Alfred Waterhouse and family

Published: July 2024

The Waterhouses have already come into our narratives (see Girton Reflects no. 3) through Gertrude Gwendolen Crewdson. Her mother was from the same family as the College’s famous architect, Alfred Waterhouse, Gertrude’s uncle. A double connection for Girton. Three generations of Waterhouse men tell us something of their deep roots in the practice and spread of enslavement. This particular story points both to the compounding of British generational wealth and to a family’s social entanglement with networks of enslavers or more generally with those whose interests exploited the riches gained from enslaved labour. In one sense, Girton College’s own legacies of enslavement can be likened to those of its architect. College and architect at once established their reputations in post-abolition Britain and were also the beneficiaries of, and in complex ways shaped by, such labour.

From Nicholas Waterhouse & Co to Nicholas Waterhouse & Sons

Nicholas Waterhouse (1768–1823) was born in Manchester as a member of the merchant class. After an apprenticeship with a fustian manufacturer in Bolton and a further stint working in a cotton warehouse in Manchester, Nicholas established himself in Liverpool. In 1790 he opened the firm Nicholas Waterhouse and Co., specialising in cotton, which was emerging as ‘the most crucial of early industrial commodities’.1 Nicholas’ timing was fortuitous. The pace of industrialisation and expansion of textile manufacture in the North West of England meant that, in the late eighteenth century, Liverpool was overtaking London as the centre of Britain’s cotton imports. In that period, most raw cotton entering Britain through Liverpool came from the West Indies and Brazil. Nicholas Waterhouse & Co was described as the third most important Liverpool importer of cotton from Guyana between 1796 and 1815. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, these sources were shifting to the American South, following the expansion of cotton growing into the Mississippi River Valley.

The Liverpool Cotton Exchange, 1893. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-stereo-1s22375. From 1808, the Liverpool Cotton Exchange operated in the courtyard pictured here, close to the Town Hall. In 1896 it moved to indoor premises, and in 1906 a new building was commissioned which was only replaced in the mid-1960s. Before 1808, cotton exchange business took place largely on the city’s Castle Street.

Nicholas fashioned himself into a professional cotton broker — a new role in this area of ever-growing commerce at a time when there was very little precedence — which gave him a significant influence in the development of the Liverpool market.2 Nicholas is often cited as one of the central figures in the British cotton business (the company's papers have been the foundation of studies into the economic development of the North West). All in all, around 1800 his firm was handling some 30% of the cotton passing through Liverpool. Alongside his involvement in the cotton trade, from 1800 onwards Nicholas was a partner in the firm of Waterhouse & Sill, which imported coffee, sugar and wine, primarily from Demerara.

In addition to his investments in the cotton trade and adjacent markets, Nicholas Waterhouse facilitated the spread of enslavement in other concrete ways. Alongside other partners, he subsequently brought into the business three of his eight sons, Rogers, Daniel and Alfred, who all had interests in plantations in British Guiana, as Guyana was then called, and the firm became Nicholas Waterhouse & Sons. Additionally, at least four of Nicholas’ former apprentices became established cotton brokers themselves. Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, as a broker Nicholas was integral to the establishment of a system of credit for merchant importers and exporters in Liverpool. In his economic history of American enslavement, Edward Baptist describes credit granted on easy terms between white men as foundational to the spread, efficiency and brutality of the transatlantic enslavement that was feeding early nineteenth-century efforts to increase cotton production. Credit permitted the establishment of plantations, the acquisition of land on a large scale, and the purchase of groups of people on speculation.3

‘Slaves shipping cotton by torch-light, River Alabama’, Engraving, 1842. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, LC-USZ62-31030.

At his death in 1823 Nicholas Waterhouse’s net worth was £100,000, which was largely re-invested back into Nicholas Waterhouse & Sons.4 In addition to building his business, Nicholas and his wife, Ann, devout Quakers, were generous benefactors in Lancashire, providing for example the funding necessary to open the Lancashire County Refuge for the Destitute. The firm Nicholas had founded continued to operate until the retirement of partner Thomas Bouch in 1875.

Alfred Waterhouse Senior, Man of Leisure

Nicholas’s son, Alfred (1798-1873), was raised to follow in his father’s footsteps, entering the family business as a young man. However, in 1843 at age 45, he retired prematurely as a partner. Married to the effusive Quaker preacher and diarist, Mary Bevan, Alfred spent the rest of his life as a so-called gentleman of leisure. The public reason given for his departure from the business was that the ‘competence [of the firm] was secured’ in the hands of his brothers and that he was eager to lead a more pious life -- one focused on ‘the welfare of the soul’ instead of one ‘spent in amassing more than enough’. However, his wife’s journal claimed the reason for his ‘unhappiness in the business’ was an aversion to the firm’s involvement in the sale of rum, ‘after the West Indian planters changed from cotton to sugar production’.5 The issue of enslavement is not discussed in Mary’s writings, nor does there seem to be any recorded commentary on this subject from Alfred himself. The couple continued, however, to draw an income through the family firm as well as through investments in other endeavours. In 1835-36 Alfred, alongside his brothers, had been part of two unsuccessful compensation claims related to enslaved workers on properties in Guyana: Plantations John Cove and Craig Miln (296 enslaved) and Clonbrock (364 enslaved).

Although Mary claimed the family had a curtailed income after her husband resigned his partnership, her writings also indicate they continued to live well, and we know that they employed at least three servants. The couple moved in abolitionist and free-labour circles –- including the Crewdsons (mentioned at the beginning) and the Richardsons (Girton Reflects no. 5) -- while maintaining ties to the Waterhouse family and their affiliated social sphere. Alfred Waterhouse Sr. died in 1873, leaving an estate valued at £70,000 (see n. 4).

Alfred Waterhouse Junior, Professional Architect

Born in secure luxury at Stone Hill in Liverpool, as a young man Alfred Waterhouse Jr. (1830-1905) aspired to become an artist. His parents, however, encouraged him to pursue a more stable and respectable vocation, which he found in architecture. Following his time at the Quaker Grove House School in Tottenham, and a nine-month continental tour, Alfred began architectural studies in 1848 under Richard Lane, a professional in his grandfather’s home town of Manchester. Under Lane’s auspices, his earliest designs were for his father’s house at Sneyd Park, close to Bristol; for other family members, and for members of the Quaker community, among whom his family name held considerable sociocultural currency. According to Alfred’s biographers, the foundations of his career can be found in ‘the strong Quaker presence in the business circle in the north. He was fortunate that by mid-century these wealthy magnates were beginning to forsake the extreme simplicity of the old Quakers and to set themselves up in mansions of solidarity and comfort’.6

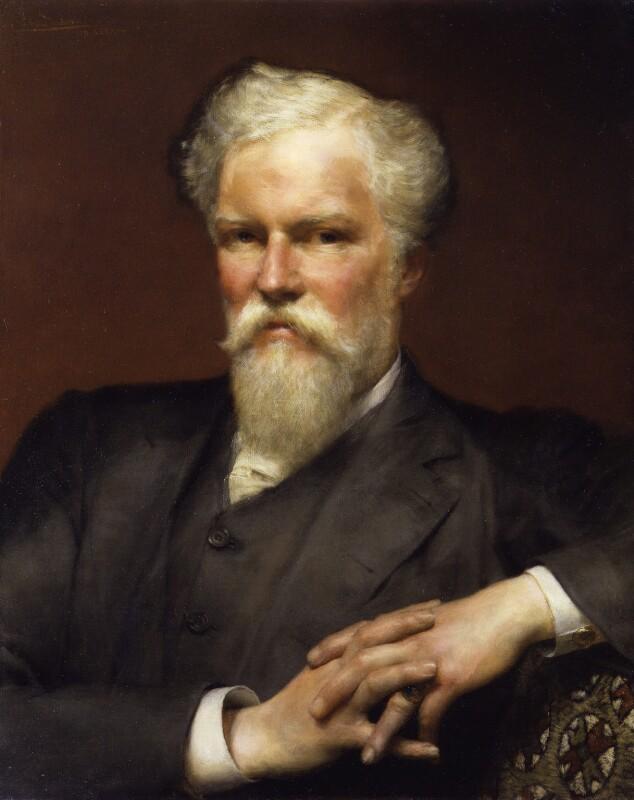

Alfred Waterhouse by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1891, held in the National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 6213. This is licenced under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Relatively early in his career the architect gained the important patronage of Roundell Palmer, later Lord Selborne. This provided him not only with substantial work, but also with an entrée into even more elite and aristocratic circles. In 1869, Alfred refurbished and made significant additions to Selborne’s Hampshire mansion, Blackmoor House. The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery (University College London) lists Selborne as an immediate descendant of a claimant or otherwise a beneficiary of compensation for enslaved people freed in the 1830s. The Palmer family were landowners throughout the British slave colonies and had connections to the East India Company. Roundell’s father, William Jocelyn Palmer, operated and claimed compensation for extensive landholdings -- the Springs and Mount Aire Estates -- in Grenada.

Selborne was not the only known enslaver who would figure among the clients of the architect over the course of his career. While we do not have evidence of Alfred’s personal beliefs on the subject, it seems that, throughout his life, he fostered social and professional connections on both sides of the issue of enslavement. Even his biographers lament Alfred’s ‘intensely private’ nature concerning his relationships, family life and personal opinions. Politically, it seems, he had Liberal leanings, while maintaining social and professional connections among the Liverpool Tories. Alfred, like many others of his generation, had been raised and shaped in a disparate milieu — one that included his parents’ involvement in free-labour and abolition, as well as the large-looming legacy of his grandfather, Nicholas.

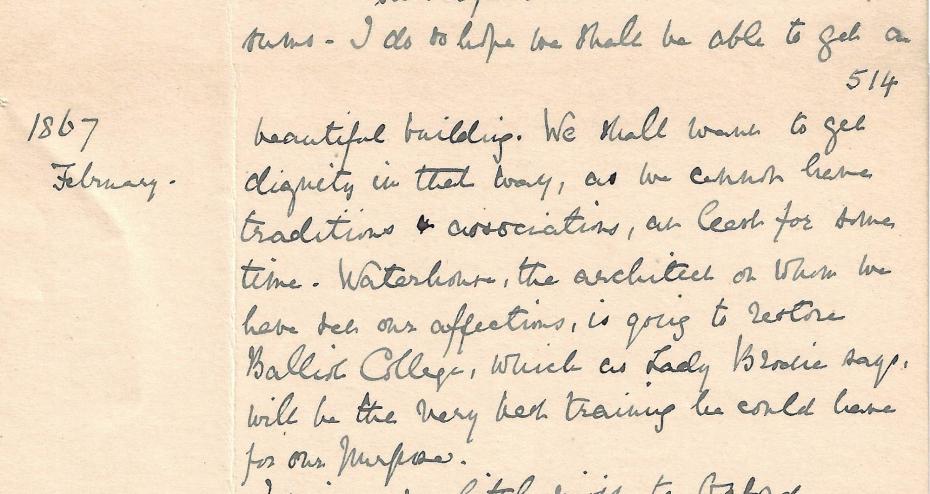

Extract from Emily Davies, ‘Family Chronicle’, quoting a letter she wrote to her friend Anna Richardson naming Alfred Waterhouse as her desired architect for the proposed College, 4 February 1867 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 1/1pt, pp. 513-14).

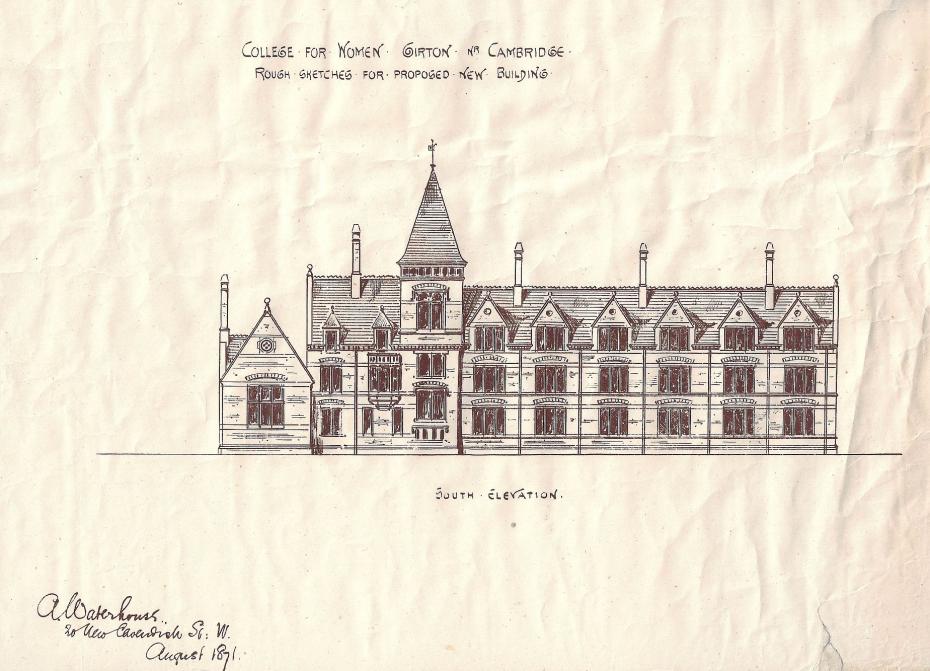

Sketch of the south elevation of Old Wing, signed by Alfred Waterhouse, August 1871 (archive reference: GCAR 2/3a/1/6/1/1pt).

Reflection

It is impossible to ignore the stamp that, at Emily Davies’ insistence as it were, the younger Alfred Waterhouse put on the character of Girton’s buildings. Nor should we ignore the fact that the College’s first and principal architect owed substantial opportunities in life to his family’s participation in the trade of an industrial commodity obtained through enslaved labour. Yet by then those once visible relations had more or less disappeared. The fortunes of these three generations of Waterhouse men must have been repeated many times over the nineteenth century: wealth made by industrialists seguing into the inheritance of descendants enabled to be other kinds of persons. In this case, behind that enablement lay another, trade in raw materials produced under particularly inhumane conditions. Nicholas’s business was conducted in a proximity to this process, one that was to become remote from the wealth passed on to successive generations of the family. His son seemingly anticipated this in his lifetime, whatever his reasons for turning away from commerce. For his grandson, the brutal realities of enslavement must have acquired as much a mix of connection and disconnection as coloured his knowledge of the grandfather he had never met.

Masthead image: Watercolour painting by Alfred Waterhouse of Girton College, 1887 (archive reference GCPH 3/2/27).

Coming Next: No. 12, September 2024

Past and future

The series concludes with reflection on the phases of Girton’s enquiries, and on what the future might bring.

Citations

- Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told, p. 82.

- In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Liverpool was a significant import hub for other New World products and was one of the largest points of entry of enslaved people in Britain. See Hyde, Parkinson and Marriner, Liverpool Slave Trade, pp. 368-369.

- Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told, pp. 90-91.

- £100,000 is approximately £5,750,000 in buying power today (National Archives database in 2017).

- The several quotations in this passage are from ‘an assessment of his life’ in the Quaker, Annual Monitor (1875), as found in Cunningham and Waterhouse, Alfred Waterhouse, p. 7.

- Cunningham and Waterhouse, Alfred Waterhouse, pp 3, 9.

References

Baptist, Edward, 2014. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, New York: Basic Books.

Cunningham, Colin and Prudence Waterhouse, 1992. Alfred Waterhouse 1830-1905: Biography of a Practice, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hyde, Frances E., Bradbury B. Parkinson and Sheila Marriner, 1953. ‘The Nature and Profitability of the Liverpool Slave Trade’, Economic History Review, 2.5, 368-377.

Further sources

On Nicholas Waterhouse’s Liverpool business, see Francis E. Hyde, Bradbury B. Parkinson, and Sheila Marriner, 1955, ‘The Cotton Broker and the Rise of the Liverpool Cotton Market’, The Economic History Review, 8.1, 75-83, and Susanne Seymour and Cassandra Gooptar, ‘The Arkwrights and Slavery: A Scoping Report’, produced for Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site (DVMWHS), University of Nottingham (July 2021). The works of Alfred Waterhouse the architect, not mentioned here beyond the early years, are considered in Nicholas Draper, 2019, ‘British Universities and Caribbean Slavery’, Social and Economic Studies, 68.3/4, Special Issue on Reparations, 127-146.