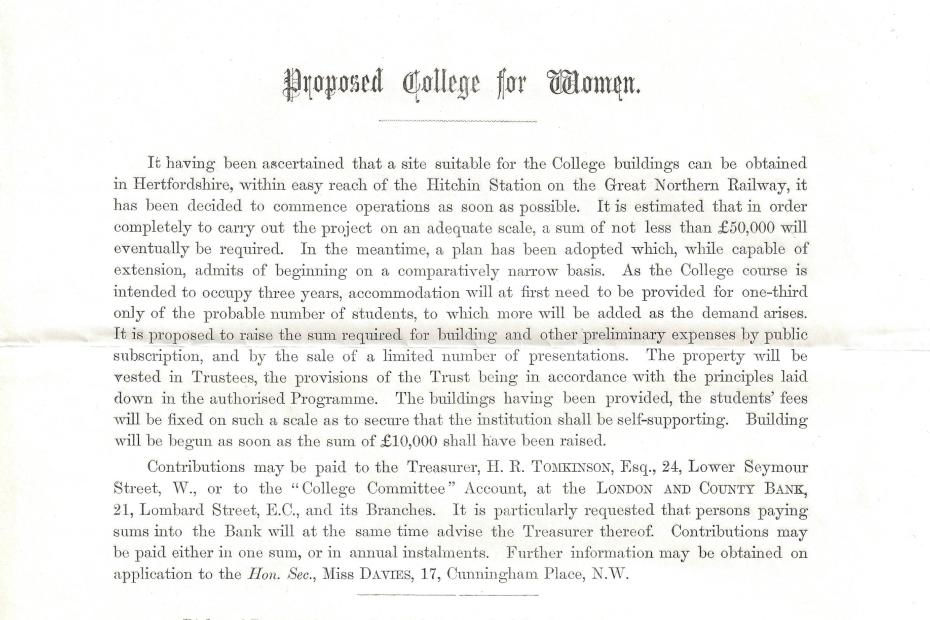

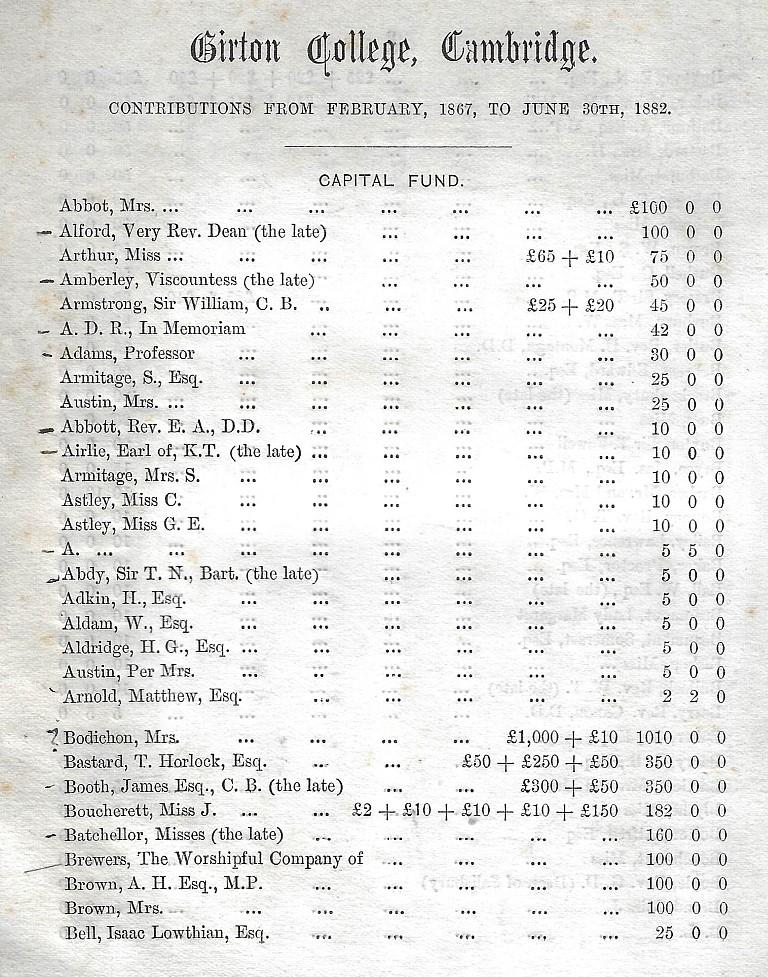

First page of a printed list of all College donors, 1867–1882 (archive reference: GCAR 4/1/5pt).

The constant background of financial anxiety became more pronounced in the late 1870s, after three spurts of building and with a fourth underway. Despite receiving gifts totalling £4,157 in 1877, in 1878 the College had to take out a mortgage of £5,000 (at 4 ½ % interest). This was paid off in 1881, but the building work of 1883–85 cost £16,000, and brought renewed financial worry, exacerbated by a marked decline in donor numbers. Although 62 people gave in 1883, in 1884 that number was seven; in 1885 only three. By early summer 1885, Girton was close to £9,000 in debt, and the annual report noted that interest payments were ‘a heavy drain on … resources’. However, things might have been much worse.3 The news of the Gamble bequest in 1885 meant that although that year witnessed the smallest number of donations since the campaign’s start, it would unexpectedly see the greatest amount donated.

The largest early donation by a considerable margin was Bodichon’s 1867 promise of £1,000. Up to 1872, the next three largest contributions also came from women: £315 each from Mme Belloc, formerly Bessie Rayner Parkes, and a Mrs Abbott; £210 from a Miss Laura Soames. Philanthropist MP and social reformer James Heywood had given the largest gift from a man by that point – £152. Thirteen other people – 4 men and 9 women – each gave between £100 and £105. Barbara Bodichon’s first gift remained the most substantial single contribution until 1877, when former student Eliza Minturn, daughter of a New York businessman, gave £2,000 to establish a College scholarship. Other donors whose gifts were central to the success of the College included Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley (at least £3,695 by 1887) Lady Louisa Goldsmid (£2,420); Emelia Russell Gurney (£1,157), Lady Anna Gore Langton (a bequest of £1,000), and Richard Wright, a Fellow of Christ’s College Cambridge (£1,200).

Lady Louisa Goldsmid (1819–1908), feminist, supporter of women’s education, and early donor to Girton College. This photograph was taken by Window and Grove, photographers of London, no date, but possibly mid-1870s (archive reference: GCAR 11/1a/20/96/2).

However, only a small minority of Girton’s early donors offered sums such as these; the great majority gave £100 or less. Of the 69 ‘subscribers’ by the end of 1869, 60 gave £50 or less in their first gift. The smallest amount given was the 2 shillings from a Miss Kennedy, although over time she would give contributions totalling £25. This pattern continued to 1887. Of the 608 individual donors across the first two decades, 90% gave £50 or less in their first donation, and 66% gave £10 or less. The most common gifts from 1867 to 1887 were of £5 or £10, although such donors sometimes gave similar amounts in several subsequent years. These were not small amounts to contemporaries: £10 in 1885 can be calculated to be worth around £660 today, and the sheer number of these more modest donations made them very significant. Prior to the Gamble bequest, individual gifts of £500 or more produced close to £13,500. Sums over £500 had also been given by several livery companies. But donations of less than £500 certainly made up at least £16,000 of the total received – so close to half of all the money raised up to 1885.

Women as donors

Lists of donors for 1873 and 1878-79 (archive ref: GCAR 4/1/2pt & GCAR 3/1/1/1/3pt).

It is striking that nearly half (46%) of individual College donors from 1867 to 1887 were women. In the first years of the campaign, women formed an even more significant proportion: in each year from 1867 until December 1872, women outnumbered men, in total accounting for 58% of donations, and 52% of donors. In only one year before 1876 did more men than women send money. This pattern then started to change, and from 1876 to December 1882, significantly more men than women made one or more donations. (This would be reversed once again in the 1890s and early 1900s as many former Girton students became donors.) Once the Gamble bequest is included, the total amount given by women exceeded that given by men.

This predominance of women raised certain issues for College’s enquiry. In Girton’s early years, British women of the middle and upper classes had little opportunity to earn significant sums of money (expanding opportunities in school teaching brought relatively low salaries). Instead, female wealth of a size to underpin significant philanthropy was almost always inherited – from parents and grandparents – or came through marriage. But women’s control over their money was often limited by male members of their households. Until the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, a married woman’s money was generally under the control of her husband. Even after 1882, married women’s independent access to money would have varied markedly. There were exceptions, and Girton benefitted from one in the person of Mme Bodichon, but such independence was rare. This may explain the prominence of single women and widows among Girton’s early female donors. It also means that to seek the origins of women donors’ wealth we have had to consider generational inheritance and the sources of husbands’ incomes.

Despite knowing their names, the great majority of Girton’s early donors, listed so carefully by Emily Davies, remain otherwise anonymous to us. Some members of more privileged circles can be traced – people such as the Dukes of Cleveland (who gave £20 in 1882) and Devonshire (£50, 1880); Lady Crompton (£10, 1871), and the Dowager Lady Hatherton (10 guineas, 1884). But the great majority appear to be members of the middle classes. There are visible connections to liberal politics, to evangelical Anglicanism, to prior feminist activism, to the Quaker movement and, of Cambridge colleges, to Trinity. However, the identities of many donors currently remain obscure.

A few examples give a flavour of those more modest supporters who have been traced, and may hint at wider patterns. The first student to donate was Frances Müller, daughter of a merchant, who gave £25 in 1874 as a Girton second year. A small number of former students became donors in this period, including future Mistress Elizabeth Welsh, whose father had been an Irish landowner and linen merchant, who gave her first gift (£5) in 1877, just after becoming Resident Lecturer in Classics, and Katharine Smith, daughter of an Anglican clergyman, who in 1883, three years on from Girton, and teaching at Preston High School, also gave £5.

Several donors were involved in girls’ and women’s education more broadly. Frances Buss, for example, founding Headmistress of North London Collegiate School gave £20 in 1876, and another £10 in 1883; Maria Grey, co-founder of the Girls’ Day School Trust, gave £25 in 1869, and a total of £135 by 1882. Miss Nessie Brown gave several gifts, starting with 10 shillings in 1874 to contribute to a scholarship for a young woman performing well in the ‘Local’ examinations, followed by £21 in 1883 for general uses.4 Nessie’s family had established a department store. Never married, active in local charities, Nessie was among the founders of The Queen’s School, Chester.

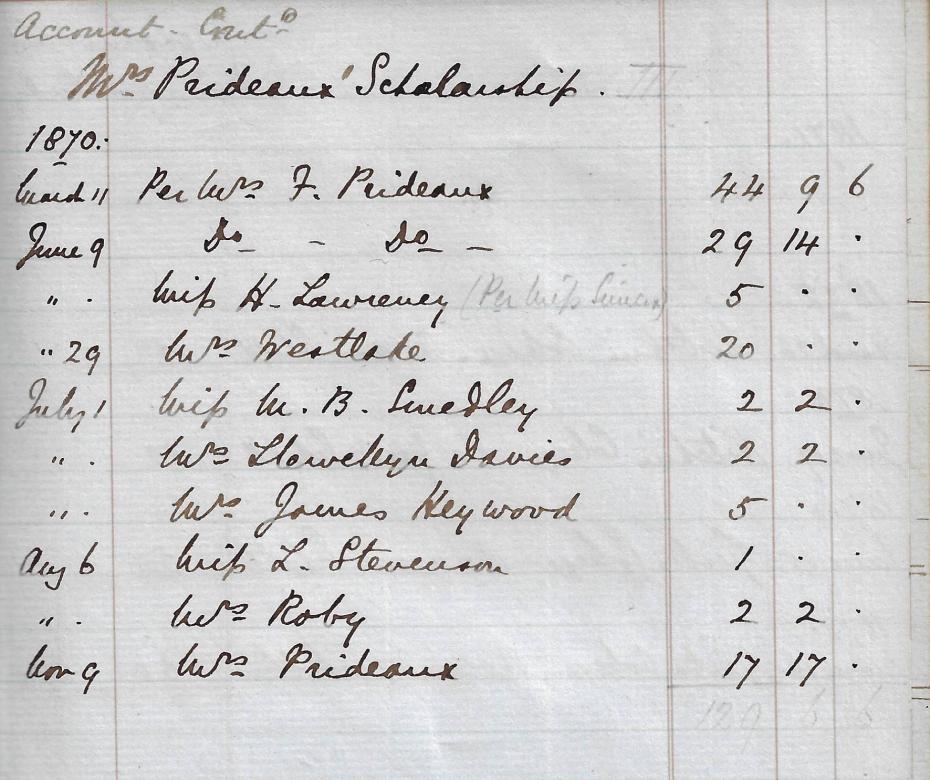

Contemporary College record of ‘Mrs Prideaux’s Scholarship’, listing sums she collected from a group of women, March-November 1870 (archive reference: GCAR 4/1/2pt).

Fragmentary details of a few other early modest donors have been uncovered. We know a little, for example about ‘Mrs F Prideaux’, who is recorded giving a series of small amounts herself, but who in 1870 gathered up donations from several other women to create one scholarship. We believe this is Fanny Prideaux, born in Somerset to Quaker parents, married to a solicitor, and a published poet who later lived in Milverton in the county of her birth. But for many donors almost nothing has been retrieved. Should this matter to us? Does the limited size of their gifts mean such people do not require our attention? Or should possible links to enslavement be pursued, whatever the donation?

Reflection

The large number of relatively modest subscribers to the College cause was indispensable to its foundation. Emily Davies kept meticulous lists of everyone – from those who donated as little as two shillings, to those who gave thousands. Many of these lists were published, often in the yearly Girton Report. They proclaimed the vitality of the College project even when internal accounts were tight, and helped make the case for each new expansion of the enterprise. The same documents also present us with a further set of lists linking the College to individuals whose histories we struggle to uncover. These columns of names do not carry the shock or the weight of the lists of enslaved individuals now known to be connected to Girton. But they are still shaded by the unknown, the currently unseen. Whether more should be done to scrutinise these ‘new’ names in our history is a question still to be answered.

Coming Next: No. 11, July 2024

Alfred Waterhouse and family

How enslavement disappears from view: cotton wealth, abolitionist aspirations and professional fame over three generations of Waterhouse men.

Citations

- On the social and economic backgrounds of supporters of the early women’s colleges (particularly Girton and Newnham), and the financial challenges those faced, see Gillian Sutherland, ‘The movement for higher education for women: its social and intellectual context in England, c. 1840-80’ in P J Waller, Politics and Social Change in Modern Britain, (Brighton, Harvester Press) 1987, pp.91– 116.

- Many donors gave only once, but a sizeable number gave on several occasions. This article in general discusses dates and amounts of ‘first donation’, and, with some exceptions, does not include the total amounts given by more modest donors. The College also received some institutional support, particularly from certain City Livery Companies, notably the Clothworkers’, Goldmiths’, Skinners’ and Drapers’ Companies.

- In 1884, Barbara Bodichon – perhaps responding to worried appeals from Emily Davies – pledged a further £5,000. Initially recorded internally as a loan, this was transferred to ‘donations’ on Bodichon’s death in 1891.

- The ‘Locals’ were examinations intended for students leaving school first set by Cambridge and Oxford Universities in the late 1850s (in Cambridge, run by the Local Examinations Syndicate). They were sat ‘locally’. Emily Davies had been to the fore in the successful campaign in the mid-1860s to allow girls to sit the Locals.