Presences and absences: Roslin, Virginia

Published: January 2024

This is the third episode to draw on the research that led the Legacies of Enslavement Working Group to pay attention to one particular plantation in Virginia. Roslin Plantation no longer exists as a named estate, but its fortunes had a direct bearing on the wealth of the heiress with which this series began. What do we know about the plantation itself?

Roslin’s owners and managers

Girton’s interest in the estate spans the period from 1770s to 1840s, when it was owned by Charles Duncan (Jane Catherine Gamble’s grandfather, who had married into an established Virginian family), and subsequently by James and Nancy Dunlop (Jane’s aunt and uncle). In the late eighteenth century Roslin primarily produced tobacco; by the time Duncan’s son-in-law, James Dunlop, took over the output was more varied, including wheat and cotton, and he experimented with livestock. We met the Dunlops in the last Girton Reflects (no. 7), then absentee owners living in London, moving in well-connected literary and artistic circles. A double portrait, painted around 1825, has their names as its title.

‘Mr and Mrs James Dunlop’, painted by Thomas Lawrence, circa 1825, willed to Girton by Jane Catherine Gamble but then returned to the Dunlop family in Scotland at their request, and subsequently sold. Painting now held in the Worcester Art Museum (Worcester, Massachusetts, USA). Image rights - Worcester Art Museum/Bridgeman Images.

So far, our materials on Roslin come from two periods of estate papers originating with Dunlop’s managers: a letterbook and land records belonging to William McKean (manager 1809-1818), and ledgers, letters, surveyor’s documents from William Henderson (1824-1832).1 Owners and managers didn’t always see eye to eye. Against both McKean’s and Henderson’s advice, Dunlop refused to purchase enslaved workers in addition to those inherited with the estate, forcing them to rely on hired labour.

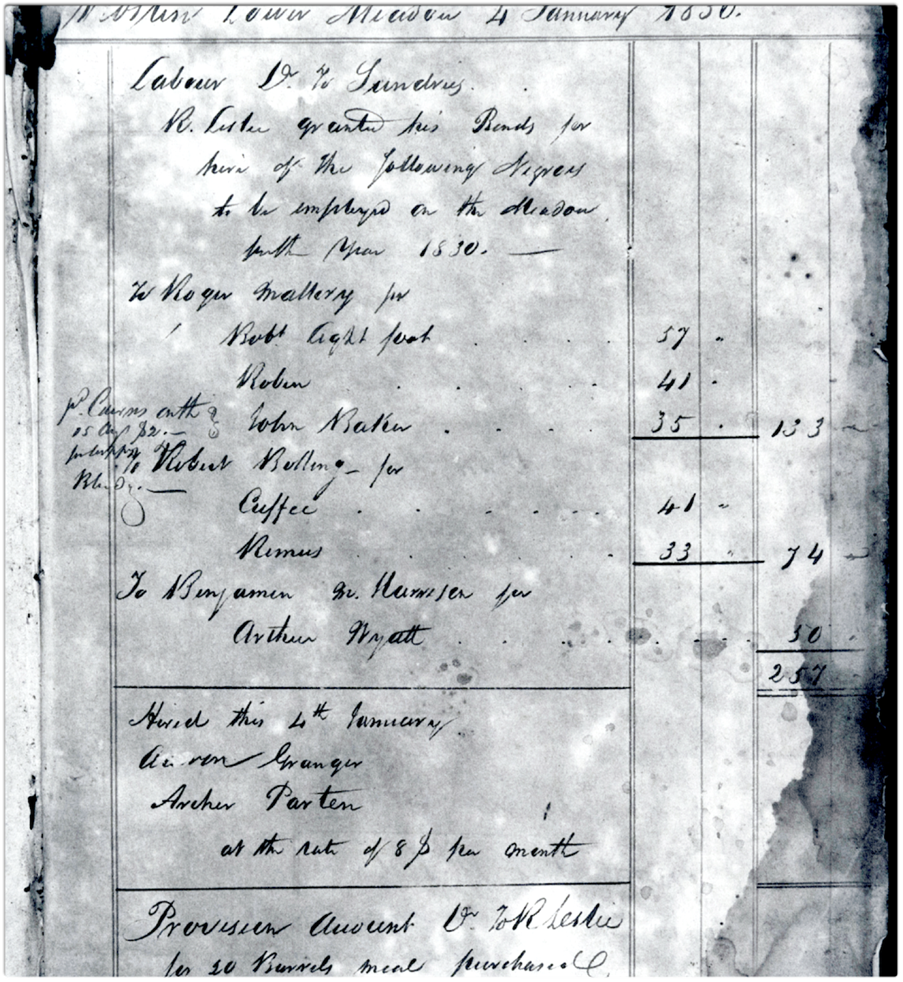

Charles Duncan formed Roslin Plantation from tracts of land he acquired in the 1770s-1790s. We have been able to identify the names of 80 individuals enslaved on the plantation over the period 1773-1831. At any one time, Roslin depended on the labour of between 37 and 44 such residents, to which some 20-25 enslaved labourers (mostly working men) rented ('hired') from neighbouring estates, on an annual or as-needed basis, were a substantial addition. The ledgers indicate that Roslin under McKean and Henderson relied heavily on such workers, who were instrumental in building new structures and clearing fresh land.

Being hired out in this way was very difficult for the individuals involved. Although temporary workers might try to influence where they would be sent, they were at the whim of their managers and owners, who had little motive to invest much in them. Hired hands might well clash with the permanent residents. This was the case at Roslin, where McKean described the ‘jealousy’ between the two. Contention largely stemmed from the constraint on resources and space, as well as disruptions to community and familial relations. But hiring remained part of the fabric of life at Roslin, with constant turnover meaning that relationships were continually made and broken. Both the forced movement and their experience of being imposed on the existing communities of African Americans to which they were dispatched meant that hired people struggled to maintain social connectedness. In this way, hiring could be, in itself, cruelly felt.

Ledger entry showing payments made for workers ‘hired’ from other plantations, written by William Henderson, 4 January 1830. The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia (LVA), Accession 23873, part 1.

Life under paternalism

The mix of men and women residing permanently at Roslin was relatively equal. In McKean’s time, Roslin seems to have had a significant elderly population, his letters referring on several occasions to a group of older men. Dunlop’s reluctance to add to the enslaved residents echoes his expressed anticipation of emancipating those he owned.2 Dunlop’s managers displayed a paternalistic approach in their correspondence, McKean calling the enslaved workforce ‘the People’. We catch glimpses of the workforce through what we have learned of plantation routines.

In periods when there was less to do in the fields, labourers maintained farming equipment and made improvements on the land. On Roslin, these improvements might take the form of draining swampland by digging extensive ditch systems or clearing meadow and forest to make the terrain suitable for arable crops. The number of axes purchased by the estate suggests that there were tens of labourers, included hired hands, working on these projects at any given time. McKean was keen on improving not only Roslin’s land holdings, but also the infrastructure and accommodation on the estate. To this end, people tore down and rebuilt their own quarters, as well as barns and storehouses.

The Roslin ledgers indicate that cornmeal and bacon were bought regularly to distribute among the enslaved population, with the occasional addition of pickled mackerel. Whiskey was also included in the rations. During leaner times, just cornmeal is recorded as being ordered. The estate also adopted the common practice of having people produce a significant amount of their own foodstuffs. Roslin’s extensive kitchen garden would have supplied the ‘big house’, as well as others on the plantation, but it was also common to allow individual families small plots of land for growing vegetables and herbs. Provided it was in their own time, enslaved people were generally able to supplement their diets, and there were fish to be had from the nearby Appomattox River.

List of clothing for the enslaved population of Roslin, sent by William McKean to James Dunlop, 17 July 1810. The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia (LVA), Accession 23873, part 2.

Clothing held profound significance for the enslaved, as we know from subsequent interviews of formerly enslaved persons elsewhere, which often mention it at length. In Virginia, the most common fabric for garment-making was osnaburg, a textile woven from flax and hemp, used at Roslin before it was largely replaced by wool produced on the plantation. ‘The People’ manufactured their own outfits according to the patterns provided to them. Other textile goods such as cold-weather clothing and blankets seem to have been distributed once a year or once every other year. In August 1816, McKean noted that he had entirely forgotten this was the year people ought to have a blanket each and was worried the articles would not come in time for the incoming cold weather. People complained when managers only gave out second-hand clothing or supplies for mending in lieu of new garments. This occurred on Roslin during leaner times, as Henderson records. Enslavers also used clothing (selectively) to show favour and invoke loyalty, as for instance when Nancy Dunlop distributed red handkerchiefs.

Glimpses of another life

Something else is glimpsed through these papers. When Betty Wood (see Girton Reflects no. 7) referred to what the enslaved men and women of the Georgia Lowcountry held most dear, it was to speak of their families. The names that come across for the enslaved population at Roslin almost certainly include names bestowed upon them by their oppressors, those of children born on plantations being typically chosen or approved by the owners or managers. Moreover, it is not known if the spousal and parental relationships listed in the historical record indicate the volitions of enslaved individuals or if they too were imposed. With these caveats, we introduce some individuals and their relations.

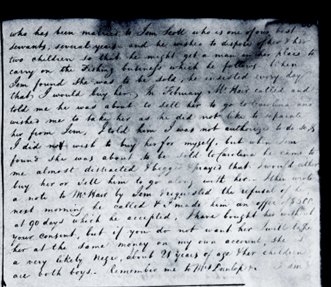

Jem Scott, described by McKean as among their ‘best servants’, was married to a woman on a neighbouring plantation belonging to a Mr Hair. The couple had two sons. Sometime in late 1811, Hair mentioned to McKean that he intended to sell Jem’s wife and children in order to replace her with a man capable of taking on his fishing business. This was made known to both Jem and his wife, from which point — on a daily basis — Jem began to petition McKean to purchase his family. The two white men noted that it was a shame to separate the family and Hair offered to sell Jem’s wife and children to McKean, who replied that he was not authorized to purchase anyone without Dunlop’s permission, nor was he interested in purchasing them for himself.

In early 1812, Hair declared his intent to sell Jem’s family to a slave trader going South. This would have been exceedingly alarming, as such traders were renowned as particularly brutal, a prospect considered the more frightening because of the uncertainty of where one might end up. Not only was there the danger of being purchased by a cruel or poor enslaver — people feared poor enslavers for demanding more while being less able to supply provisions — but also of the arduous nature of the prolonged forced march. Young women had to contemplate small children being discarded on the way. As Jem’s wife was 21, it can be assumed that her two children were very young at the time.

McKean describes the exchange between himself and Jem after discovering this news: ‘Jem found she was about to be sold to Carolina he came to me almost distracted & begged & prayed that I would either buy her or sell him to go along with her’.3 Noting the wife’s age, and that both her children were sons (indicating successful procreation and the usefulness of male children for farm labour), McKean wrote to Dunlop that he had made an offer for the woman and her children. He apologized to Dunlop for purchasing enslaved persons for Roslin without his permission, and offered to take it out of his own salary if Dunlop disagreed with the purchase. Evidently Dunlop agreed and kept her and her children as property of the estate. The manager paid in the region of $500 over a period of 90 days.

Extract from a letter from William McKean to James Dunlop, 4 April 1812. The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia, Accession 23873, part 2.

At the other end of the age spectrum were the Browns, an elderly couple. Unfortunately, the remarkable Mrs Brown’s first name is lost to time. Her husband was also named Jem. This transcription of a letter written to Dunlop by McKean in 1816 tells part of the story.4

I entirely forgot to mention to you … that I had sold Jem Brown to his wife, he has not lived at home since I took the management indeed he would have been but of little service if he had lived here. I had no intention of selling him, but they were after me every day & at last I told them that I would take what he was valued at for him which was $300 & she agreed to give it. She paid me $250 in silver which I sold at 5 per cent premium & the Balance she paid in paper money — she has now employed a Lawyer to endeavour to obtain his freedom, which I told her was great folly, because if she succeeded in obtaining his freedom, he could not enjoy it but a few years, she said she did not mind, her wish was that he should die free. . . . I was somewhat premature in disposing of Jem Brown without your approbation, but I did not think at the time I made the offer that she was able or would be willing to give that price for him.

Reflection

People become present for us as individuals when we encounter their names, yet they are also enmeshed in relations of all kinds, not least of kinship. After all, the Dunlop couple had acquired their landed interests from Mrs Dunlop’s parents and grandparents. Tracing connections is the easier for the managerial (and legal) accounting by which track is kept of property holding. However, if it is as property that enslaved people are named in many of the records, this ‘individualization’ of their presence could also work against the flourishing of the kinds of connections they might indeed have held dear, as we have seen in hiring practices. The general absence from the records of people’s manifold relationships gives a special charge to those moments that notice them.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: January 2024)

Coming Next: No. 9, March 2024

Following the money

In 1885, Girton College received news of an unexpected legacy that included money, stocks and securities, and personal effects such as books, lace, and a rich wardrobe (see Girton Reflects no. 1). In 2020, the College set out to trace the complex pre-history of the money and assets in the Gamble bequest.

Citations

- The Roslin Estate papers as held in the Library of Virginia. It has not yet been possible to do more than note further, possibly more extensive estate papers in other holdings (such as the Virginia Museum of History and Culture).

- James Dunlop’s will specifies that all enslaved persons working at Roslin – purchased or inherited – should be released from bondage after his death (he also intended to emancipate certain purchased individuals in his lifetime, but our information is as yet uncertain as to whether this happened).

- Letter from William McKean to James Dunlop, 4 April 1812, The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia, Accession 23873, part 2.

- Letter from William McKean to James Dunlop, 28 August 1816, The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia, Accession 23873, part 2.