Plantation Life in the 19th century

Given the subject of this article, readers should be aware that what follows contains descriptions and images some may find upsetting.

Published: July 2023

How might one convey something of what ‘chattel slavery’ meant to those most affected?

Three distinct sets of cultures and conditions were experienced by people enslaved on plantations connected in the nineteenth century to Girton. The contexts of their lives differed according to the plantation’s geographic location, the labour systems in place, crops grown and dynamics with enslavers. In fact, where persons were enslaved was the greatest determinant of their expectations, lifelong health and material possessions, not to speak of language, religion, family and community.

The three contexts relate to plantations in Virginia, Florida and the Caribbean. The first is connected to Girton through the inheritance that Jane Catherine Gamble (see Girton Reflects no. 1) received from her aunt on her mother’s side. In the late eighteenth century that plantation primarily produced tobacco, but in the following decades output became more varied, including wheat, cotton and livestock.

The second context concerns plantations in Florida that Jane’s father and paternal uncle went on to develop, so there is a personal connection through her. However, that is the extent of the connection – as far as we know, she inherited nothing from this side of her family. After experiments with the major staples of cotton, tobacco and sugarcane, around the 1830s, sugar became the focus of the Florida holdings.

Finally, in the complex background to Gwendolen Crewdson (see Girton Reflects no. 3), the Waterhouse side of her family, from whom she may have inherited part of her personal income, had profited handsomely from commercial (trading) interests and links to plantations in the Caribbean, including Guyana. Here, in the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the principal crop was sugar, while over this period cotton diminished in importance.

Virginia

According to census records for the year 1790, Virginia had more enslaved persons than any other state in the new United States of America, and more than double that of the state with the second highest number (where South Carolina held 107,094 people living in bondage Virginia held 292,627).

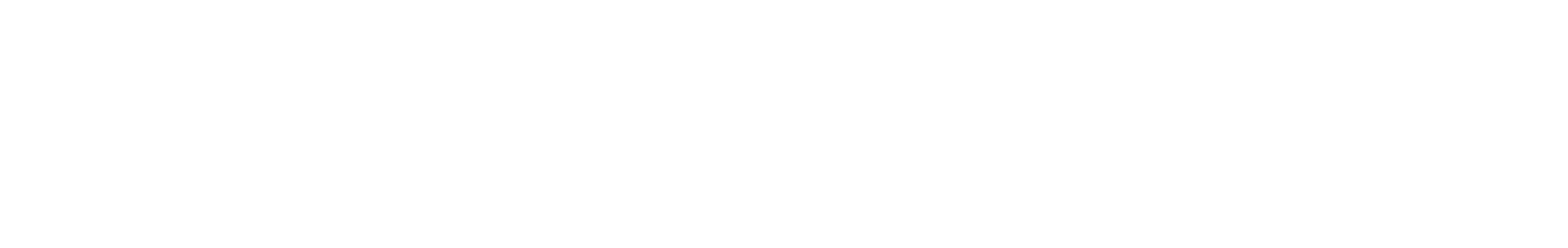

'A Slave Auction in Virginia’, from The Illustrated London News, 16 February 1861. Image held by the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Richmond VA, USA.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Virginia was an established state with significant infrastructure, an enduring tradition of plantation aristocracy and an honorific culture. The mode of enslavement on plantations in the state was largely paternalistic and pronatalist, espousing an estate-wide ‘family’ culture, epitomized in the figure of the paterfamilias as the white owner/patriarch at its centre. Enslaved people were forced or compelled into adopting Christianity, along with Virginian plantation mores, in an active erasure of their own heritage. The culture of plantation slavery in Virginia promoted a hierarchy amongst the enslaved, differentiating those who toiled in the fields from those who worked in the ‘big houses’ as cooks, ladies’ maids, childminders, footmen, and the like. This hierarchy would have been materially visible in garb, provisions and the capacity for hygiene experienced by labourers in diverse positions. Virginian enslaved populations were largely mixed regarding age and sex, which encouraged the development of community and familial structures. Yet the latter were often disrupted through the sale of family members away from one another, the pervasive practice of hiring out enslaved labourers, sexual assaults on enslaved women by white enslavers and/or overseers, forced pregnancies, and through communities being dispersed upon the death of their enslavers.

On working in the tobacco fields, Matilda Henrietta Perry was later recorded describing how sensitive the crop was. To protect it, her master made the women pin their dresses around their necks, lest their skirts damage the plants. She recounted how neglecting to do so would result in a ‘lashin’,’ as would picking any tobacco leaf too early or too late. Due to the need to constantly bend over the plants for tending or harvesting (under the watchful eye of overseers), Matilda remembered feeling her back was ‘ready to pop in two’.

Enslaved people in Virginia constantly lived under the particular threat of being ‘sold down south’ or ‘sold down the river’ to deeper Southern states (for example, Georgia or Florida) where they knew conditions were significantly more brutal and mortality much higher. When interviewed later, the formerly enslaved William Johnson recalled, ‘Master used to say that if we didn’t suit him, he would put us in his pocket real quick— meaning he would sell us’. Plantation owners in Virginia, as elsewhere, often used overseers and managers to distance themselves, as the more genteel planter class, from the day to day operations and from the brutalization – of all parties – involved in chattel enslavement. Ultimately, the work force was capital in human form and individuals were regarded as property with a market value.

The Florida frontier

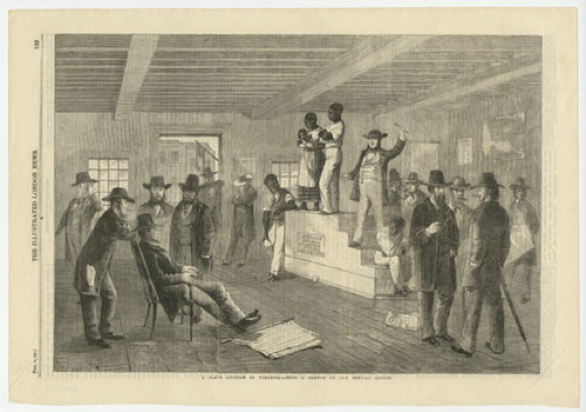

The second distinct context is the Florida frontier from the early to mid-nineteenth century. The Gamble brothers, John and Robert (Jane Catherine Gamble’s father and uncle), both established plantations on the edge of the Florida frontier during the First and Second Seminole Wars (1817-1842). They moved their enslaved populations from Virginia to Florida, by foot and wagon, and then used their labour to settle on what was previously indigenous land. This ripped people away from pre-existing ties without any means to maintain connections. The old, infirm and very young were sold directly or by auction beforehand so as not to hinder the movement of the wagons. During the journey, men and women were forced to walk, carrying the possessions of the white families they accompanied, tending livestock, and seeing to cooking and servicing the camp. ‘Untrustworthy’ enslaved persons were bound, especially at night, to keep them from running away.

American Anti-Slavery Almanac. Illustrations of the American anti-slavery almanac for 1840. New York, New York. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Printed Ephemera Collection. Photograph: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007680126/.

This migration of planters from well-established so-called slave states to the Southern frontiers has since been dubbed by historians as a ‘second Middle Passage’, evoking its brutal parallels with the harrowing journey to which captured Africans were subjected on the ships taking them from the west coast of Africa to ports in North and South America or to British colonial holdings in the West Indies.

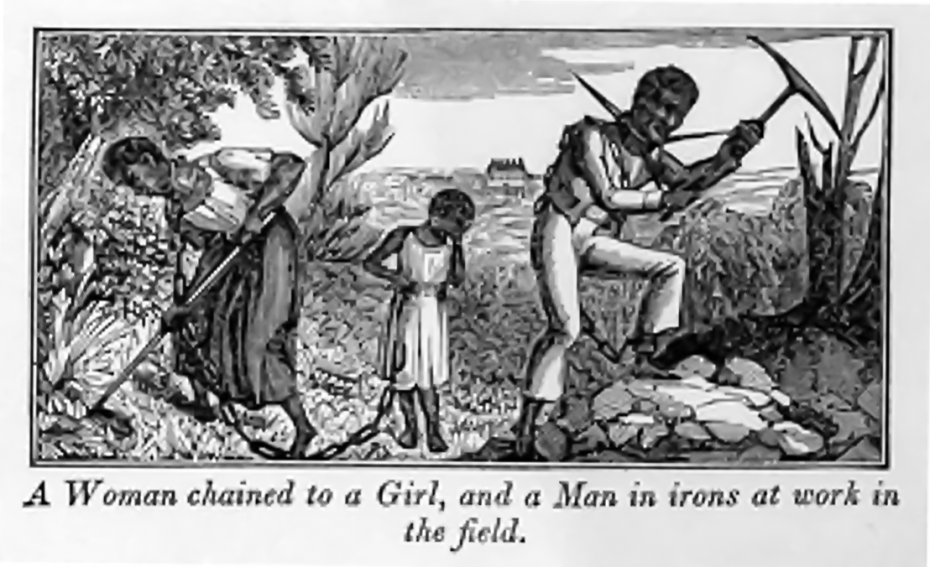

Given the frontier nature of the plantation holdings, the labour performed by the enslaved workforce was backbreaking — clearing terrain of trees and rocks, digging ditches to drain swampland and generally making the land tenable, all whilst going without sufficient shelter and provisions as the new plantations were being established. After sugar was identified as a desired main crop, brick sugarhouses and mills had to be built. Sugar was largely considered the most difficult of crops, given its toll on those used to produce it. Due to the hot, humid climate and swampy terrain in Florida, enslaved labourers were also exposed to unfamiliar illnesses to which they were susceptible.

Describing the sugar mills in Florida, one student historian observes:

how terrible working conditions in the mill would’ve been for the enslaved who laboured there day and night. They would have worked in extreme heat, with explosive machinery, in a building full of tinder, all while being suffocated by an ‘impalpable powder’. It is no doubt that these conditions would have had a huge impact on the health of the enslaved.1

Regardless of crop, most enslaved labourers were expected to work from sunup to sundown; on sugar plantations night shifts were often also required to keep the mills running at all times.

The Caribbean

‘Our’ final context covers locations in the broader geographic region of the Caribbean. The region was typified by the long-established predominance of sugar production and a common overall ethos and mode of enslavement. Here we find some of the early commercial interests of the Waterhouses, and their support of plantations, including ties with planter families through marriage. These interests were largely located in Demerara, Guyana and other British holdings in the ‘West Indies’.

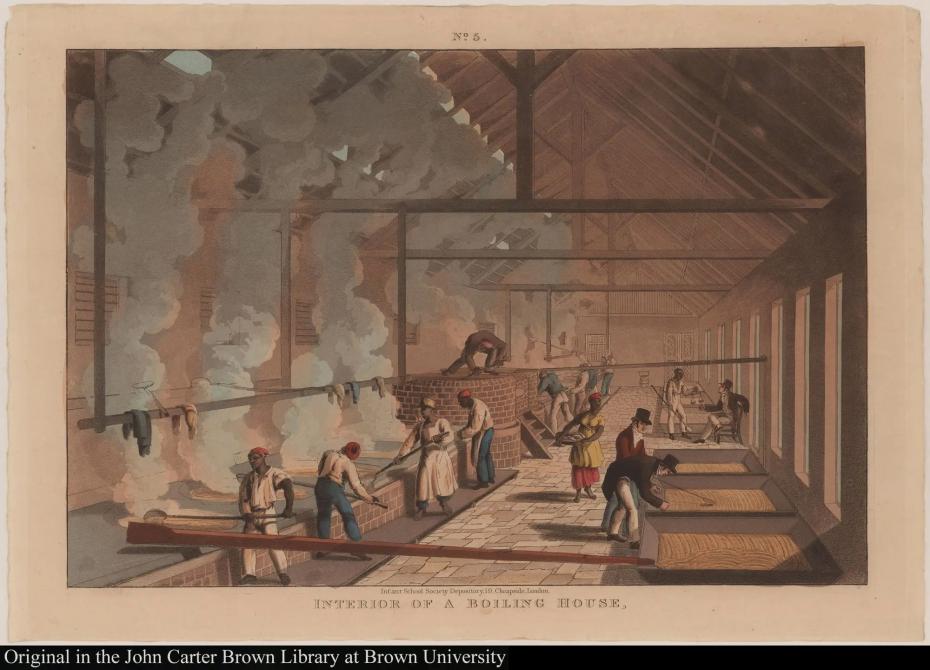

This part of the world was considered the most brutalizing and fatal site of chattel enslavement. Over the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth, the average life expectancy in the West Indies was under 23. More than a half of the people born in Demerara between 1820-1832 died before the age of 15. It was often charged against plantation owners on these islands, by the formerly enslaved and abolitionists alike, that enslavers worked people until they dropped dead -- a characteristic of enslavement practices in the Caribbean that is well documented by historians. Though there are few surviving accounts of enslaved persons from this period and in these locations, those that do exist describe extreme violence and a disregard for human life. In addition to the violence, new diseases and scanty rations, sugar plantations could impose oppressive workloads.

In this region, there seems to have been a lack of obvious familial and community structure, whether among the enslaved population or their white masters. For the enslaved, this resulted in high instances of family separation and a dearth of social connection, cultural preservation or sense of identity. It was in this region that ‘seasoning’ was common practice. ‘Seasoned’ people were those who had survived their first six months in the Caribbean after being captured in Africa. There are accounts of ‘seasoning camps’ where newly seized people were ‘broken’, so that when they were put up for sale they would command higher prices. ‘Unseasoned’ people were cheaper as they were considered a risk, often dying shortly after arriving in the colonies. It was also a strategy for plantation managers and owners in the Caribbean to purchase enslaved people from different African regions and cultures as a way of disorienting and disconnecting them.

'Interior of a Boiling House’, from William A V Clark, Ten Views of the Island of Antigua, (pub. 1823). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence RI, USA.

The white men working on these plantations were more often (than elsewhere) overseers and managers hired by absentee plantation owners based in Scotland and England. It is a recurrent theme in contemporary sources that overseers and managers tended to be more violent and negligent than enslaved populations perceived the owners to be. Due to the roughness of the colonies, few British women were willing to venture there, creating a culture wherein the practice of concubinage, as well as the rape of enslaved women, flourished in the absence of such social and religious restraints as existed in other cultures of enslavement. Describing the conditions of life for Caribbean and Guyanese enslaved populations, one historian characterized it thus:

A new and hostile disease environment, coupled with extreme work loads and inadequate diet, put enslaved Africans and their descendants in the New World in a precarious position. The situation was compounded by miserliness and racism, which induced slaveowners, doctors, and even slaves’ advocates to overlook evidence of slave malnutrition and illness. Slaves were punished for complaining of poor health ... [And] proposed measures for improving slave health and achieving natural increase were ineffective. Racism and profit-seeking were key elements in the demographic debacle of Caribbean slavery.2

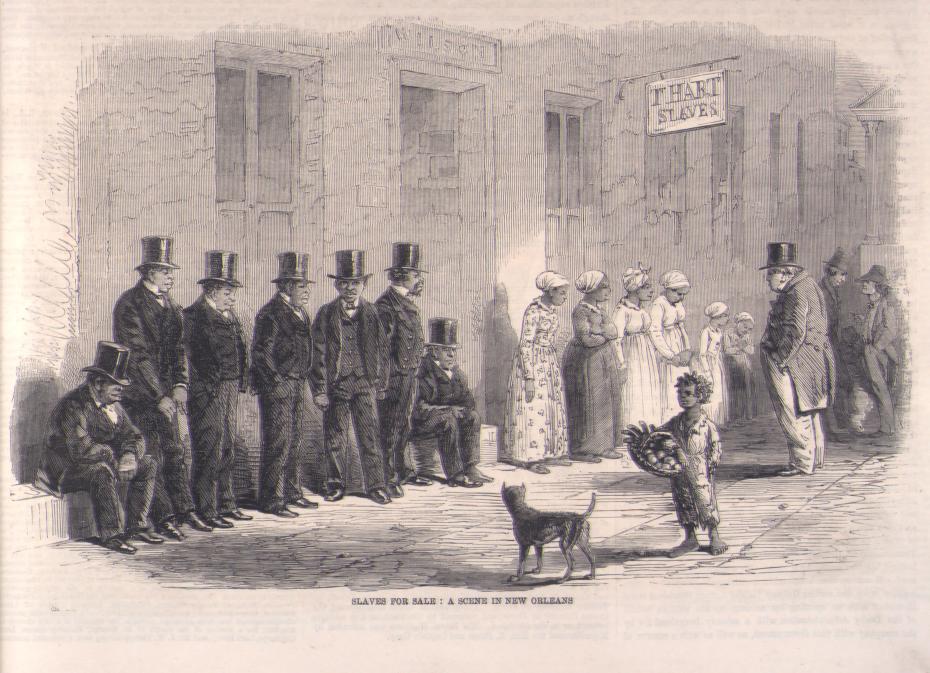

’Slaves awaiting sale, New Orleans, 1861’, from The Illustrated London News (Jan-June, 1861), vol. 38, p. 307. Part of this was used as the cover picture for Routledge's 1972 edition of Barbara Bodichon’s An American Diary, 1857-58 (described in 'Girton Reflects' no.3).

Reflection

This account was compiled from secondary sources to give the initial Working Group some background on everyday life in nineteenth-century plantations of interest to Girton. Some of the extreme conditions that many endured may well have been matched by the ‘damnable barbarity’ of working lives in Britain – the comparison is made by William Cobbett in the 1820s on his Rural Rides through the English shires. There is much room for debate here. What seems indisputable is the way in which enslavement denied people legal, civil and moral recognition as persons. Treating whole persons (let alone their labour) as chattel goods became part and parcel of modern commercial expansion on both sides of the Atlantic. Singular among all the commoditizations that contributed to a modernizing economy, this left a deep mark on future generations.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: July 2023)

Coming next: No.5, August 2023

The abolitionist cause among Girton’s founders and supporters

How Emily Davies and her colleagues linked together educational and abolitionist aspirations.

Citations:

- Litteral, S. Matthew. 2019: 14. ‘An Archaeological Investigation of Enslavement at Gamble Plantation’ (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. (MA Thesis, University of South Florida, published under USF Digital Commons.)

https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8053 - Jabour, Anya, 1994: 17. 'Slave health and health care in the British Caribbean'. Journal of Caribbean History, 28: 1–26, as quoted by Richard B. Sheridan, 2002: 266–67. ‘The condition of slaves on sugar plantations in the colony of Demerara, 1812–1849’. New West Indian Guide, 76: 243–69.