To mark the centenary of the death, on 13 July 1921, of Girton’s principal originator, Emily Davies, we present a tribute to her life and work, and an account of her central role in establishing the College for Women and shaping the early years of Girton College Cambridge.

Exhibition

Tributes to Emily Davies

Fanfare to Girton

Although Emily Davies is one of four figures represented in the College crest, it is highly unlikely that ‘the College for Women’ would have been founded when it was, or taken the course it has, without her vision and determination. So, when that College celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2019, formalities were opened with a newly commissioned ‘Fanfare to Girton’ which explicitly references Emily’s Welsh heritage as well as paying tribute to the five pioneering women students who joined her in Hitchin on 16 October, 1869.

Here, to open our exhibition, is Jasper Dommett’s Fanfare to Girton, recorded for us by the brass band of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, conducted by Jasper Dommett. The images are from our Girton150 Festival showing the band's visit with both Jasper and their Musical Director, Dr Bob Childs.

Fanfare to Girton

Recognising Emily Davies

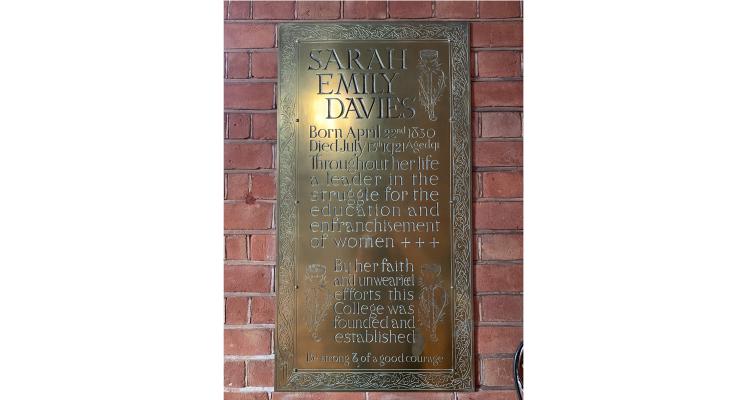

There are many references to Emily Davies to be found in Girton today. These include the Blue Plaque on the Tower, and the Emily Davies Courtyard by the original entrance to the College (shown in the last slide of the Fanfare above). We also have the Emily Davies conference rooms – formerly her offices – which can be booked for events and meetings. View our Conference webpages.

Emily’s contribution to College was the centrepiece of the annual Ceremony for the Commemoration of Benefactors in 2019, when the current Mistress, Professor Susan J. Smith read this tribute (View PDF).

An Exhibition of Emily Davies’ Life and Work

This exhibition was written for the College’s 2019 Commemoration of Benefactors by Hazel Mills, College Historian, and Hannah Westall, Archivist. The facts in this exhibition are correct to our best current knowledge at that time.

Caption: Portrait of Emily Davies by Rudolf Lehmann, 1880 (archive reference: GCPH 5/4/2).

Emily Davies (1830–1921)

Sarah Emily Davies (always known as Emily) is often best remembered for her role in the foundation of ‘The College for Women, Hitchin’ in 1869, which was renamed Girton College in 1872. With Barbara Bodichon, she was certainly a leading figure in that campaign. However, this was neither the beginning nor the end of her pioneering contributions to the political, educational and social reform movements of her time. This exhibition illustrates aspects of Emily’s life and work, taking in her friendships and some of the campaigns in which she played a crucial role. These include the foundation of Girton and her long subsequent relationship with the College.

Emily was born in 1830 and spent her later childhood in Gateshead, near Newcastle. Like many middle-class young women of the time, she had a more limited education than her brothers, and was expected to be content with ‘home duties’ and family visits, at least until any marriage. However, in part through a network of female friends in Gateshead and in London, Emily was introduced to ideas about improving the position of women in society and to political campaigning on behalf of girls and women. She became associated with the women of the Langham Place Group and with the English Woman’s Journal, published from 1858 to 1864.

After her father's death, Emily and her mother moved to London in 1862. This enabled Emily to play a more active role in the women’s movement. She became very involved in campaigns to improve women’s education, including to open University of London degrees to women, to admit girls to the Cambridge University Local Examinations, and for the inclusion of girls’ schools in the Schools Inquiry Commission of 1864–1868. These campaigns led to other activities. She was a founding member of the Kensington Society; founded the London Association of Schoolmistresses; and in the early 1870s became one of the first women elected to the London School Board. In the mid-1860s she was also active in the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Although several of her early successes were in securing improvements in girls’ secondary education, as the 1860s progressed Emily Davies’ primary focus became the provision of higher education for women. Her vision, and hard work campaigning to establish what was to become Girton College, helped provide the first opportunity in Britain for women to receive a university education on exactly the same terms as men.

After her retirement from Girton in 1904, Emily resumed a more active involvement in the suffrage movement. Throughout her life she was a highly-organised and vigorous committee woman, imbued with a strong work ethic and a will of iron. She published extensively on educational and suffrage issues and was, for periods, editor of the English Woman's Journal and of the Victoria Magazine.

Caption: Portrait of Emily Davies in 1851 (aged 21) by Annabella Mason. Annabella and Hannah Mason were family friends and frequent visitors to the Davies home in Gateshead. Emily Davies noted that Annabella, ‘used to take likenesses, and our albums contained sketches of Jane, William and myself.’ (archive reference: GCPH 5/4/8).

Childhood and young adulthood

Emily Davies was born in 1830 in Southampton. Her father, Anglican clergyman John Davies, was born in Llandewi Brefy in Cardiganshire. His father was a Welsh farmer. John Davies obtained a B.D. from Queen’s College, Cambridge, and wrote several works of theology.

Soon after her birth, Emily’s family moved back to Chichester, where her parents had previously lived. In 1840, when Emily was nine years old, they moved to Gateshead, near Newcastle, where, through the patronage of a former Bishop of Chichester, John Davies had been offered the Anglican living. Gateshead would remain Emily’s home until 1862 when, following the death of her father, she and her mother moved to 17, Cunningham Square, London, to be close to her older brother, John Llewelyn Davies.

In Chichester, Emily had learnt ‘a little Latin’ for her own pleasure, and because her brothers were doing it, but this stopped before the family moved north. In Gateshead, Emily’s three brothers were first taught in a small class taken by one of their father’s curates. Then John Llewelyn and William were sent to Repton School, before attending Cambridge University. The youngest son, Henry, went to Rugby School and was then articled to a solicitor. In contrast, Emily and her sister Jane remained in Gateshead. For a few months they attended a small day school for girls but after that their education was based at home. They had ‘some lessons’ in French and Italian and were also taught some music. ‘Our education,’ Emily would later recall, ‘answered to the description of that of clergymen’s daughters generally … “Do they go to school? No. Do they have governesses at home? No. They have lessons and get on as they can”’.

In Gateshead Emily used to write ‘themes’ – small, weekly compositions in English which were looked over by her father. With one of her brothers, she also wrote little ‘newspapers’, which many years later she described as consisting chiefly of short ‘denunciations and warnings against Popery and Tractarianism’ written in English, French, Italian, German and Latin. They were modelled, she said, on the Evangelical paper The Record, which reflected the family’s ‘sentiments’ at the time. The children also played at being candidates for parliamentary elections.

Alongside any studies, Emily and Jane were expected to help their mother in the house. ‘Our muslins, collars and cuffs etc, were washed at home and my mother, Jane and I did the ironing about once a month in a storeroom in the basement’, she recalled. ‘We did mending also, but not much of dressmaking or millinery’. Religion was an important part of daily life; the family gathered for prayers each evening.

Caption: Handcoloured woodblock engraving from the Illustrated London News, 14 October 1854, showing the devastating fire in Newcastle and Gateshead. Emily would have witnessed the destruction and havoc caused by this tragic event, which killed 53 people (reference: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Newcastle_and_Gateshead_Great_Fire_1854_-_Illustrated_London_News.jpg)

Significant friendships

In Gateshead, and then in London, Emily had a circle of close women friends, many of whom became supporters of Girton College. Jane Crow and her sister, Anne Crow, later Austin (always known as Annie), moved to Gateshead with their family in 1848. Both became Emily’s friends. Annie helped Emily to found a weekly reading class in Gateshead for servants and young women, held in the Austin home. Here, Emily’s emerging interest in women’s education grew stronger. Widowed relatively young, Annie often visited Emily in London and assisted her in various campaigns. In 1869, she helped prepare Benslow House for the first students and, in 1870, she became the third Mistress of the College for Women.

Before arriving in Gateshead, the Crow sisters had attended a small girls’ school in Blackheath, south London, where they had become friends with Elizabeth Garrett and her sister, Louie. In 1854, the Garretts visited Jane and Annie in Gateshead, and so began the long friendship between Emily and Elizabeth Garrett, later Garrett Anderson.

Jane Crow was with Emily when another important friendship began. In 1858, the two Gateshead friends travelled to Algiers to visit Emily’s younger brother, Henry, there to recover his health. In Algiers, Emily met Barbara Bodichon, married to a French-Algerian doctor, and her sister Annie Leigh Smith, also visiting the country. Barbara and Emily became close friends. Soon Barbara began introducing Emily to feminist circles in London. These connections grew in importance in Emily’s life after her move to the capital in 1862. Among those she met were [Elizabeth] Adelaide Manning and her stepmother Charlotte Manning. Both became friends and were early supporters of the College. Charlotte became the first Mistress at Benslow House.

Before Emily left Gateshead, a further important friendship began. After a visit to London and to Langham Place, Emily established a Gateshead branch of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. Among the local figures who agreed to sit on its new Committee was Anna Richardson, who quickly became a very close friend and confidante. Anna was the daughter of a Newcastle leather manufacturer. She had attended the Friends’ School at Lewes, Sussex, and spent time in Paris and in London. Her wider Quaker family were prominent abolitionists. Anna encouraged Emily to read more extensively; together they discussed books, such as the novels of George Eliot. Anna also helped Emily to learn some Greek, and the two women started attending ‘Lectures for Ladies’ in Newcastle. Anna would encourage Emily in all her work for women’s causes in the 1860s and particularly in the campaign to open the College for Women. Anna may have been one of those who introduced Emily to Hitchin, home to a number of prosperous Quaker families.

Caption: Possibly a photograph of Anne Austin, née Crow, by an unknown photographer, circa 1870 (archive reference: GCPH 5/3/1).

Caption: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson by an unknown photographer, not dated (archive reference: GCPH 4/31).

Caption: Barbara Bodichon, taken in Algiers, by an unknown photographer, circa 1870 (archive reference: GCPH 4/2/7).

![[Elizabeth] Adelaide Manning by an unknown photographer, circa 1905 (archive reference: GCPH 4/5/1)](/sites/default/files/styles/930_scale/public/images/Image7-GCPH4-5-1ElizabethAdelaideManning1905bw600dpi.jpg?itok=1nipLsdb)

Caption: [Elizabeth] Adelaide Manning by an unknown photographer, circa 1905 (archive reference: GCPH 4/5/1).

London University degrees for women 1862

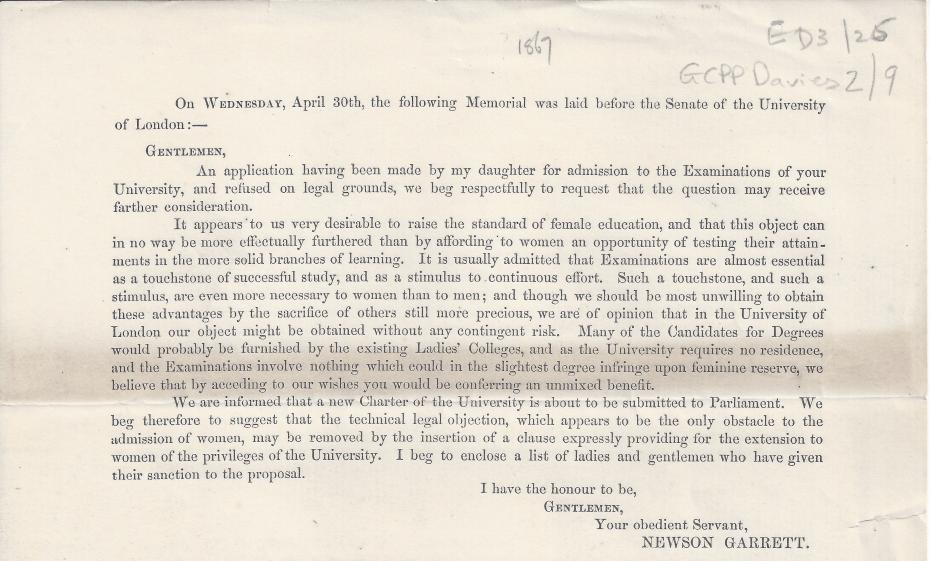

By 1859, Emily Davies was friends with Elizabeth Garrett (later Garrett Anderson) and had met members of the Langham Place group in London. She encouraged Elizabeth in her ambition to qualify as a doctor. By February 1861, Emily was receiving long letters from her friend describing her efforts and experiences. After moving to London, Emily supported the on-going campaign to enable Elizabeth to complete her training and to be licenced. Newson Garrett, Elizabeth’s father, also strongly supported his daughter’s ambitions.

In 1862, to further her training, Newson and Emily set to work with Elizabeth to seek permission for her to enter the matriculation examination of London University. This application was rejected. They then decided to seek the inclusion of a clause in the proposed new charter of the University of London permitting the admission of women. Emily became the first Honorary Secretary of a committee (at first informal) linked to this campaign. Despite some support within the University, the proposal was narrowly rejected. Women would be admitted to London University degree examinations in 1878.

Elizabeth went onto complete her training and in 1865 she was licensed as a Doctor by the Society of Apothecaries. This entitled her to have her name entered on the medical register. She was the first woman doctor to qualify in Britain.

Caption: Memorial laid before the Senate of the University of London on 30 April 1862 by Newson Garrett (archive reference: GCPP Davies 2/9).

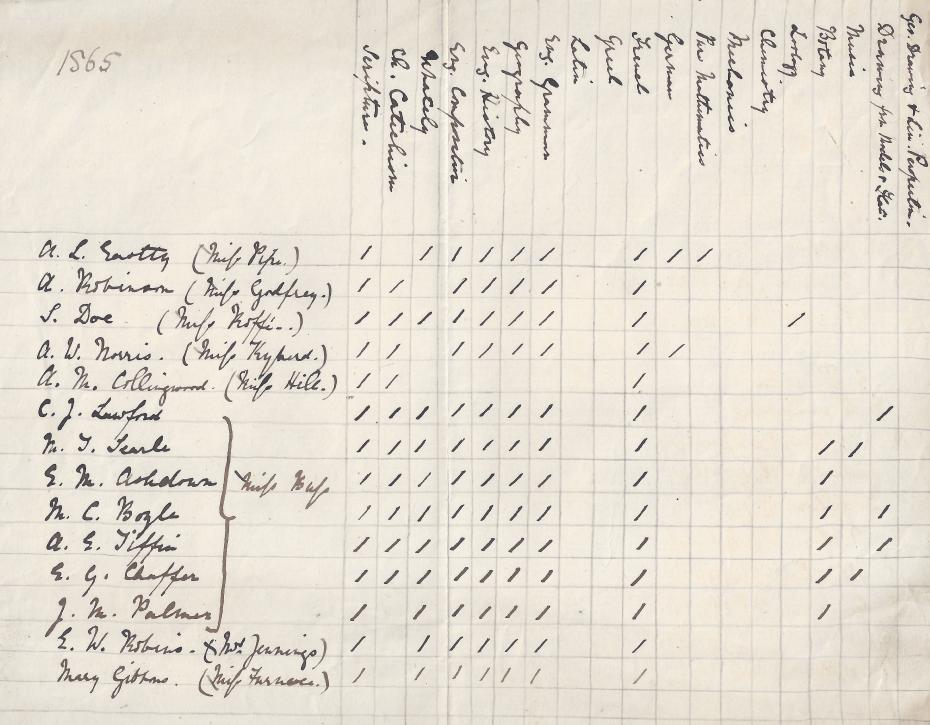

Admission of girls to University Local Examinations 1862–1865

In 1862, Emily set up a committee with a view to obtaining the admission of girls to the University Local Examinations for schoolboys (started by Oxford University in 1857 and by Cambridge in 1858). These examinations were intended as a school leaving qualification. Access for girls was allowed by Cambridge University experimentally in 1863. This was judged to have been a success and, two years later, the admission of girls to the ‘Cambridge Locals’ was made permanent. During this campaign Emily made many important contacts. One of these was Henry Tomkinson, who would later become an early and long-serving supporter of Girton College.

Caption: Presumed to be a register of girls present at the 1865 Cambridge Local Examinations (archive reference: GCPP Davies 8/133).

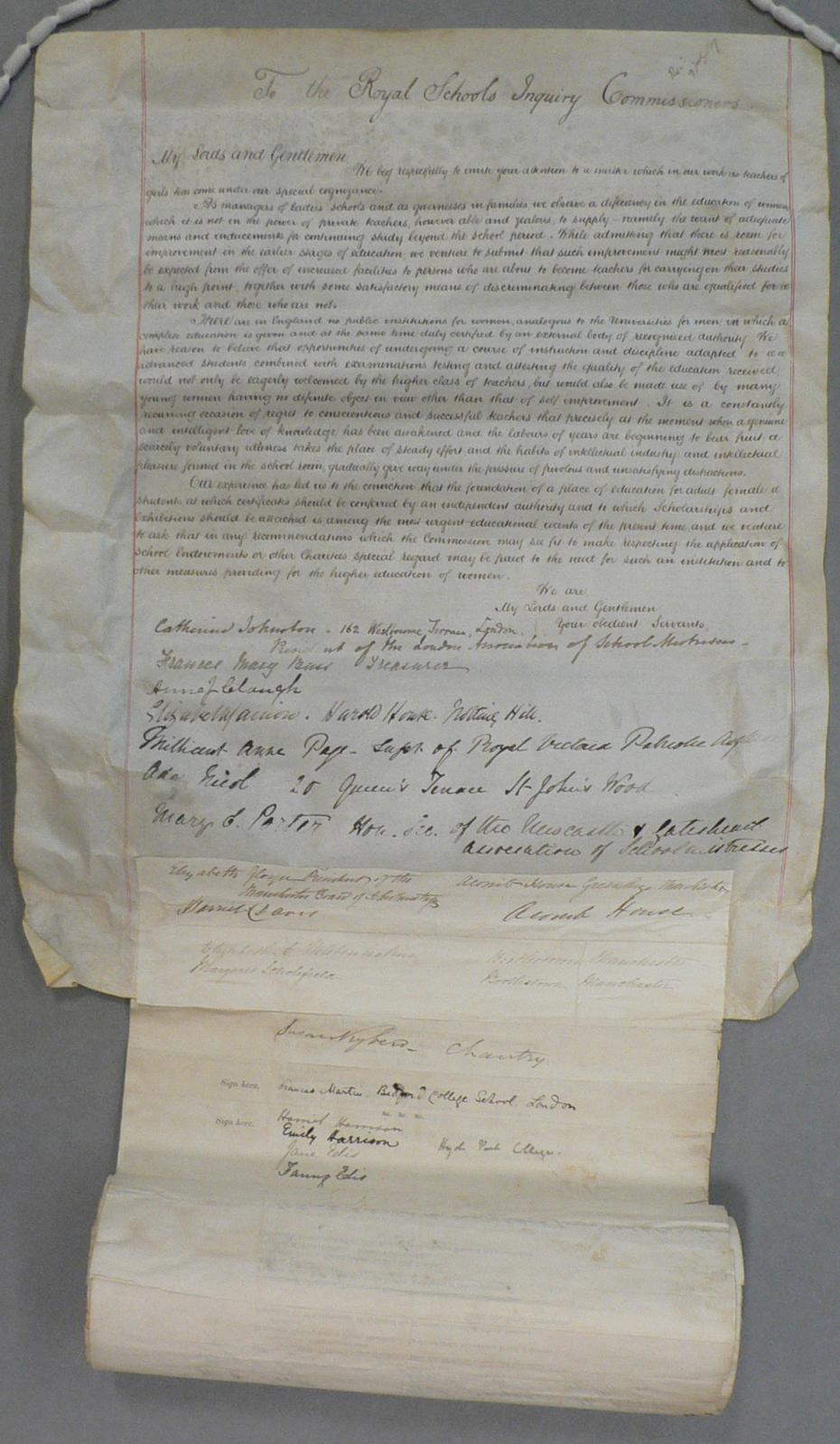

Schools Inquiry Commission 1864–1868

The government appointed a new Schools Inquiry Commission in December 1864 (the Taunton Commission) to examine and make recommendations to improve middle-class secondary education in England and Wales. Emily campaigned successfully for the inclusion of girls’ schools in the remit of the Commission. On 30 November 1865, Emily gave evidence, in person, on the state of female education. She was the first of nine female witnesses, making her the first woman to give evidence in person to a royal commission as an expert witness. Among the other female witnesses were Dorothea Beale, Principal of Cheltenham Ladies’ College and Frances Buss, Headmistress of the North London Collegiate School.

The Commission proved to be of great national importance. It highlighted the fact that secondary education was far from satisfactory and needed reform. The inclusion of girls’ schools in the Commission’s remit was a significant step forward for girl’s education. The publication of the Commission’s report in 1868 led to the Endowed Schools Act and other reforms.

Caption: 'An appeal for the provision of facilities for the higher education of women, 1867'. This memorial was sent by Emily to the Schools Inquiry Commission (the Taunton Commission). It was signed by 696 individuals, including 521 teachers of girls (archive reference: GCPP Davies 6/21).

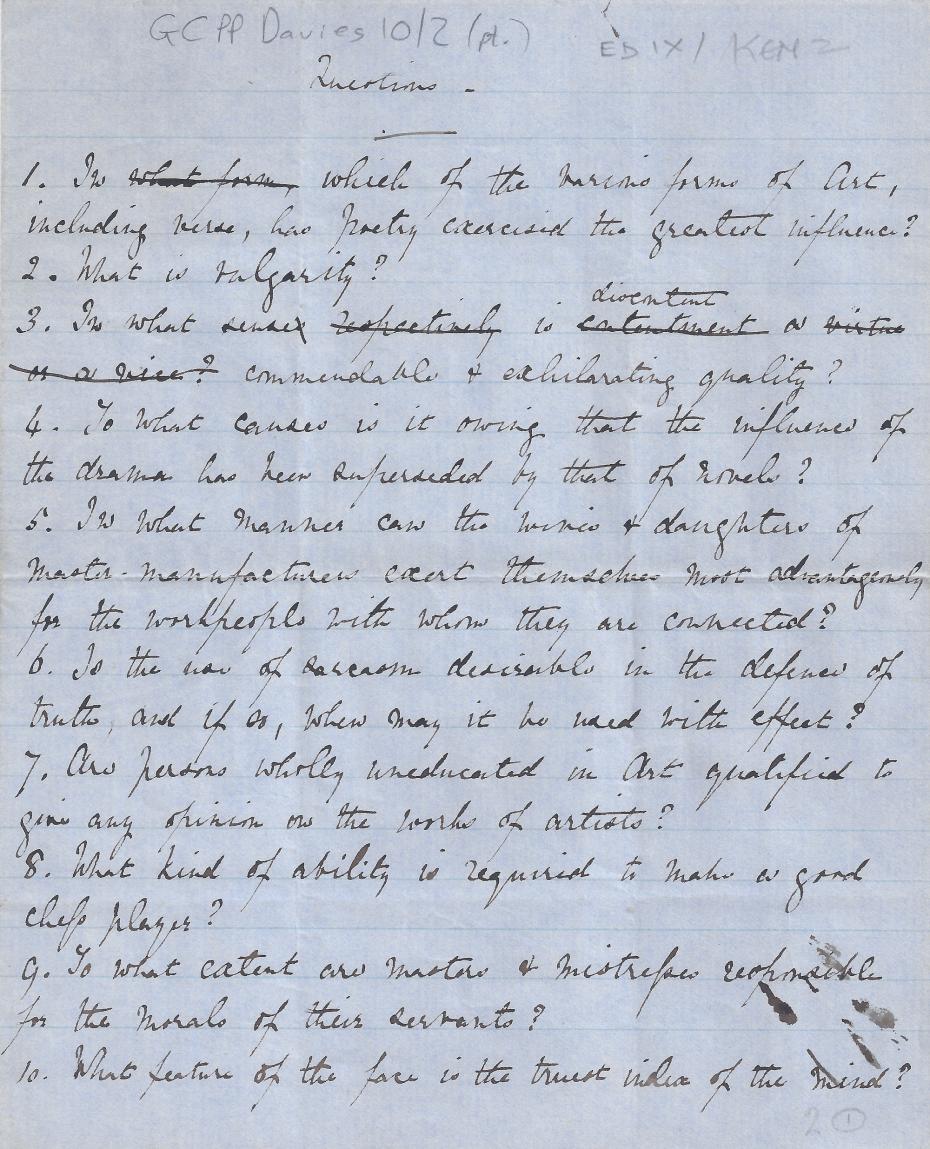

Kensington Society 1865–1868

The Kensington Society was a discussion group where women eager for change could meet and debate issues related to improving the position of women in society. Membership was by personal invitation and Emily, as Secretary, brought together women ‘having more or less common interests and aims’. Many were already friends or were connected by other enterprises such as the Langham Place Group and the English Woman’s Journal. The Society met regularly at 44 Phillimore Gardens, Kensington, the house of its President, Charlotte Manning. Members included Barbara Bodichon, Dorothea Beale, Frances Buss, Elizabeth Garrett, Anne Clough, and Anna Swanwick.

Questions for debate were issued four times a year and members might speak at the meetings or submit written answers. One subject addressed was the admission of women to University Local Examinations. However, the lasting achievement of the Society was the collection and delivery, on 7 June 1866, of a petition to parliament demanding women's suffrage.

Caption: List of questions for discussion in the Kensington Society, not dated (archive reference: GCPP Davies 10/2pt).

Women's suffrage, 1866 and later

Emily's early involvement with suffrage campaigning focussed on electoral reform and the extension of the franchise to women on an equal basis with men. In 1866, she and Barbara Bodichon as members of the Kensington Society drafted a petition asking Parliament to grant the vote to women with the same property qualifications as male voters. Nearly 1,500 signatories were gathered and the petition was taken to the Palace of Westminster for John Stuart Mill, MP, to present in the House of Commons. Unsurprisingly this reform was not considered at this time.

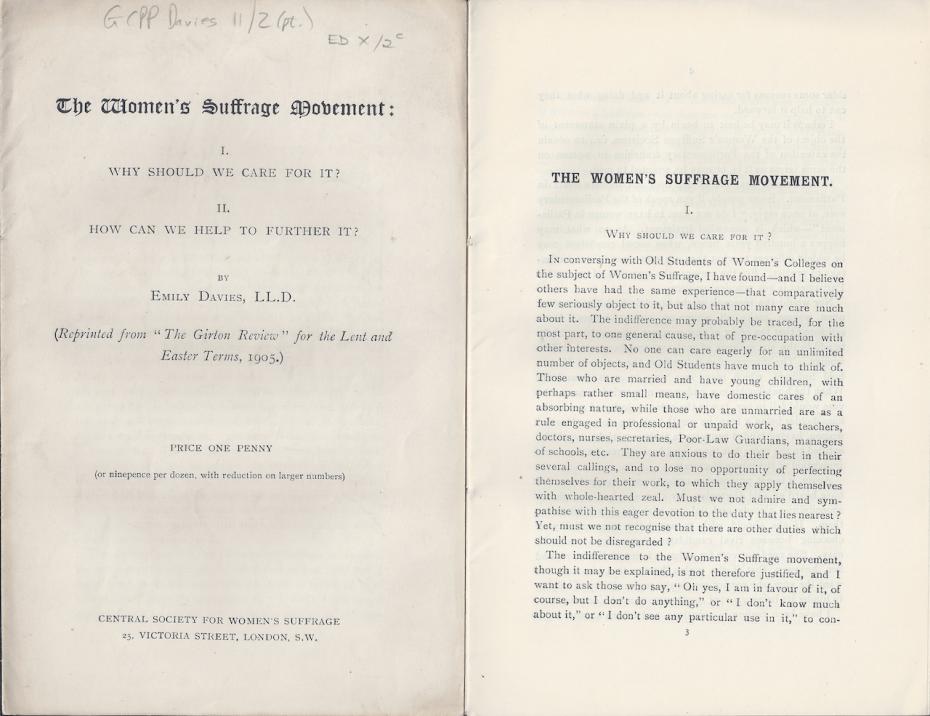

After 1866, Emily became disenchanted with the more radical members of the suffrage movement, believing that their ‘extremism’ did the cause no good. She made the decision to concentrate instead on the establishment of ‘The College for Women’ and remained largely silent on suffrage until the 1890s. Then, however, with a much-expanded Girton in a more secure position, Emily returned to active work for women’s votes. As well as participating in deputations and processions, she spoke to meetings large and small, often alongside younger suffragists, including former Girton students. National newspapers hailed her as ‘Britain’s oldest suffragist’, as in the photo taken at the London suffrage procession of 1908. In December 1918, when British women voted for the first time in national elections, 88-year-old Emily Davies was one of those who proudly entered the polling stations.

Caption: ‘The Women’s suffrage movement: why should we care for it and how can we help further it?’ by Emily Davies. Reprinted from the Girton Review for the Lent and Easter Terms, 1905 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 11/2).

Caption: A picture from the Manchester Guardian, 15 June 1908, showing 78-year-old Emily Davies (second from the right) as one of the ‘leaders of the procession’ that marched in London two days earlier in support of women’s suffrage (reference: Newspaper Collection, West Room, Cambridge University Library).

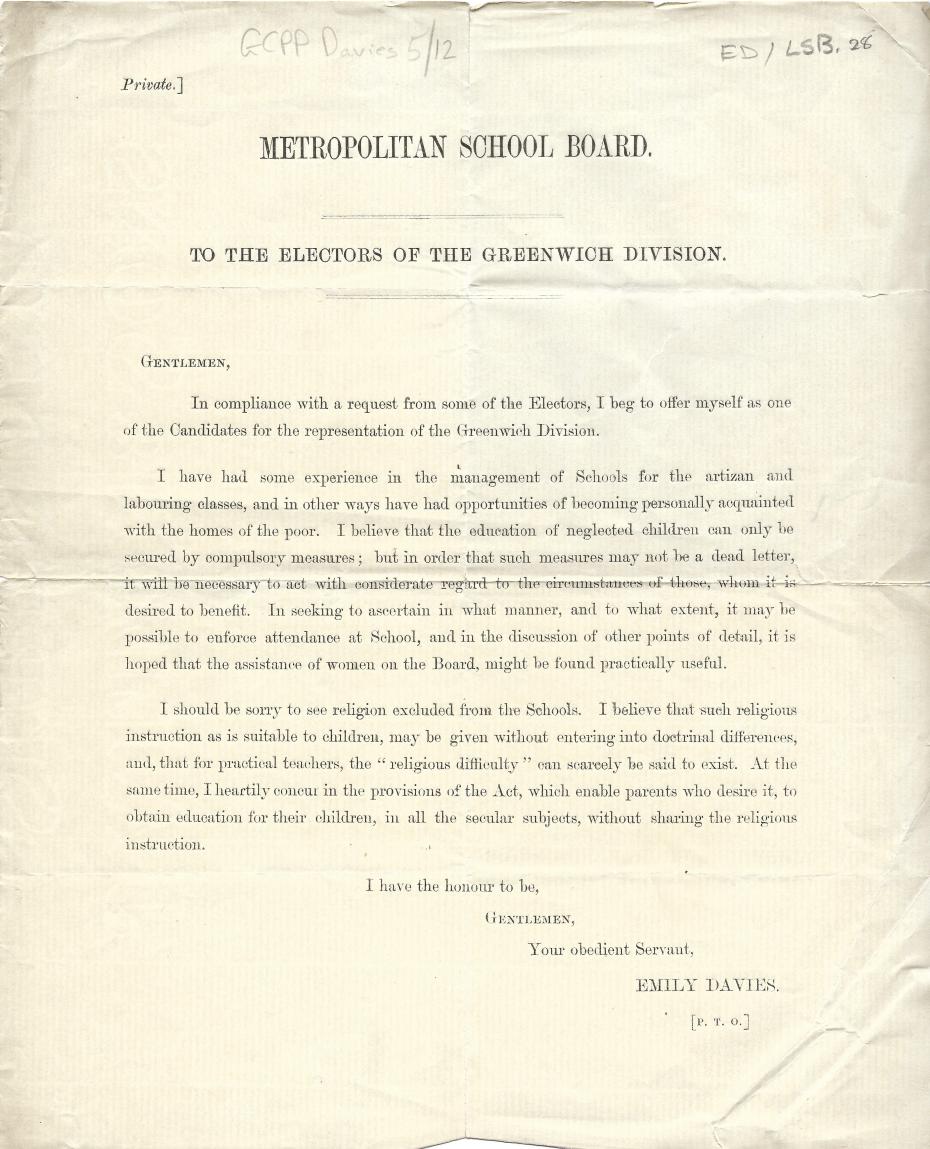

London School Board 1870–1873

The 1870 Education Act was the first piece of legislation to deal specifically with the provision of elementary education in Britain. The Act allowed voluntary schools to carry on unchanged, but established a system of school boards to build and manage schools in areas where they were needed. The boards were locally-elected bodies; any adult could stand for election, including women.

In late 1870, Emily and Elizabeth Garrett were the two first women elected to the London School Board, Emily as a member for the Greenwich Division and Elizabeth Garrett as a member for the St Marylebone Division. Emily sat on two of the Board’s standing committees: the Statistical Committee and the Bye-Laws Committee. Elizabeth Garrett sat on the Statistical Committee and the Officer and Clerks Committee. However, both women struggled with their existing workloads, especially as Emily’s attention was now firmly focussed on Girton College. Neither stood for re-election in October 1873 but were gratified to be replaced by two women, Elizabeth’s sister, Alice Cowell, and Jane Chessar.

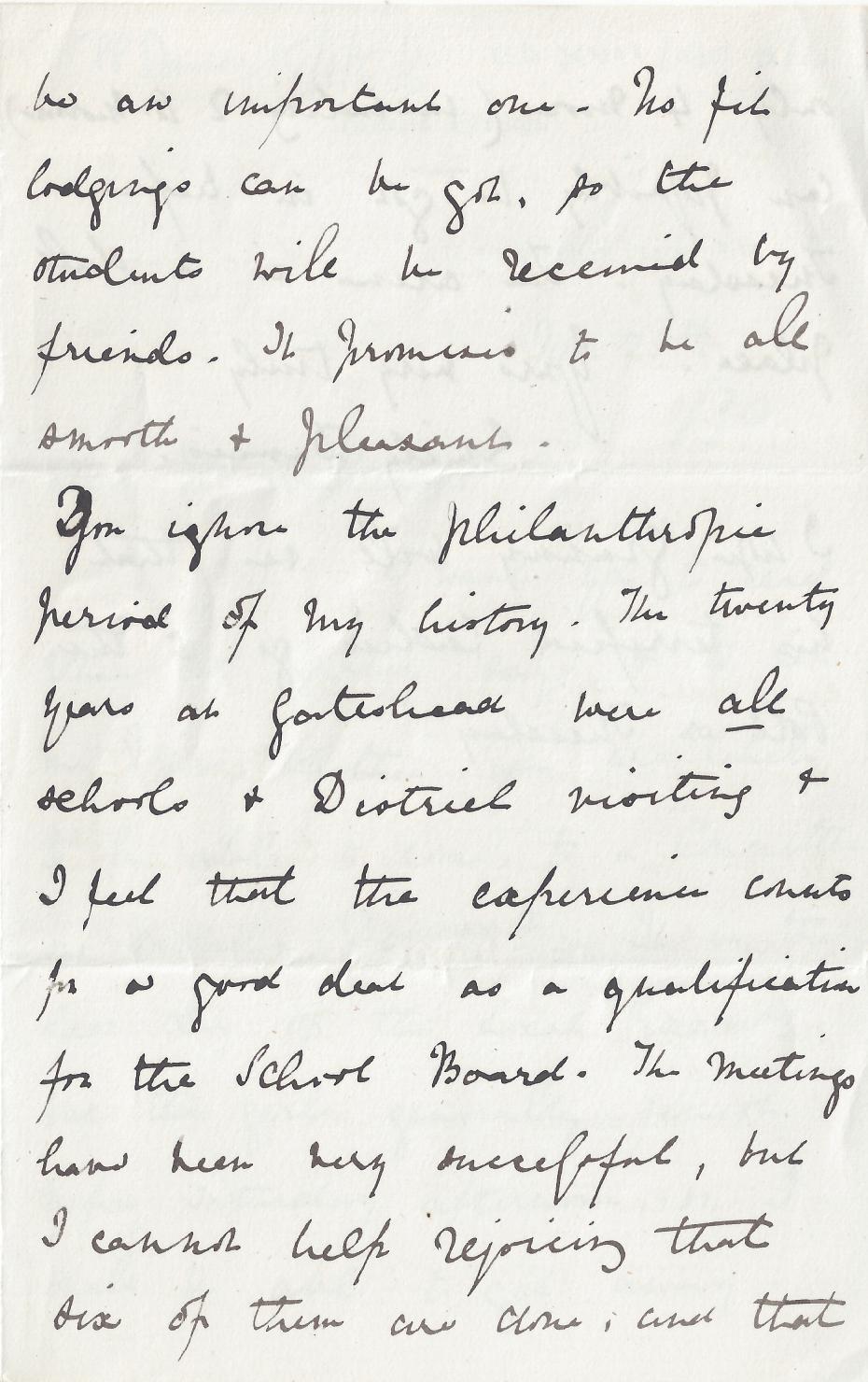

Caption: Part of a letter from Emily to Henry Tomkinson, 25 November 1870. Emily describes the suitability of her candidacy for the London School Board: ‘You ignore the philanthropic period of my history. The twenty years at Gateshead were all schools and District visiting and I feel that the experience counts for a good deal as a qualification for the School Board’ (archive reference: GCPP Davies 15/1/5/6pt).

Caption: Circular letter from Emily Davies to the Electors of the Greenwich Division, Metropolitan School Board, November 1870 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 5/12).

The founding of Girton College

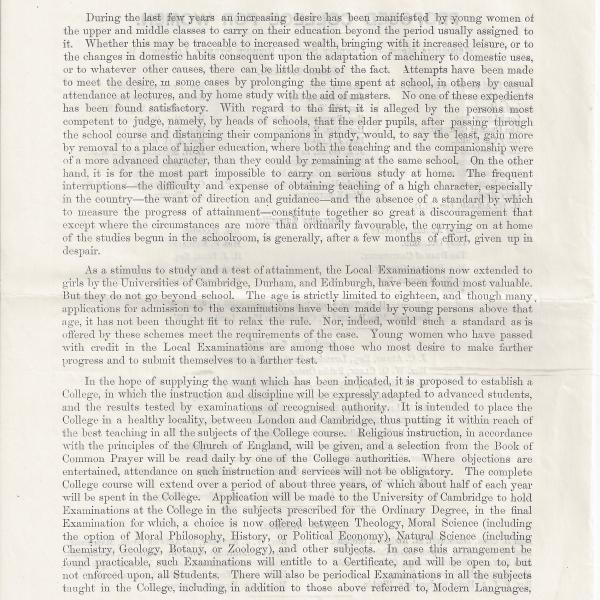

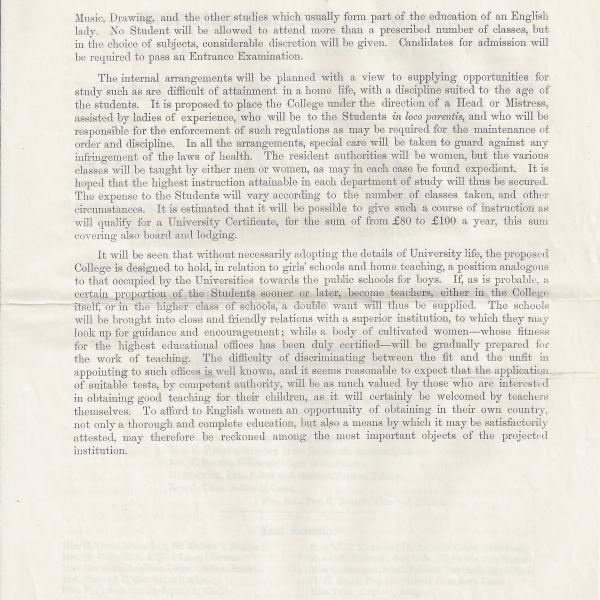

In 1866, Emily Davies published her first and perhaps most influential book, The higher education of women. It presented the case for opening up professional careers and university courses to women. Emily argued that many differences between men and women were matters of convention, not of biology. At this point no British university had opened its degree examinations to women students.

In the same year, Emily founded the London Schoolmistresses’ Association. She later wrote that it was on 6 October 1866, after attending a meeting of schoolmistresses in Manchester, that she first articulated her proposal to found a new college. By December 1866, she had drafted a short ‘programme’ stating the need for a university ‘College for Women’. The following year she formed a College Committee to raise £30,000 to build such a college. The earliest members of this committee were: Lady Augusta Stanley, Henry Alford, Emilia Gurney, Charlotte Manning, Henry Tomkinson, Fanny Metcalfe, George Hastings, James Heywood, Henry Roby, John Robert Seeley, and Sedley Taylor. Emily was Secretary. Barbara Bodichon joined in 1869; Lady Stanley of Alderley in 1872.

Emily was one of the early subscribers who each gave £100 to the College Fund (opened in 1867). However, despite a promise of £1,000 from Barbara Bodichon, by July 1868 only around £2,000 had been donated or promised. It was decided not to await the full amount required to build but instead to open the College in a temporary, rented home, whilst fundraising continued. On Saturday 16 October 1869, the College for Women formally opened its doors in Benslow House, Hitchin.

From October 1866 until 1904, a great deal of Emily’s work was focussed on Girton and on improving the position of women in Cambridge University. For the College she campaigned tirelessly to raise money for buildings and scholarships, and to see student numbers increase as quickly as possible; from 1872 to 1875 she was the resident Mistress, directly supervising the 1873 move from Hitchin to Girton; from 1875 to 1904 she was a very frequent visitor, overseeing much of the life and decisions of the College and its students. Until 1904 she was also Secretary, then Honorary Secretary of the Executive Committee (the fore-runner of Council). Within the University, Emily helped win formal access for female students to Cambridge University examinations (achieved in 1881); she worked to improve women’s access to University lectures and demonstrations; and she was closely involved in successive efforts to gain women full membership to the University (sadly not achieved in her lifetime). Even after 1904 Emily continued to be very interested in Girton and in all its students’ activities and achievements.

Caption: Pages 2 and 3 from ‘Proposed College for women’, an appeal for contributions, circa late 1868 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 15/2/6).

Caption: Benslow House, 1869. Taken on a three-year lease on 30 September, Emily said the house had a ‘foundation of plainness and solidity’ (archive reference: GCPH 3/23/1).

Caption: Photograph of the first five students at Hitchin, 1869. (Back Row, L to R): Sarah Woodhead; Anna Lloyd; Louisa Lumsden. (Seated, L to R): Emily Caroline Gibson; Isabella Townshend (archive reference: GCPH 7/2/1/2a).

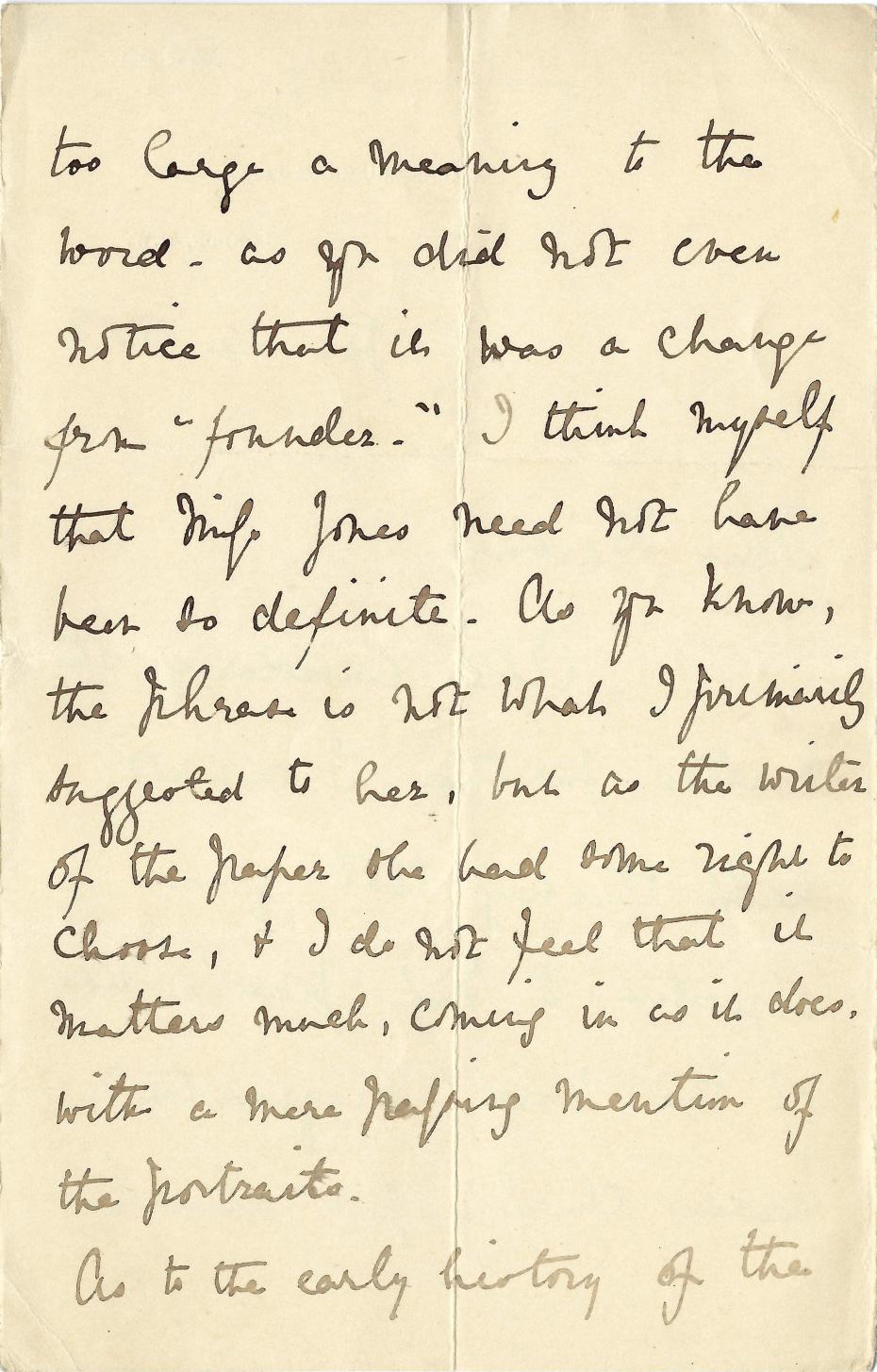

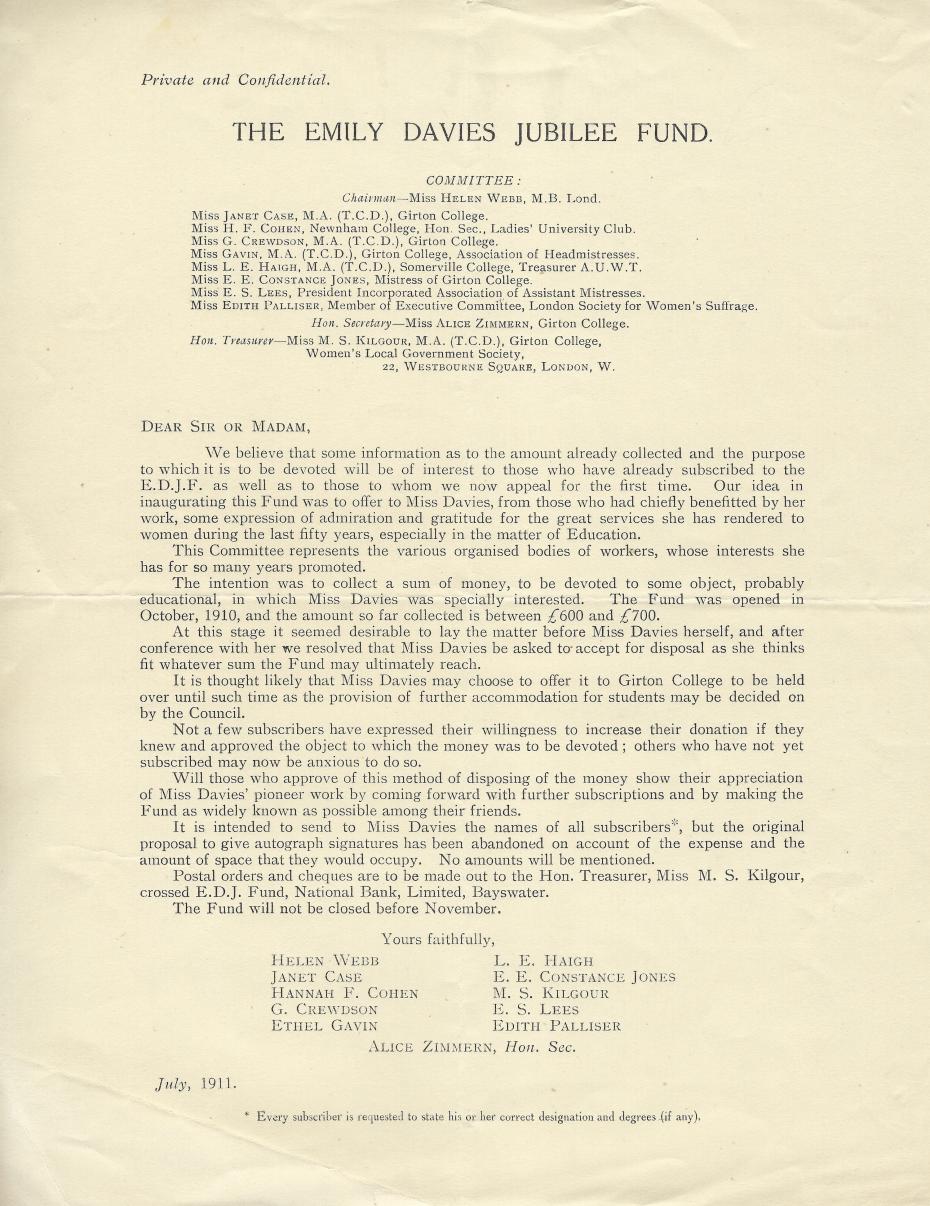

The ‘Originator’ or the ‘Founder’ of Girton College

November 1882 saw the publication of a short pamphlet: ‘Life at Girton College by a Girton Student’. The author noted that among the portraits in the Dining Hall (now Old Hall) was one of ‘…Miss Emily Davies, the originator of the College…’.

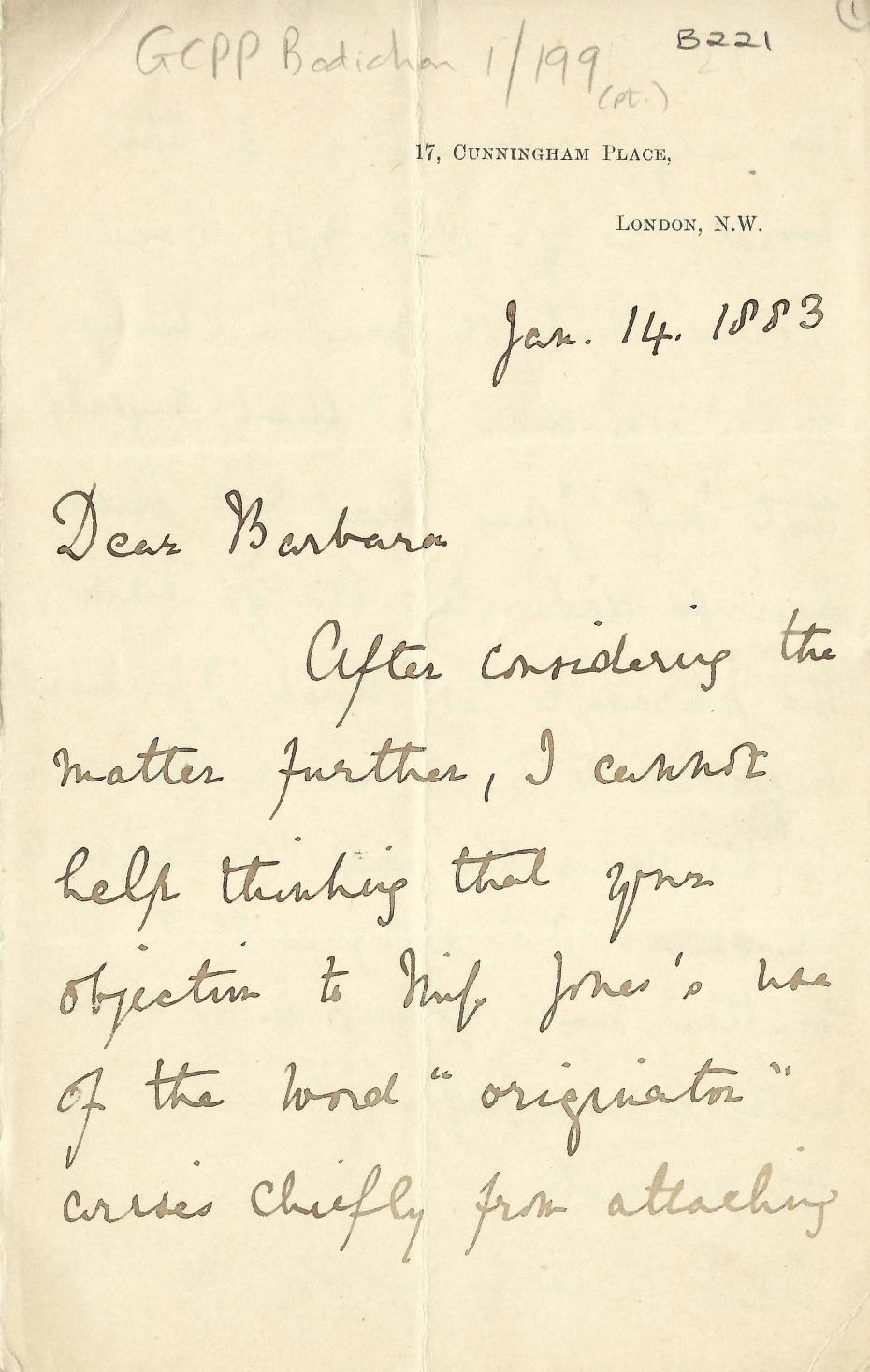

This caused consternation among the family and friends of Barbara Bodichon, who was not mentioned at all in the pamphlet. They were particularly shocked that there was no acknowledgement of Barbara’s role in Girton’s foundation. Some felt that Emily was setting herself out publicly as the sole ‘originator’ of the College. Although Barbara’s supporters did not want to cause a public scandal, several appear to have written privately to Emily on the subject. This caused Emily to write to Barbara, revealing that the author of the pamphlet was future Mistress E E Constance Jones, and that she and Emily had discussed the text before it was published.

In December 1882, Emily wrote to Barbara: ‘…I am sorry to hear that exception has been taken to the use of the word “originator”. The phrase to which I objected was “the founder of the College”. I asked Miss Jones to say instead “one of the founders” adding that if she did not like that, I thought there would be no harm in putting “originator”… To my mind, the word indicates the person who proposes a thing and gets others to help in carrying it out. Perhaps your friends have taken it as synonymous with “founder” – which I understand as meaning a different thing.’

After learning that Barbara was ‘still not satisfied’ with this explanation, Emily wrote to her again, in mid-January 1883: ‘… After considering the matter further I cannot help thinking that your objection to Miss Jones’s use of the word “originator” arises chiefly from attaching too large a meaning to the word – as you did not even notice it was a change from “founder”…’. Emily went on to emphasise that the idea of the College came to her after a meeting of Schoolmistresses at Manchester on 6 October 1866 and not, as Barbara suggested, during Emily’s visit to her in August 1867. Emily listed the work she undertook between October 1866 and August 1867. Her letter to Barbara concluded by saying: ‘… I have a sort of intermittent Diary, recording things close during 1867. I dare say you would like some day to see this and other old documents’.

Emily’s account of events in late 1866 and early 1867 is borne out by other sources, not least the prospectuses of the first half of 1867. However, it is interesting that if (which we cannot know) she saw E E Constance Jones’ entire text before it was published, she did not suggest some inclusion of Barbara’s name.

Caption: Part of a letter from Emily to Barbara Bodichon, regarding the issue of Emily being called the ‘originator’ of the College, 14 January 1883 (archive (archive reference: GCPP Bodichon 1/199pt).

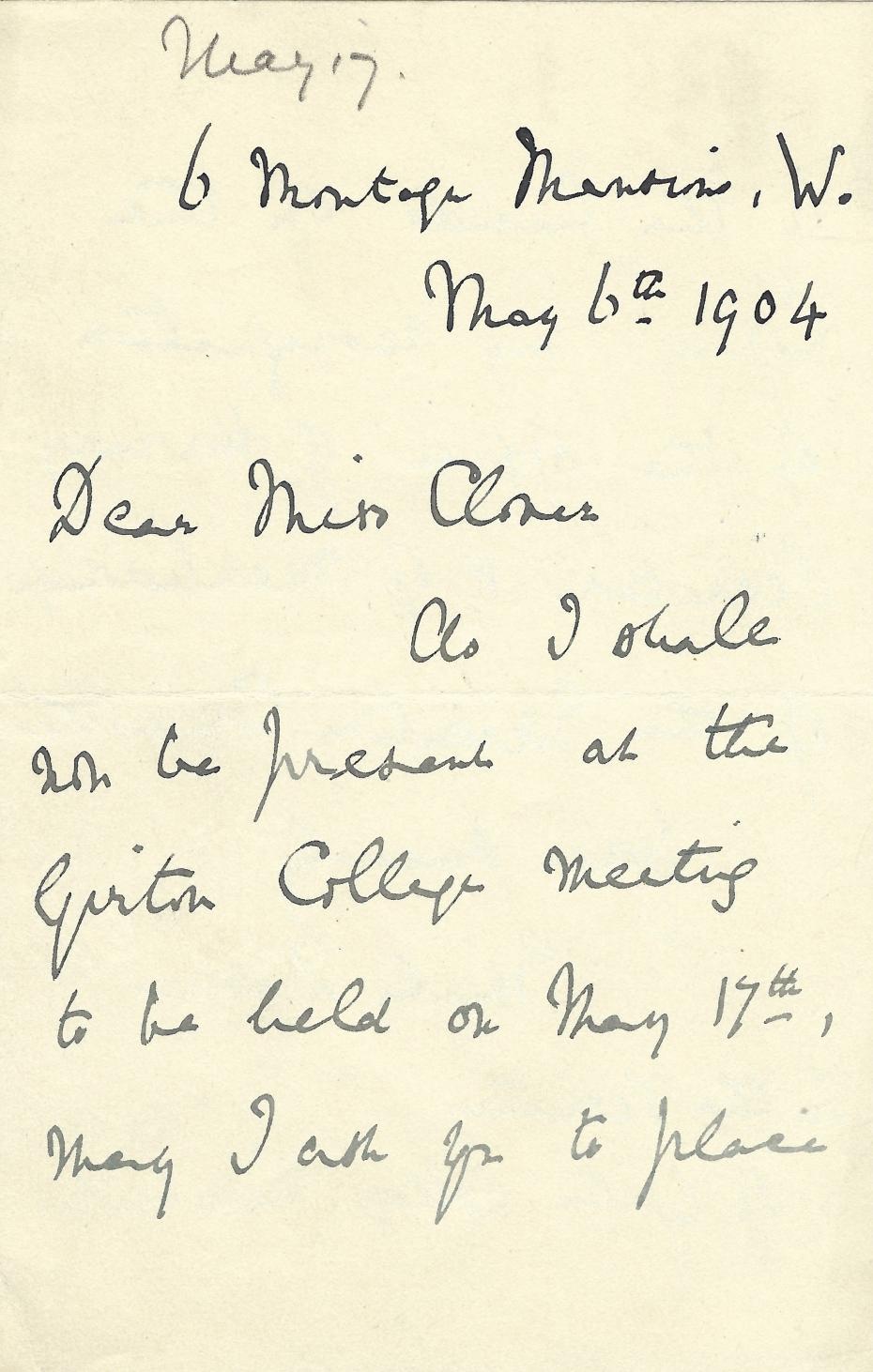

Emily’s resignation

In May 1904, Emily Davies sent a letter to Girton formally resigning her position as Honorary Secretary of the College and her membership of the Executive Committee (fore-runner of Council). Despite being asked to reconsider, she wrote to say she was unable to withdraw her resignation. Emily remained a ‘Member’ of College until her death, and continued to care deeply about its progress and its students. But she stopped attending the Executive Committee and from 1904 no longer took a direct role in College governance and decision-making.

This resignation was in part linked to Emily’s advancing years (she was now 74), her very long service to the College, and her desire to spend more time on other causes, including women’s suffrage. But it was also connected to disagreements that had grown since the mid-1890s between Emily and younger Girtonians over the future direction of the College. Among those challenging some of Emily’s views and decisions were a number of members of the Girton ‘Staff’ (fore-runners of Fellows) and some leading former students in the Association of Certificated Students (predecessor of The Roll).

Issues causing disagreement included the extent of the building work of 1899–1902 and any idea of further building before Girton’s sizeable debt was reduced. In addition, some Staff and former students wanted to see College give more support to ‘advanced’ academic work. They argued for new resident Research studentships. There was also growing pressure to reform Girton’s London-based governing structures to give greater powers to committees in College and a stronger voice for the Mistress, members of the Staff, and former students.

All these suggestions troubled Emily, who felt they were premature. By 1904, after some difficult years and the very intense work of the building programme of 1899–1902, Emily decided the best course was for her to resign. However, she very much wanted to keep her reasons for this as private as possible and to avoid any public appearance of a rupture. She urged her friends to talk ‘somewhat vaguely’ of how much College business had been moving to Girton in recent years and the appropriateness, therefore, of more Cambridge names appearing on its committees. They could, she said, ‘if necessary’ remind people that she had not withdrawn from membership of the College.

Caption: Emily’s letter of resignation addressed to Mary Clover, the Secretary of the College, 6 May 1904 (archive reference: GCAR 2/5/6/1/1pt).

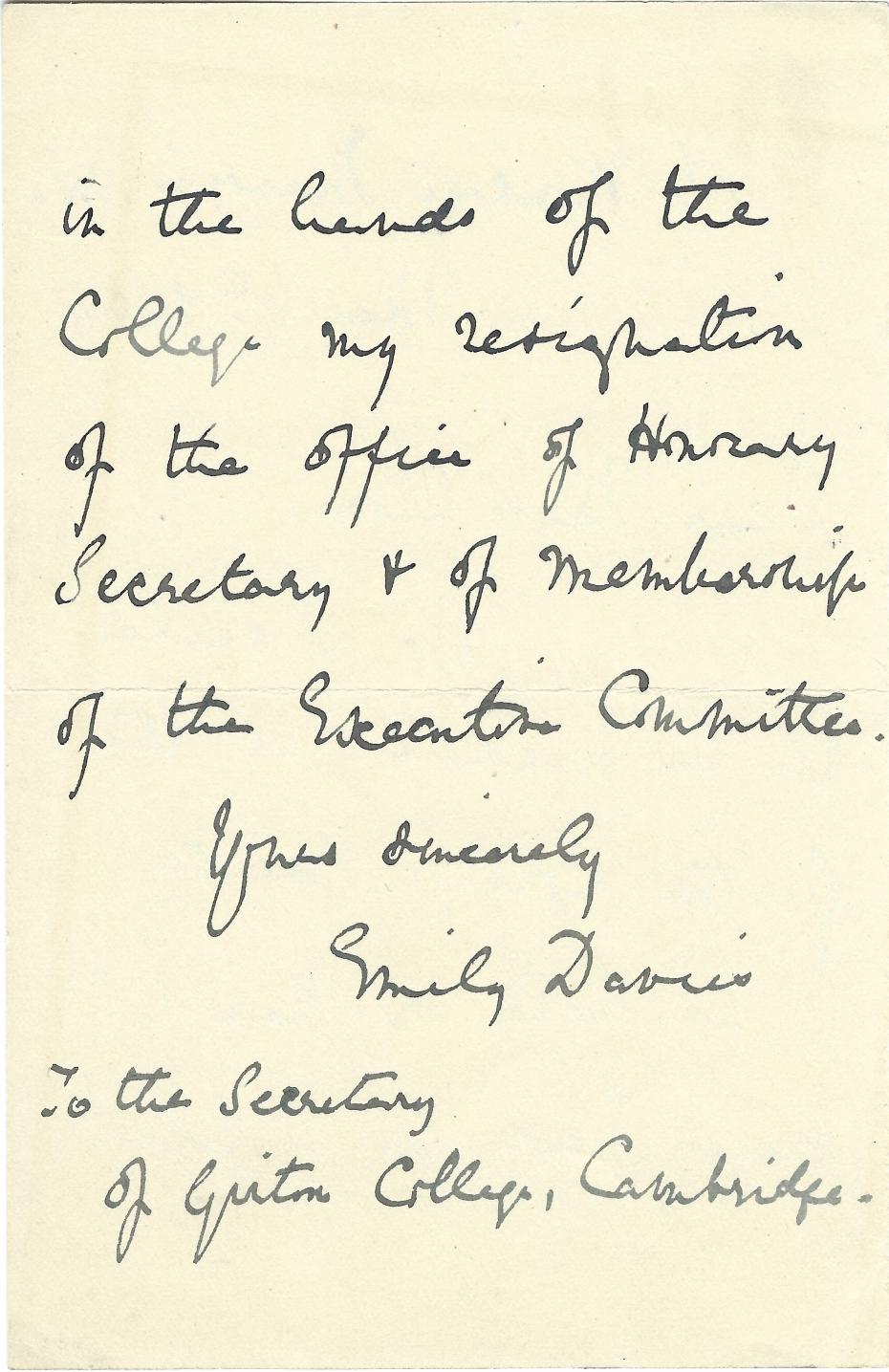

The Emily Davies Jubilee Fund

In October 1910, a London-based committee was formed to raise money for the ‘Emily Davies Jubilee Fund’. The aim was to recognise the many services, particularly in the sphere of education, that Emily, now 80 years old, had rendered to women since moving to London in 1862. The committee, which included several Girtonians, intended that Emily would donate the money raised to a cause in which she was ‘specially interested’.

On Wednesday 7 February 1912, E E Constance Jones formally presented £735 to Emily, together with a book listing the Fund’s 1,344 ‘subscribers’. She also announced that Girton had named the oldest part of College after her, and had placed a plaque over the original entrance bearing the words ‘Emily Davies Court’. Emily, delighted at the gift, soon wrote formally to the College offering to donate the money, along with a promised £1,000 from Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and another £1,000 from herself, to be put towards building further student accommodation at Girton.

However, the response from the College Council shocked Emily and her supporters. Council wrote that they could not ‘at present see their way to make provision for an increased number of students’, nor did they feel able ‘to pledge their successors to any given form or date of building’ by the creation of a building fund ‘allocated to one purpose only’. They asked if her gift could be the nucleus of a fund ‘to be used not necessarily for rooms for students, but for such additions to the College Buildings as may be determined upon in the future’. Emily refused this offer.

There followed a lot of frantic behind-the-scenes negotiations and some recriminations. Fearing it would become public that a donation had been refused, a compromise was finally reached. In November 1912, the Girton Report was able to record that £735 ‘has been received from Miss Davies’ and with her consent was ‘to be held by the Council of the College as the nucleus of a Fund for providing increased accommodation for students, such extension to be undertaken when the Council may see fit’. It also noted the receipt of £1,000 from Mrs Garrett Anderson, £100 from Miss Kilgour (a Girtonian and close friend of Emily), £1,000 from the Countess of Carlisle, and the ‘promise of a further contribution of £1,000 from Miss Davies’. This £1,000 from Emily does not appear to have been received before her death in 1921.

The building project Emily so passionately wanted was finally undertaken in the 1930s and saw the construction of New Wing, the Hyphen and the new Library.

Flyer for the Emily Davies Jubilee Fund, 1911. The flyer suggests the fund would be used for ‘further accommodation for students’, although this had not yet been fully agreed within the College (archive reference: GCAR 2/5/6/1/1pt).

Girton records the death of Emily Davies

The Girton [Annual] Report of November 1921 recorded the death of Emily Davies earlier that year: ‘By the death of Miss Emily Davies on 13 July, the College loses the last surviving founder, to whose initiative and perseverance it owes its existence … later generations cannot easily realise the untiring devotion and courage with which Miss Davies laboured in the cause … Miss Davies aimed from the first at … [the College’s] inclusion in the University, and she pursued this purpose with unfaltering zeal and devotion’.

Caption: ‘The work of Miss Emily Davies’, from the Times Literary Supplement, 13 August 1921. This article illustrates Emily’s continuing interest in the College and its achievements right up to her death (archive reference: GCAS 2/6/1pt).

Caption: Photograph of Emily Davies by an unknown photographer, circa 1915 (archive reference: GCPH 5/4/7).

This exhibition draws from many printed and manuscript sources, including:

- The personal papers of Emily Davies (archive reference: GCPP Davies): https://archivesearch.lib.cam.ac.uk/repositories/19/archival_objects/370725

- The personal papers of Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (archive reference: GCPP Bodichon): https://archivesearch.lib.cam.ac.uk/repositories/19/archival_objects/370704

- The College records (archive reference: GCGC and GCAR).

- Stephen, Barbara, Emily Davies and Girton College. London: Constable & Co., 1927.

- Hirsch, Pam, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, 1827-1891: feminist, artist and rebel. London: Chatto & Windus, 1998.

- Crawford, Elizabeth, Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their circle, London: Francis Boutle, 2002.