The College for Women and the Heiress

Published: April 2023

We open this series of reflections with the story of a woman drawn to leave funds for an institution founded for women’s education. The fact that Jane Catherine Gamble was of independent means is a tale in itself. This is an important beginning not just because her bequest was transformative for the growth of the College. Gamble’s story has also been transformative for how we might wish, in present times, and in a much larger sense, to consider the foundations on which Girton was built.

Through this one woman’s bequest Girton has acquired, in a very concrete and vivid sense, knowledge of the economics of enslaved labour and the intolerable conditions under which the primary producers of some of her wealth lived. We may have been aware of such matters in a general sense: this narrative connects College to specific people and their times. It also points to some of the complexities that Girton’s inquiry into the legacies of enslavement has raised.

The name comes from the University of Cambridge’s enquiry into a period of its history when it and its colleges benefited substantially from wealth known to have been generated under conditions of enslavement. The legacies of that period include racism and inequalities that have not gone away, which is why they are also a story for the present.

We have to understand that for much of the nineteenth century women’s prime sources of independent wealth came through marriage and inheritance, and inheritance immediately takes us back one or two generations. Raising money for such a radical initiative as a college for women turned out to be a painfully slow process, but the sizeable gifts of a small handful of women proved real turning points: the chances are that these reflected family wealth.

Out of the blue, in 1885, Girton learned of a bequest from the late Jane Catherine Gamble. Instantly pressed into service, the gift was transformative. The then unknown Gamble stood out from the circle of Girton’s early benefactors and supporters. She grew up in Virginia, but while still a girl moved to London, which became her home for the rest of her life. It did not take long to discover that the residuary estate Gamble left to Girton had been formed in her parents’ and grandparents’ generations in large part from plantations based on enslaved labour and from other enterprises that benefitted from the work of the enslaved.

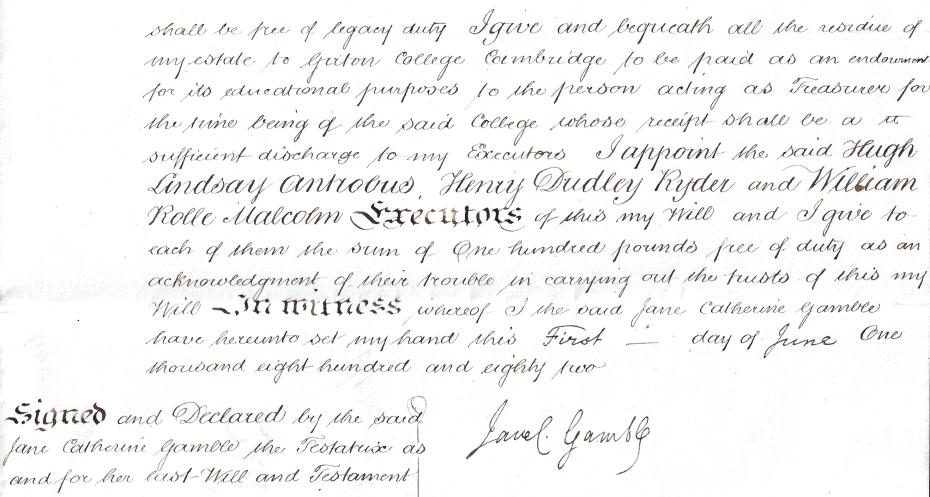

The Gamble Bequest

Excerpt from Jane Catherine Gamble’s will where she left the residue of her estate to Girton College, 1882 (archive reference: GCPP Gamble 2/20pt).

Jane Catherine Gamble was born in England in 1808 to parents visiting the UK from Virginia, USA. Her mother, Charlotte Gamble (née Duncan), died on the journey home, and Jane and her father, John Gamble, lived for the next few years with or close to her Gamble grandparents, near Richmond, Virginia. It seems her father’s 1813 re-marriage brought further disruption – before the age of 10 Jane had crossed the Atlantic once more to join the London household of her maternal aunt and uncle, Nancy and James Dunlop. That city became her home; she never returned to the USA.

The young Jane enjoyed a privileged life. Schooled at home, she learnt French and German, dancing and horse-riding. She read widely and precociously, and her aunt and uncle, leading artistic patrons, introduced her to renowned artists and writers of the day. Once launched in society, she frequently attended the theatre, formal balls, dinners and soirées. In 1838, she sat for her portrait by Alfred Chalon, a leading artist of the day who had just completed a celebrated painting of the young Queen Victoria in her State robes.

Portrait of Jane Catherine Gamble by A E Chalon, 1838 (archive reference: GCPH 4/4/2).

Jane travelled widely, first in Britain, then in Europe. In time she would become particularly entranced by Italy. She composed poetry and wrote plays and spent time with a wide circle of friends.

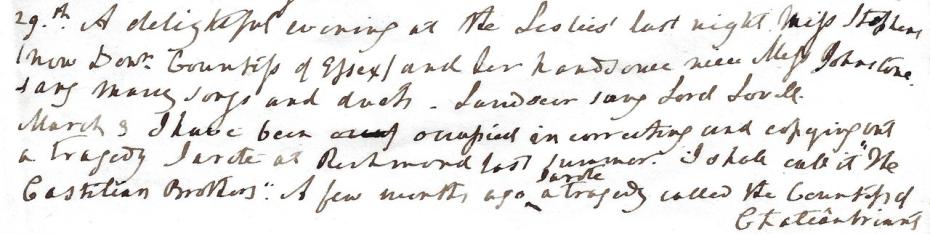

Extract of diary entries for February and March 1837, taken from ‘Fragments of a Life’, page 79, by Jane Catherine Gamble, circa 1876-1879 (GCPP Gamble 1/35pt).

Despite the appearance of ease and good fortune, however, Jane would later depict this life as one shadowed by sadness. The absence of a loving mother and the baleful influence of a stepmother were frequent themes.

Jane’s middle decades included great upset. By 1851, the successive deaths of her uncle, aunt, and their only child, had left her a substantial heiress. She became entangled with an American, Henry Wikoff. She rejected his marriage proposal, but events proceeded badly, and Jane found herself imprisoned overnight by Wikoff in a Genoese hotel room. A promise to marry brought escape; Jane courageously filed charges. At trial, avidly reported in American and British newspapers, Wikoff was found guilty of false imprisonment, and he spent 15 months in prison.

Afterwards, Jane’s life returned to its previous pattern – time in England spliced by European travel; periods of writing; visits with friends. She died in her beloved Florence in June 1885, aged 76. But perhaps those traumatic events over 30 years earlier influenced the institutions Jane thought she should support in her will.

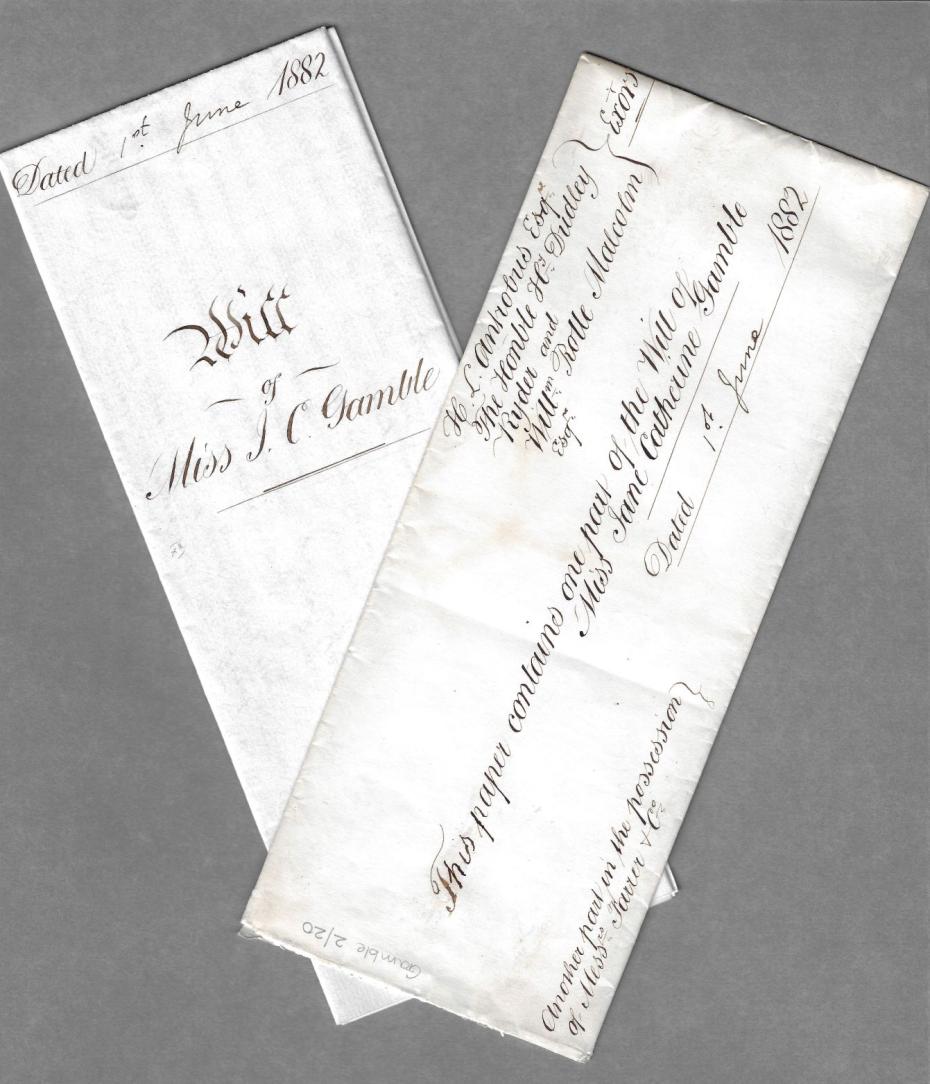

Jane Catherine Gamble’s will and the envelope it came in, 1882 (archive reference: GCPP Gamble 2/20).

The bequest

Later that summer, Girton College was surprised and delighted to learn it was Miss Gamble’s residuary legatee. It would eventually receive cash, artefacts, stocks and other securities valued at around £19,000 (worth around £2.6 million today). This news was considered a great boost to the College community: a mounting debt was reduced; new land was bought; and new buildings immediately planned to extend university-level education to further talented young women. Soon the confident red walls of Tower and Tower Wing could be seen rising on the Girton site.

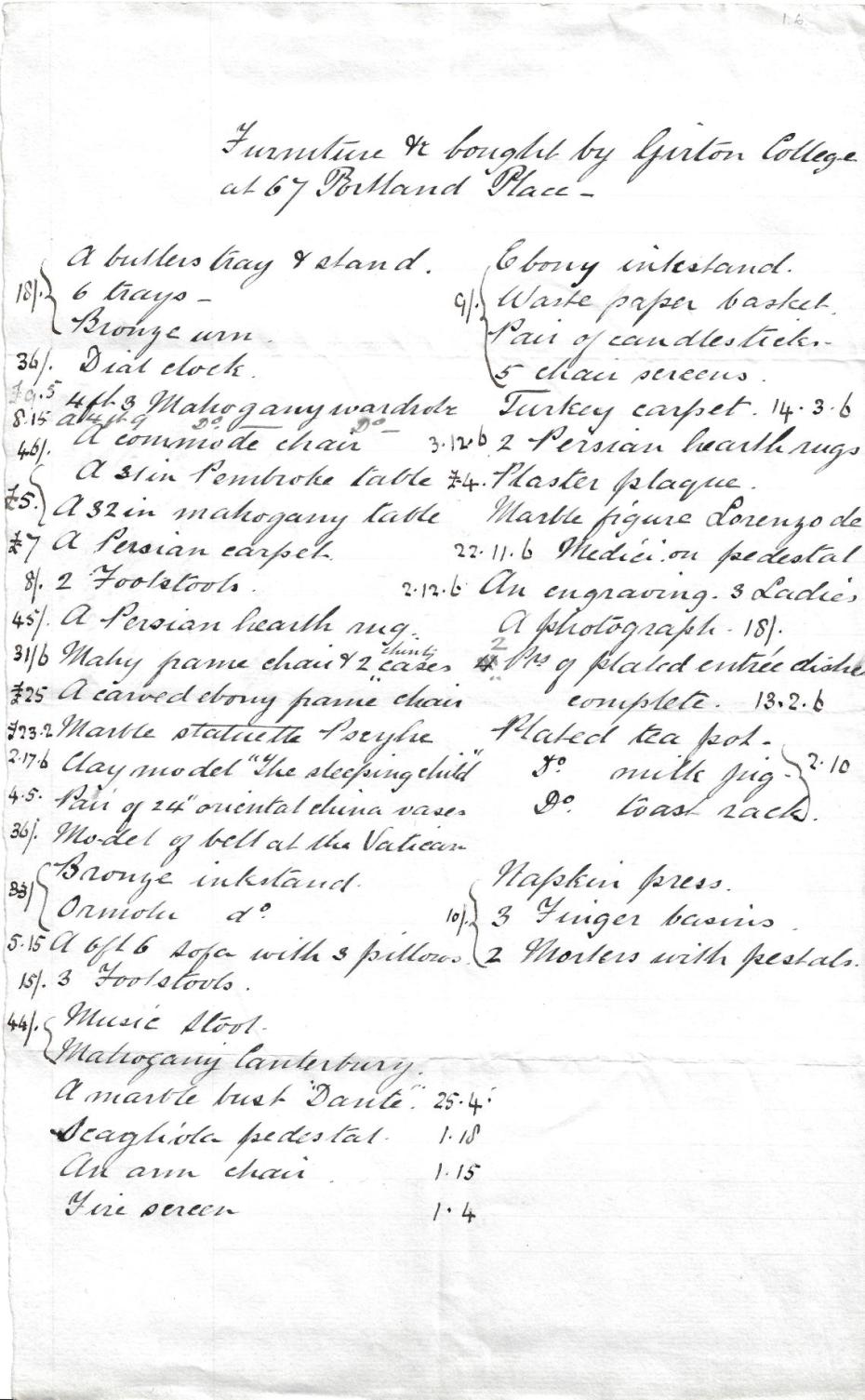

‘Furniture etc bought by Girton College at 67, Portland Place’ (Miss Gamble’s home) drawn up by Elgood & Son, 1885 (archive reference: GCAR 2/6/11pt).

It has proved challenging to uncover the origins of this unexpected bequest. Investigation has revealed complex and significant links to the horrific practices of enslavement and plantation production in the southern United States. We currently believe that Jane did not inherit from her father, John Gamble. While she lived with him (and with any enslaved domestic workers), he was not a plantation owner, although his personal wealth – and that of his parents – was built on participation in a Virginian economy dominated by enslaved production. After Jane left for London, however, John Gamble became an enslaver on a substantial scale and was also directly involved in the seizure of land from the indigenous populations of Florida. In later life Jane bemoaned her lack of paternal inheritance. After his death, and despite already being a wealthy woman, she took some initial steps towards making a legal claim to a portion of his estate. Although apparently unsuccessful, that she even considered such actions may make us pause.

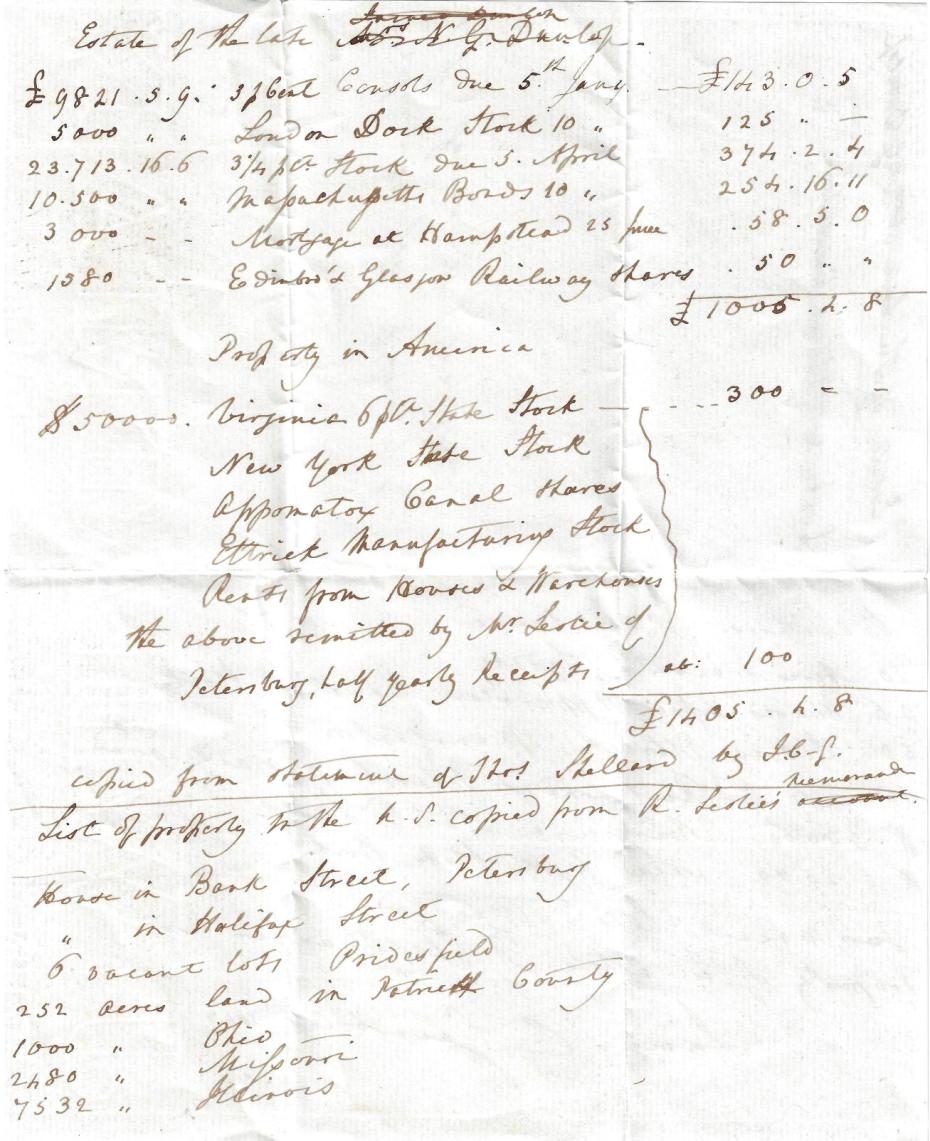

Rather than deriving from any Gamble inheritance, Jane’s adult wealth seems to have come entirely from her mother’s family, and especially from her maternal aunt Nancy, and Nancy’s husband, James Dunlop. That couple supported Jane’s comfortable lifestyle until their deaths in the 1840s. In 1847, Nancy, the last to die, left Jane an annuity of £200 a year; a lifetime right to live in the family’s elegant London home; and £10,000 in ‘consolidated Bank Annuities’. Those ‘annuities’ appear to have included a sizeable number of ‘Virginia State Stocks’, some of which (much decreased in value following the American Civil War 1861–1865), were passed to Girton in the 1880s. In 1851, Jane’s wealth grew further. The death of the Dunlops’ only child left her the sole beneficiary until her death of a Trust established by Nancy in her will. It was the remaining surplus from Jane’s 1847 inheritance, and from her income from that Trust that formed the bequest communicated to Girton in 1885.

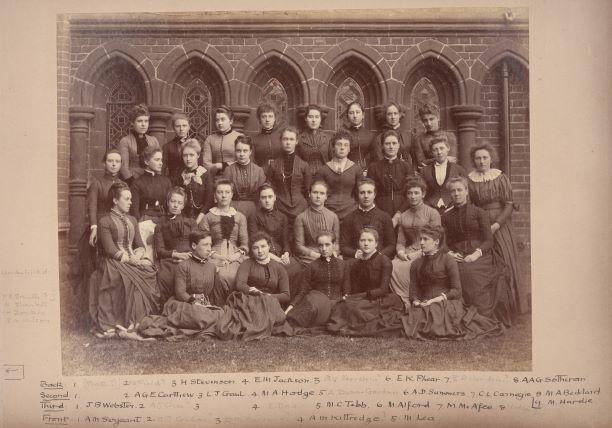

First Year photograph by an unknown photographer, 1887 (archive reference: GCPH 10/1/28). By 1887 total student numbers had increased from 75 (1885—86) to 98 (1887—88).

How had the Dunlops acquired their wealth? What monies entered the Trust?

Here, we do not yet know the full story, but important elements are clear. The Dunlops were a wealthy couple, with assets and investments in both the USA and the UK. We have yet to uncover details about the origins of that wider wealth, and the full extent of the Dunlops’ properties in the USA up to 1847. However, we believe those properties stretched over several states in the American South and included at least one Virginian plantation, as well as other small properties and warehouses in Virginia probably connected to enslaved production. James and Nancy inherited that plantation from Nancy’s father (Jane’s maternal grandfather), the wealthy enslaver Charles Duncan. James kept in very close contact with its overseers while he lived in London, keen for it to expand and succeed. Most importantly, we know that from c.1800 to 1847, around 40 enslaved men and women lived and worked on that plantation. More than this, several secondary sources describe James Dunlop, born in Scotland in the 1760s, as someone involved in trade between Virginia and the UK. They sometimes term him a tobacco merchant.

In 1847, Nancy bequeathed ‘the wealth that belonged to’ James Dunlop and the plantation elsewhere, and we believe no proceeds from those arrangements entered the Trust which would support Jane Catherine Gamble during the latter part of her life. Instead, it benefitted from the sale or transfer of other elements of Nancy’s wealth previously located in either the USA or Britain. We are currently seeking to research those assets more fully.

Extract from a note in Jane Catherine Gamble’s hand, listing the Dunlops’ assets in the USA, 1847 (archive reference: GCPP Gamble 2/5pt).

Reflection

The picture we are left with is complex. The Virginian plantation, owned by Jane’s maternal grandfather, then by her aunt and uncle, was barely profitable in the decades leading up to 1850, despite James Dunlop’s efforts. Money from its sale didn’t enter the 1851 Trust, which Nancy decreed could only hold investments in ‘the parliamentary stocks or public funds of Great Britain’. We do not know the direct origins of the money so invested. Nevertheless, all the evidence suggests that Jane’s maternal family wealth, and that of her uncle James, which together supported her from childhood on, and from which her adult inheritance came, had been for at least two generations deeply connected to money made from the transportation and sale of goods produced by enslaved labour, and to the attitudes and beliefs that sustained that system, and allowed the degrading circumstances of the men and women who worked and lived on plantations. Money directly inherited by Jane, and then by Girton, may have been, in some eyes, ‘distanced’ from these origins and connections by time, and by the multi-layered processes of sale and reinvestment, but this cannot hide its troubling history.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: April 2023)

An account of Jane Catherine Gamble's life from a different perspective, written in 2018, is to be found under the Girton College Archive's short series, 'Glimpses of Girton'. View the article here.

Coming next: No. 2, May 2023

Facts and findings: Girton's Working Group 2020-22.

The steps College took to augment its knowledge of itself through the Legacies of Enslavement Working Group that was set up in 2020.