Past and future

Published: September 2024

As we look back on the enquiries and activities of Girton’s Legacies of Enslavement work, through its Working Group (LEWG) and Committee (LEC), it is clear that a goodly proportion of effort over the last four years has been concerned with the financial legacy of one particular benefactor, Jane Catherine Gamble. To the best of our knowledge, this legacy is Girton’s single most close link to plantation economies based on enslaved labour (see Girton Reflects no.1). It is in relation to it that we have been pressed to think most acutely about questions of restorative justice.

Previous episodes have presented a digest of our findings about Girton’s connections with late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century enslavement. We have included something of what we know about life on plantations and the conditions of chattel slavery, as well as the early funding of Girton and the effect of Gamble’s legacy. In this last episode, we reflect more broadly on the commitment to accountability (see Taking account) that has been our guide. Here we indicate how far our research has taken us. We also focus on the part that money has played in the whole story -- for both good and ill. Two financiers, either side of the Atlantic, introduce us to some of its complexities.

The two brokers

In the early 1800s, the flourishing business community of Richmond, Virginia, included a pair of brothers from the wealthy planter aristocracy. We know the elder brother, the university-educated John Grattan Gamble (1779-1852), as Jane’s father (although she later became the charge of her mother’s relatives, the Dunlops). Subsequent financial uncertainties meant that the brothers began to look elsewhere to recoup what had become losses. On the tide of British (and European) demand above all for cotton and sugar, they had by the mid-1820s became part of a migration of American people into territories further south, in their case Florida Territory, where they waged a campaign of forward-settlement against the indigenous inhabitants.

The elder brother was to specialise in cotton and tobacco, the younger in sugar. Who knows if any of the bales of cotton that John produced on his Florida plantations ended up in the ledger books of Nicholas Waterhouse and Sons in Liverpool. This would have been the time when Alfred Waterhouse Snr was still in the business. His father, Nicholas (1768-1823, see Girton Reflects no. 11), had traded in all kinds of goods, but Nicholas’s primary reputation was as a cotton broker. In addition to being a cotton importer in his own right, it was as a broker that he bought and sold on the part of other businesses, through the financial facilities – such as extended credit – that he made available. The facilitating role of money would have been evident.

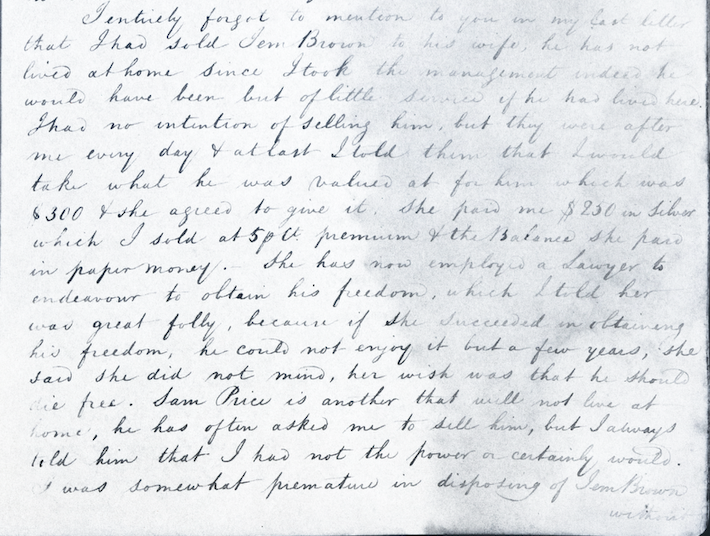

John Grattan Gamble had been a broker too. In the years leading up to what was, for the enslaved he took with him, an 830-mile forced march out of Virginia, he had become a broker, extending credit in the buying and selling of persons. We would nowadays call this people trafficking, regardless of how respectable it was in the eyes of some. With many on the move, there was business to be done in facilitating the flow of persons between buyers and sellers. The sums were substantial: this was capital investment. But what of those whose only contact with significant amounts of money would have been the price that they or their fellows fetched – or, in exceptional circumstances, the sums they might have put together over the years to redeem a close relative? This is what Mrs Brown did in 1816 for her husband, Jem, enslaved on the Roslin Plantation owned by Jane’s aunt and uncle, James and Nancy Dunlop (see Girton Reflects no. 8). One wonders how, as it changed hands, such money would lodge in their memories.

Excerpt from a letter from William McLean to James Dunlop, 28 August 1816. The Roslin Papers, Library of Virginia (LVA), Accession 23873, part 2. It tells of the $300 Mrs Brown used to buy her ageing husband, with his eventual freedom in sight (for a transcription see GR8).

Following the money

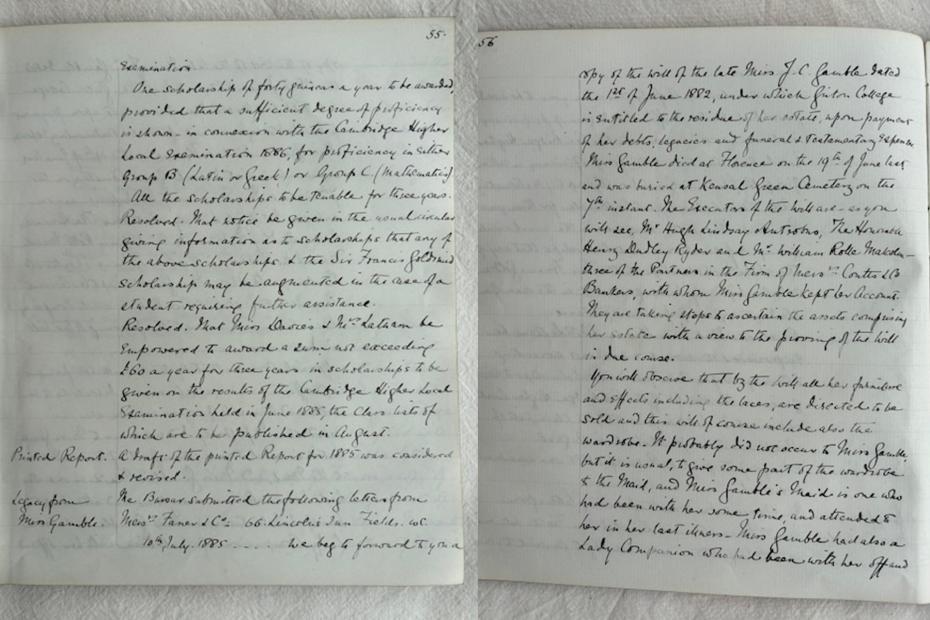

It hardly needs be said that without the facilitation of money Girton would never have been built, nor would Nicholas Waterhouse’s grandson have designed the Tower and Tower Wing. Nor, for that matter, would the present enquiries have taken place. In fact money has been a huge facilitation in another sense altogether: as a research tool. By ‘following the money’, College has discovered new connections, new histories.

Whatever the attitudes and views of Girton’s early supporters at the time, theirs was a world in which in many senses we no longer live. But we do live in a world that is heir to the wealth that they contributed to the foundation of the College. This is where a significant strand of Girton’s present-day connections lies. It enables our accounts to become a form of accountability, a recognition of the entanglements between wealth and generosity, liberty and oppression. This series has recorded the efforts of many early donors who saw a future for higher education for women; it is with a very different kind of recognition that we have been able to document, in certain significant cases, where funds would not have been generated, or added to, but for the labour of enslaved people. These are connections created through the flow of money. While money is the means to finding them, it is in itself also a reason why those connections continue to matter.

Excerpt from Girton Executive Committee minutes noting the recent letter from London solicitors, Farrar and Co, giving news of the Gamble bequest, 24 July 1885 (archive reference: GCGB 2/1/9pt).

Much of that nineteenth-century wealth gained from enslavement became in Britain transmuted into diverse channels and enterprises, so that over time its history was detached from those origins. Recovering some of the pathways, connected with greater or lesser directness to practices of enslavement, has been a process of re-attachment.

Furthering research

Through the different topics that its episodes have brought into focus, Girton Reflects has literally reflected the findings that arose from College’s original request (see Girton Reflects no. 2) for research into any possible connections with enslavement. The character of that research has been largely indicative, laying out the likely scope. Indeed, much work has been directed towards establishing the basis of (present and future) knowledge. This entails discovering where to look in the first place and hence tracking down sources of information; it also includes negative confirmation – eliminating less fruitful leads from further enquiry. Bringing things to light is not of course the same as analysing them. To date, much of what gives us a general picture as yet remains unexamined in detail. Yet the detail is so pertinent: only recently we have found documents that give the first hints that Jane Gamble was not simply heir to proceeds made from the Roslin Plantation near Richmond, which is what we thought at the time of writing the first in this series (see Girton Reflects no. 1). It looks as though we may confirm that for a few years at least she was a part-owner.

The surviving central section of the original Roslin Plantation House, moved and rebuilt on a nearby site in the early twentieth century, 2024. Image provided by Dr Maggie Kalenak.

In effect, this last episode of Girton Reflects closes a chapter of Girton’s endeavour. It is one in which College funded first LEWG and then LEC to pursue Council's request. While this will continue for a while, a new basis has been created to broaden out these activities. LEC has set up a Research Hub that will be outward facing in two respects. First, it will put in place the mechanisms for making current research findings generally accessible, within College and without, and in a user-friendly form for diverse levels of scholarship. This will include both Girton’s own records and collections of original papers that we have had digitised. Second, it will explore funding possibilities for attracting and supporting researchers, both from the university student body and more widely. While the rationale for such funding would point to projects bearing on the overall aspirations of Girton’s LE enquiries, fresh ventures will no doubt also reflect future interests.

LEC itself is conscious of many areas that would profit from further investigation, as well as of larger questions of which Legacies of Enslavement is only a part. Of course, for any research, one can always broaden one’s scope or, conversely, add more particulars. Apart from interests that others may bring, LEC’s own skill will be in discerning where one might uncover the pertinent detail – as in the instance already mentioned – or the specific lead that enlarges what one already knows but in effect only half-knows. To keep with Jane Gamble, for example, we now have the material – not yet fully explored – to judge the role that Roslin Plantation played among all the business ventures undertaken by James and Nancy Dunlop, the relatives who formed the fortune from which she inherited.

Keeping these issues alive is a form of on-going memorialisation, although what for Girton is also the fostering of continuing engagement through research might carry quite different meanings for those whose personal family histories entail their own memory work in relation to the formerly enslaved.

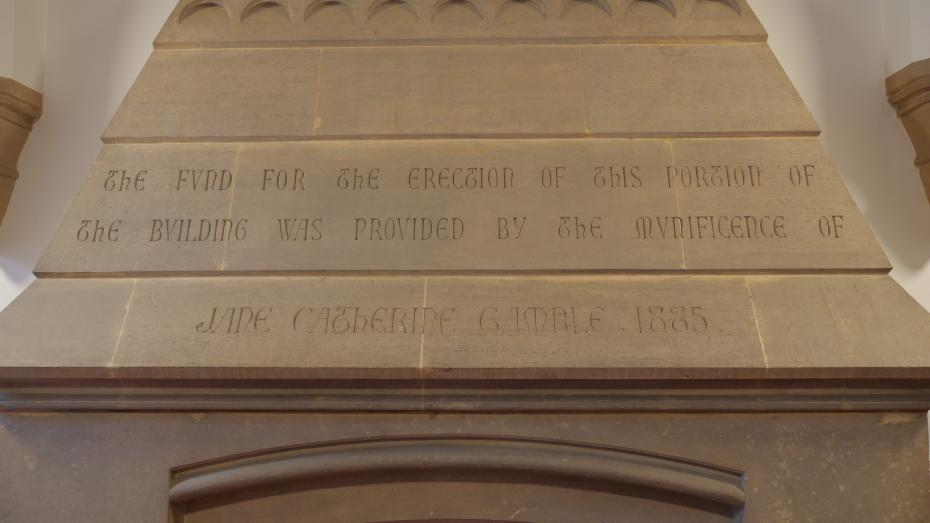

The inscription in the College Entrance Hall in Tower Wing. The wording was agreed by the Executive Committee on 16 November 1888; on 1 February 1889 it was decided that this would be ‘incised on the stone chimney piece in the entrance hall of the College’. (Photograph copyright Girton College 2024.)

Chattel slavery and restorative justice

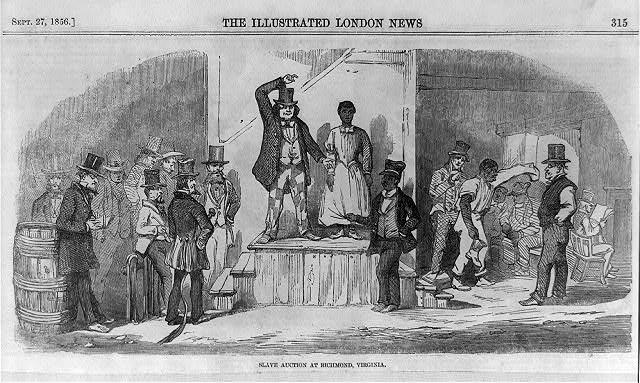

It is important to keep at the forefront of one’s mind that the kind of chattel slavery at issue, as Betty Wood demonstrated (see Girton Reflects no. 7), was a historically specific instance of coerced labour. This arose at a time of expanding transatlantic commerce – the notorious ‘middle passage’ was one arm of the trading triangle between Britain, West Africa and the Americas – and continued to flourish in the United States in an era of increasing financialisation. Our two brokers, one more directly than the other, provided a facilitating mechanism (credit) for the nineteenth-century flow of people and goods, and of people as goods. The forced migration south, out of areas such as Virginia, may well have included the most able-bodied of those working on Roslin. As was noted in Girton Reflects no. 4, that upheaval of enslaved persons was so devastating that it is sometimes referred to as the ‘second middle passage’.

‘Slave Auction at Richmond, Virginia’. The Illustrated London News, 27 September 1856, p. 315. London. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-15398.

One tragedy is the permanent mark that chattel slavery left on society, on both sides of the Atlantic. That, too became transmuted, appearing today in terms of ongoing racial discriminations for which people find all kinds of reasons. A restoration of the historical links, their re-attachment as a form of memorialisation, is also a gesture to those who more directly than others continue to suffer the consequences, wherever they are. Here money comes into its own as another kind of facilitator. The financial support that Girton has given to the enquires carried out by LEWG and LEC is that kind of gesture. Through the expenditure of money in the light of new knowledge about the funds from which it has profited, Girton has already taken a reparative step.

In the case of Nicholas Waterhouse’s grandson, and the stamp he set on College’s features, such a gesture must join our generalised acknowledgement of the sources on which much nineteenth-century prosperity was based. As for John Grattan Gamble’s daughter, she received – as far as we currently know – nothing from him, but inherited from his in-laws, the Dunlop aunt and uncle who brought her up. We now have considerable knowledge of one of their concerns, the Roslin Plantation. This includes some information (not nearly enough as we would like) on those men and women who were enslaved there. And of course we have the financial records, already published (see Girton Reflects no. 9), of the legacy Jane left to Girton.

Girton Tower and Tower Wing, circa 1890 (archive reference: GCPH 3/1/1). This was designed by Alfred Waterhouse Jnr and financed from the Gamble bequest.

Reflection

College as a whole has not yet engaged with the principles of reparation and restorative justice: that discussion lies in the future. Who knows in what ways the College might find the resources to turn money into a facilitator for transatlantic relations. In the meanwhile, perhaps this ongoing restoration of our history may also be welcomed by others as in turn a restorative contribution to their own histories and to the stories of families that they might in the future wish to tell.