The abolitionist cause among Girton’s founders and supporters

Published: August 2023

When the Working Group began to inquire into the possible legacies of enslavement at Girton, it knew that among its founders and early supporters -- those who helped form the idea of a women’s college -- were advocates for the abolitionist cause. Pro-slavery arguments of the time promoted the so-called ‘civilizing’ effects of regimented labour, just as plantation owners in Virginia might uphold paternalism and patriarchy as a virtuous form of control (see Girton Reflects no. 4). Abolition, by contrast, was about freedom from the controls by which the enslaved were treated as less than adults and less than persons. That did not imply that abolitionists were themselves free from all the prejudices of their times, as the Cambridge University Report on Legacies of Enslavement lays out. But it did lead them to develop views about human flourishing to which we respond today.

We turn to one aspect of these anti-slavery commitments, namely the part they appear to have played in perceptions of what emancipatory politics was about and how it might be organized. What did that entail in practice?

Consider four women who were particularly close to Girton’s leading founder, Emily Davies: Barbara Bodichon, Anna Richardson, Charlotte Manning and Emelia Russell Gurney. Their families all had a significant involvement in abolitionism, at some moments right at the centre. These women in Davies’s circle were concerned both about the situation of enslaved people overseas and the plight of women at home, including married women, whom they regarded as also in need of emancipation. For all the differences in material circumstance, at the time the two situations were frequently juxtaposed as direct parallels.

Photograph of Emily Davies, taken by an unknown photographer, circa 1870 (archive reference: GCPH 5/4/9pt).

Campaigns and campaigners

Many of those born around 1830, and growing up to form the first generation of largely middle-class women with a high profile in the British public world in the 1860s, will have seen or heard of their mothers', grandmothers' and other female relatives' involvement in efforts to abolish slavery earlier in the century. It had been campaigning against enslavement which led to the first mass petitioning of parliament by women in the 1830s; and it was out of this movement that the first national pressure groups with a separate female membership were formed in the 1850s.

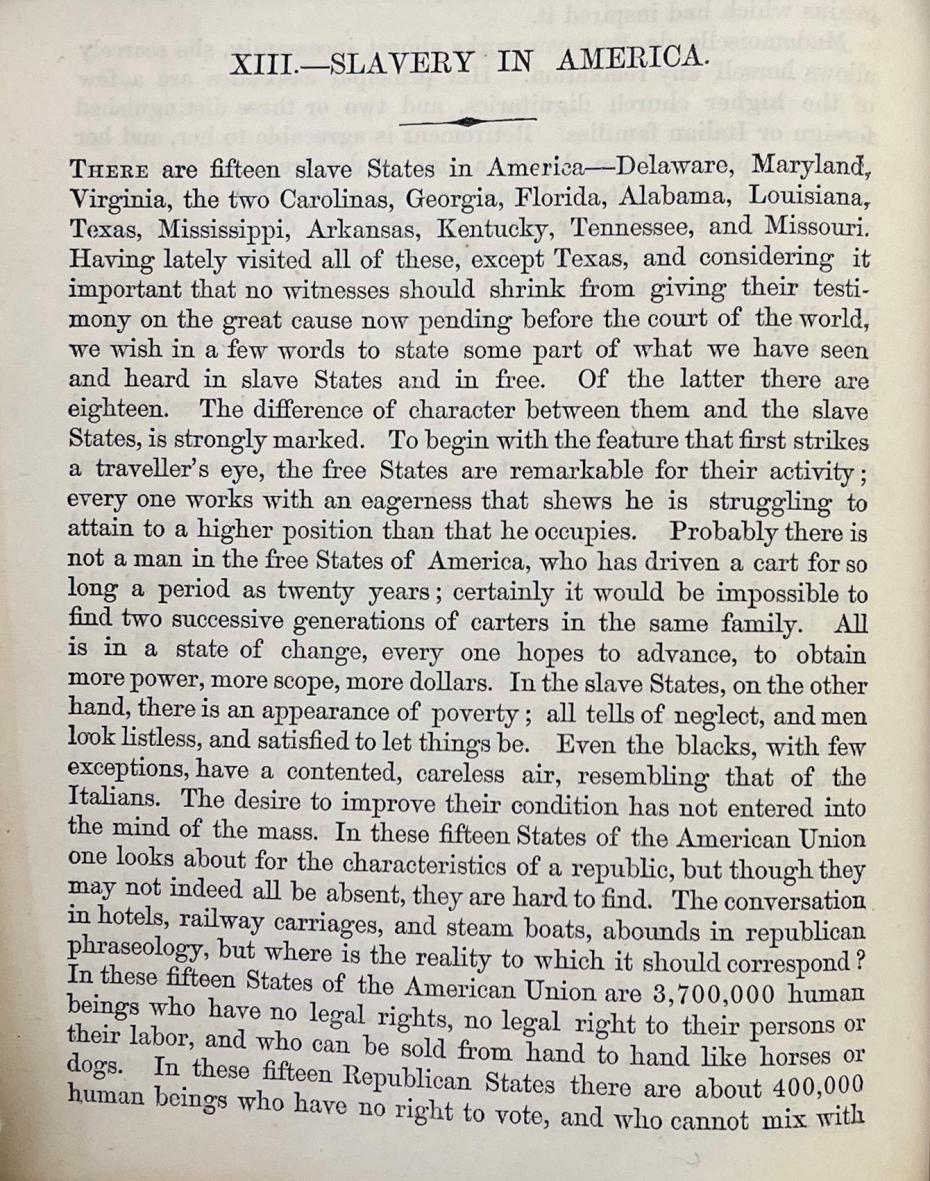

This broader story was borne out within the close circle of women that Emily Davies formed around herself as she began to organize, from the mid-1860s, for the establishment of a College for Women. One of her closest colleagues and effective partner in the foundation of Girton, Barbara Bodichon, came from a Radical family in which both the women and the men were active anti-slavery campaigners. When Bodichon went with her new husband for a working honeymoon to the United States in the late 1850s, she tried to find out about the practices of enslavement and the life prospects for those who had been individually emancipated from it. On her return she wrote a number of highly informative and critical articles on the situation of enslaved and freed women and men around New Orleans in Louisiana. Here is an extract (as mentioned in Girton Reflects no. 3, her writings do not escape the racialized expressions of her age).

First page of ‘Slavery in America’, an article by Barbara Bodichon which appeared in The English Woman’s Journal, Volume II, October 1888 (special collections reference: BodichonX 087077). This was one of several articles written by Barbara Bodichon based on her travels in the United States in 1857–58. Her letters and journal from that time were published in 1972 as An American Diary, 1857–58.

Nor was her endeavour unique, for Davies’s close circle also included others of like mind. Anna Richardson came from one of the dominant Quaker families in the North East of England, most of whom were involved in regional and national anti-slavery campaigns throughout the early nineteenth century. There was Charlotte Manning, who had encouraged her younger brother to get involved in abolitionism and attend what became a famous event, the World Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840. Another striking example was Emelia Russell Gurney, whose male ancestors on her mother’s side had played key roles in the drafting of the legislation both to abolish the slave trade in 1807 and to abolish the ownership of the enslaved on British territory in 1833.

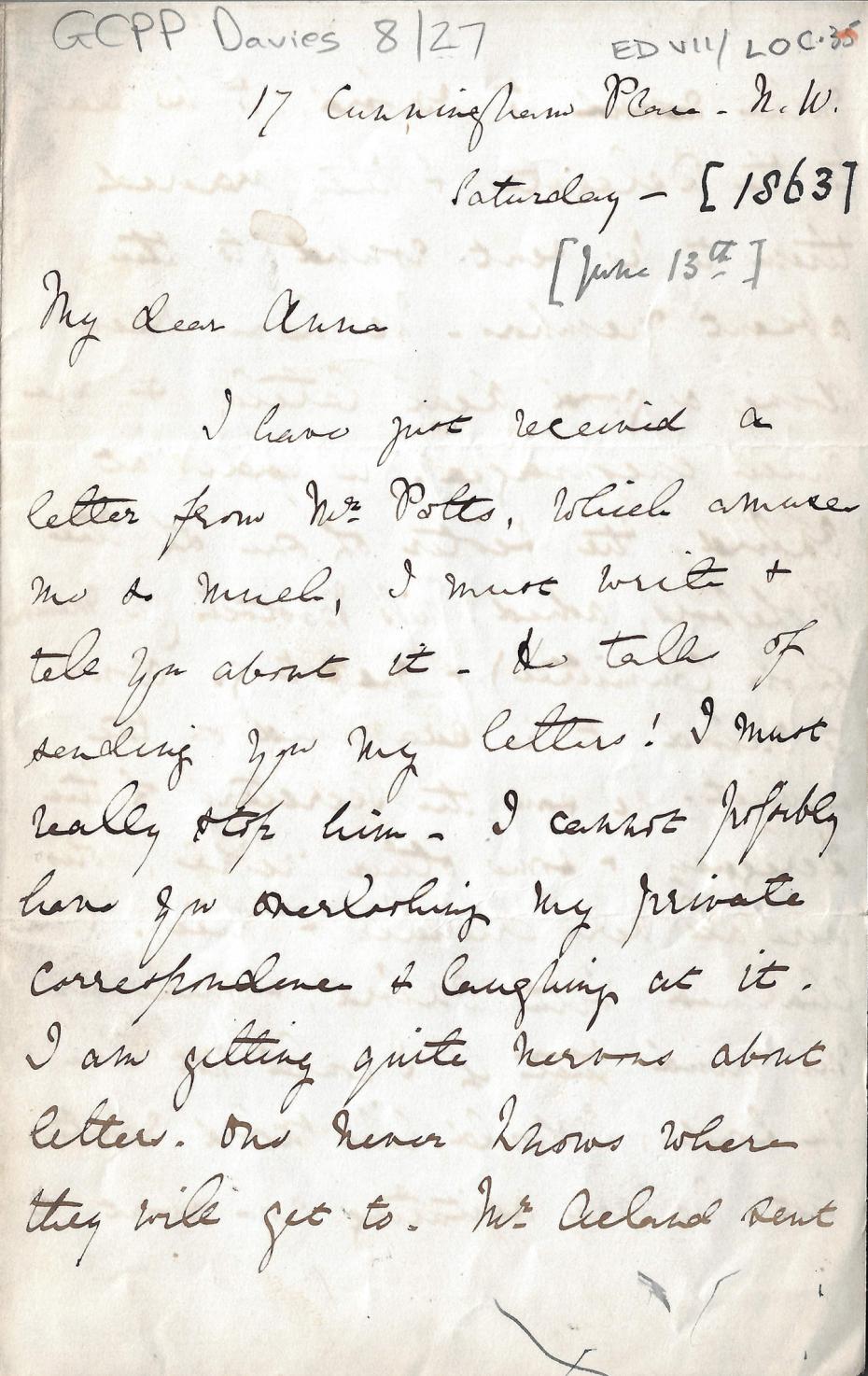

Letter from Emily Davies to Anna Richardson, 13 June 1863 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 8/27pt). Anna and Emily had become friends as young women. This letter is from a time when both were campaigning for girls to be allowed to sit the new ‘Cambridge Locals’ (end of school exams then open only to boys). ‘Mr Potts’ is Robert Potts, in 1863, Secretary of the Cambridge Syndicate which administered the Locals.

It is significant that Emily Davies should have found herself with associates who were not only determined to increase the opportunities available to themselves and women generally, but who had also been exposed to anti-slavery campaigning within their own families. Indeed, from the perspective of the propertied middle classes, it became almost habitual for them to compare enslavement to the constraints endured by women, especially when it came to married women’s legal standing. Not only did women’s property pass to their husband on marriage, a woman had neither legal recourse to the custody of their children nor legal redress from cruelty or negligence.

In her pioneering petition of 1855 for the protection of married women’s property rights, Bodichon argued:

it is time that legal protection be thrown over the produce of their labour and that in entering the state of marriage, they no longer pass from freedom into the condition of the slave, all whose earnings belong to his master and not to himself.1

A revival of concerns

All the same, this might just have remained something in the deep background of the first women’s movement. Abolitionist activity had died down considerably by the middle of the nineteenth century as, in the public mind, the issues for which Britain had direct responsibility seemed to have been resolved. For the ending first of the British slave trade and then of enslavement on British territory made it appear as if the abolitionist movement had achieved its major aims. However, the American Civil War brought abolitionist issues back to the centre of public life.

Picture of a crowd of people gathering to greet Garibaldi in London, from The Illustrated London News, 23rd April 1864 (reference The Illustrated London News, no. 1256, p. 397).

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, coming into force early in 1863, made it clear that the enslavement of Black people in the Southern states was the key issue in the American Civil War, and sparked off a major wave of emancipationist and wider democratic aspiration throughout the Atlantic world. In Britain, the turning point was a visit of the republican nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1864. This turned into a spectacular outbreak of progressive enthusiasm and led the government to curtail his visit for fear of too much unrest spreading in the North of England and the West of Scotland. But this only further fuelled Radical agitation, leading to a hugely popular campaign for the extension of the vote to more adult men, the Second Reform Act of 1867 and the election of the first reforming Liberal government the following year.

The point of all this for Girton is that these campaigns sparked off a closely linked chain of events with Emily Davies at or near the centre of them all -- beginning with a national women’s anti-slavery organization and leading to the first public campaign for votes for women.

Photograph of Charlotte Manning, taken by an unknown photographer, circa 1860 (archive reference: GCPH 5/1/1). In October 1869, Charlotte Manning would become the first Mistress of the new College for Women, later re-named Girton College.

For Emily Davies and her close colleagues were making the case for women at the core of every phase of these developments. Davies and Manning were both on the executive committee of the Ladies’ London Emancipation Society, set up in the spring of 1863 as an immediate response to Lincoln’s Proclamation. One outcome of this campaign was that Davies was part of a group that presented welcoming addresses to Garibaldi in London the following year. Davies and Manning then instigated a national discussion group for general women’s issues, which became known as the Kensington Society, after Manning’s home in that part of London spacious enough for its large meetings. And the major outcome of this initiative turned out to be a new campaign, initiated by Bodichon. The intention was to organize support for John Stuart Mill in his bid for a seat in parliament on a platform of votes for women in 1865, to be followed by a major national petition to back that up once he had been successfully elected. Before long, as Bodichon was increasingly ill or abroad in Algiers, Davies took on the leading organizing role in this national campaign for women’s suffrage.

It did not get very far. Davies was pleased that Mill had been able to make the first serious speech about the issue in parliament during the passing of the Second Reform Bill, but once that favourable moment was over, she went back to focusing on her main special interest: improving educational opportunities for women.

More than a single campaign

At this point our story can join the one long familiar in the annals of Girton’s history, that of the hard work and financial burdens that Davies and Bodichon undertook in order to set up in 1869 what quite soon became Girton College. But we can see now that there was a wider, external context to the founding of the College.

![List of members of the General Committee and the Executive Committee, from the College [Annual] Report, November 1869 (archive reference: GCCP 1/1/1pt).](/sites/default/files/styles/930_scale/public/images/GCPP1-1-1pt-AnnualReportNov1869-ExecutiveAndGeneralCommittee-colour600dpi.jpg?itok=Rn7Qj1-w)

List of members of the General Committee and the Executive Committee, from the College [Annual] Report, November 1869 (archive reference: GCCP 1/1/1pt). Here, among the names of people very closely associated with the young College and alongside Miss (Emily) Davies are: Mrs (Barbara) Bodichon, Mrs (Emelia) Russell Gurney, and Mrs (Charlotte) Manning.

On the one hand, quite apart from the more or less direct benefits that College gained from overseas enslavement, the Atlantic slave trade and forced plantation labour in the Caribbean and the American South was so integral to the whole British economy in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that nobody in this country was not implicated to some degree. On the other hand, the main figures in the group of women who founded Girton became used to campaigning not only for themselves but also for others. They had come from families that had boycotted goods produced by enslaved people and campaigned for the abolition of slavery for many decades, a project in which their older female relatives had played active roles. More immediately, the wider wave of democratic enthusiasm that (we surmise) floated the foundation of the College in 1869 can be seen as part of an international response to abolition as the central issue in the American Civil War. And no doubt one reason that those events had such an impact lay in the way in which the campaigns for the abolition of enslavement and for the improvement of women’s lot in Britain had been closely intertwined for two to three generations.

Emily Davies wrote to Barbara Bodichon in 1862: ‘If we exist for anything, surely it is to fight against slavery’; she was referring to that of women, whether overseas or at home. 2

Reflection

Aware as historians are these days of the problematic side of the British moves to abolition – the failure to pursue continuing injustices; compensation for the enslavers where the enslaved had none – such moves were highly instructive for those pursuing the emancipation of women. In the middle of the nineteenth century, what we might regard as an early generation of British feminists were re-living what some of them will have seen in the way women of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations advocated abolition. In campaigning for themselves, they were also campaigning for others. This dual engagement also appears, we may imagine, to have contributed both to the skills and to the spirit that carried their vision for women’s education.

Coming next: No.6, September 2023

An intriguing image

A group portrait, a religious conference and the encounter between a Black American preacher and one of Girton's early supporters.

Citations:

- The full text may be found in Hester Burton, 1949, Barbara Bodichon, 1827-1891. London: John Murray, pp. 70-71.

- BB to ED 3 December 1862. Emily Davies, 2004, Collected letters, 1861-1875, edited by Ann B Murphy, Jerome J McGann, Deidre Raftery and Herbert F Tucker. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, p.9.