Girton was established in 1869 by Emily Davies with the support of a small group of exceptional men and women like Barbara Bodichon, Sedley Taylor and Henry Tomkinson. This was a daring initiative that proclaimed a fierce belief in equality of opportunity and equality of access to higher education. In its early days the growth of the College depended exclusively on donations. It was not until nine years after its foundation that Girton could afford more than one resident lecturer! Perhaps the most transformative gift in the early years of the College came from Jane Catherine Gamble, who left a residuary legacy of £19,000 (a sum of close to £2 million at today’s prices). It was this gift that allowed the College to build Tower Wing, including the famous square tower, and to buy the land which extended the estate to Girton Road. This enabled the College to transform the grounds from farmland to a park landscape, making Girton quite unlike the city centre colleges.

Gifts in Wills continue to be of crucial importance to Girton; on average over one third of donations each year are from Gifts in Wills. Recognising that such gifts are essential to Girton’s future, more and more alumni, supporters and friends are choosing to remember the College in their Will. Here are some inspiring stories from Girtonians who have made the commitment to leave a legacy to the College and on the impact some past legacies have had.

Catherine Bailey (Crick, 1978)

Education has the power to transform lives. It is the great leveller; whatever one’s family background or circumstances. I benefited hugely from the excellence of a Girton education and believe that those who have benefited from the privilege of such an incredible opportunity should, if their later circumstances allow, try to find some way of giving back to the institution that set them on their path to success.

This will help to ensure that future generations have the same opportunities and quality of education as we did. As responsibility for funding higher education shifts from the public to private sphere, the American concept of ‘pay it forward’ – the idea that if one benefits from the goodness of others, one should consider giving further down the line if one is in the fortunate position of being able to do so – is more important today than it has ever been. Remembering Girton in my Will is a way I can help ensure that the next generation of Girtonians have access to the best that higher education has to offer.

Belinda Lewis (1998)

Studying at Cambridge was life-changing for me. It broadened my horizons immeasurably – academically, socially, and in terms of aspiration and self-confidence – but I spent a lot of time at the start feeling thoroughly overawed and questioning whether I ought to be there at all. Girton’s reassuringly down-to-earth atmosphere helped put me at ease and the College offered me a strong sense of community and belonging. By the time I left, I had built lasting friendships and the basis on which to carve out successful careers in banking and then the Civil Service.

I have decided to leave Girton a legacy so future generations can enjoy all the benefits the College has to offer: for me, these included meeting people with a completely different background and world view; the chance to try a huge range of new sports, hobbies and interests; and discovering an environment where ability and dedication were the only attributes required to succeed. Those benefits are enduring and I’m very glad to offer something lasting in return.

Margaret Mountford (Gamble, 1970)

I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Girton. It could have been a daunting experience but the College provided a friendly and supportive environment, with Fellows who, I felt, actually cared whether I was happy or understood what I was studying, while maintaining the academic rigour expected of a Cambridge degree. I believe that I owe my career as a City solicitor, and my success in it, to my time at Girton. Having been an undergraduate in the 1970s, I received a first-rate education that was entirely free. I have left the College a legacy because I want to help put it on a firm financial footing so that others, in years to come, can benefit, as I did, from what Girton can offer. I hope that many of you reading this will do so too, as a “thank-you” for what Girton did for us and a commitment to the future.

Music and Legacies

Twenty years ago a benefactor nearing the end of her life bequeathed us the Austin and Hope Pilkington Music Fellowship. Thanks to this catalyst, Girton today has a flourishing mixed voice choir, an array of instrumental ensembles and a vibrant classical and popular music scene. Thanks to the foresight of a single, visionary donor, students from all subjects have every opportunity to work with an outstanding complement of professional musicians.

A Gift with a Global Reach

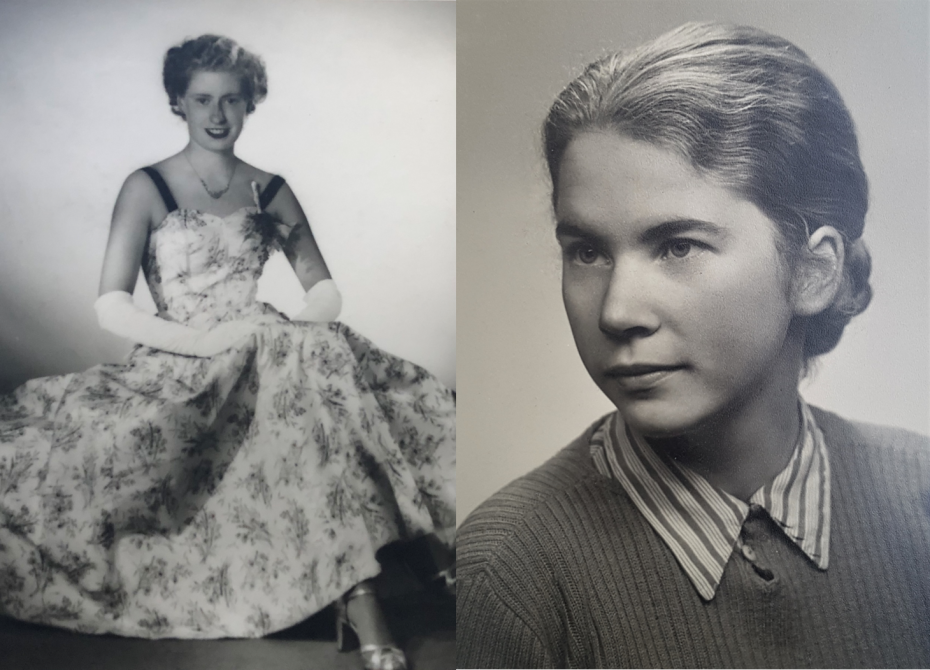

Family, friends and colleagues of Rosalie Crawford (née Duckitt) 1930–2020 describe her as intellectually curious, meticulous, a cryptic-crossword fan, and an avid traveller—journeying to all corners of the globe learning about different cultures, flora and fauna.

Rosalie was born in Hong Kong and a few years later her family moved to Shanghai. Her life changed quite dramatically after the outbreak of World War Two when on 8 December 1941, shortly before Rosalie’s 11th birthday, the Japanese Imperial Army entered and took control of the British and American parts of Shanghai. Rosalie and her family were taken prisoner and became internees in Yangchow C Camp, north of Shanghai. Life in the camp was difficult due to cramped living conditions, harsh weather, a poor diet and limited sanitation. The internees made the best of the situation—a makeshift health clinic and a school were established, and Rosalie attended regular lessons. She also recalled her father taking part in amateur dramatics to provide entertainment for the camp residents.

In 1945 the camp was liberated and Rosalie and her family returned to the UK where they settled in Yorkshire. Rosalie resumed her formal education (which had not suffered during her internment) at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and then gained a place at Girton in 1949, initially to read Economics before switching to Law—a subject which would become a lifelong passion. In addition to making lasting friendships at Girton, she gained Blues in cricket and hockey. After graduation Rosalie embarked upon a career in law, moving to Carlisle where she qualified as a solicitor. She remained at the same firm for her whole career and in true pioneering Girton spirit she became the first female partner at Cartmell Mawson and Main, as it was then known. Here she specialised in Conveyancing, Wills, Trusts, and Probate. Her work was meticulous. She had an eye for detail and was renowned for her ability to unravel complex points of law. Rosalie was also a very good teacher, eager to help others and pass on her understanding of the law.

Outside of her work, Rosalie loved to travel. Her adventures took her to Europe, North and South America, Australia, the Middle East and Far East, the foothills of the Himalayas and back to China and Hong Kong, all the while extending her knowledge of places, history and plants. At home her garden was her pride and joy, and she was known as a voracious reader with a thirst for knowledge.

In leaving a transformational gift to the College in her Will Rosalie will be enabling talented scholars to pursue their own intellectual passions. Each year, brilliant postgraduate applicants are unable to take up their offers, or are deterred from applying at all, owing to a lack of funding. Rosalie’s generosity will be used to leverage partnership funding and it will nearly double the number of Postgraduate Scholarships Girton can offer. Partnership funding has been sought in the Humanities and Sciences, at Master’s and PhD level, and for students both from the UK and abroad. This will mean Girton can welcome and support more postgraduate students than ever before. Their specialist knowledge and research is in great demand and so, with this gift, both students and society will benefit. In the words of the Postgraduate Awards Committee Chair, Dr Sophia Shellard-von Weikersthal, ‘This generous gift is transforming Girton’s ability to offer funding to academically outstanding and promising postgraduate students from a very diverse and international background, enhancing Girton’s efforts to widen participation. The Rosalie Crawford Scholars will strengthen our postgraduate community and greatly enrich the vibrant academic life at Girton.’

Made at Girton

Pippa (Girton 1969), Christopher, Joanna and Alison (Girton 1976) the children of Gillian Poulton (née Hunt, 1941) reflect on their mother’s life and her determination to make a difference.

Dr Gillian Hunt (1922–2016) was expected to ‘come out’ as a debutante and marry, but the social implications of this life did not appeal. In 1940, a near-miss by a bomb, dropped near her home outside Cambridge, strengthened our mother’s resolve to choose a different pathway.

Having never been taught any Physics or Chemistry, Gillian (Jill) worked hard to gain a place at Girton in 1941 to read Medical Sciences. She much enjoyed the ‘stimulating companionship of fellow students’. Away from the College she attended classes where the vast majority of students were male and the lecturers would address the audience as ‘gentlemen’. The men wore gowns which, at the time, women were not entitled to do, and comments were made when the women entered class. However, Jill remarked ‘I felt so privileged to be a student at Cambridge that this did not worry me in the least.’ Under wartime regulations she completed her undergraduate degree in two years before undertaking her clinical studies at the West London Hospital – only after being rejected from Guy’s Hospital, London where the then Dean responded ‘Women medical students? Over my dead body.’

The war meant hospitals were short-handed so Jill’s duties extended to acting as a hospital porter, fire-watcher, and x-ray technician. Once past the halfway point of their clinical studies, if the hospital was short of doctors, the medical students were called upon as hospital locums, something our mother described as ‘excellent experience for me, but not necessarily so for the patients.’

In 1949 Jill married psychologist Christopher Poulton and they bought a house in Cambridge. She juggled family life (four children, three of whom followed her into medicine, two via Girton College) with her professional work: a mixture of part-time appointments and research. Together with our father she undertook research on fatigue in junior hospital doctors and how sleep deprivation impaired performance. Their findings underpinned subsequent changes to the national guidelines for on-call rotas and the experience taught her much about how to do research, especially the importance of getting the statistics right.

In 1970 Jill was asked to be an independent observer for an ongoing study, started in 1963, of 117 children treated for open spina bifida, a condition where a baby’s spine and spinal cord do not develop properly in the womb. The study followed the group from birth and became Jill’s major lifetime interest for almost 50 years, and Girton played a small role in helping Jill conduct her work by offering her a Bye-Fellowship from 1975–77. The long follow-up of this study enabled her to discover which patients were likely to survive, walk, function independently and have the best life outcomes, and resulted in some 32 publications. In an interview with her granddaughter, Rosalind McLean, for the BMJ, Jill talks about the struggles of conducting her research in her 70s and not being part of a research group: ’…I was never paid a salary. However, as it was the only complete cohort of people with spina bifida followed up from birth I thought the research was so important I couldn’t stop.’

In 2012, aged 90, Jill was awarded her Cambridge MD on the basis of her published research. Her daughter Alison Poulton (1976) had her MD conferred at the same congregation making for a very memorable, and possibly unprecedented, occasion. Jill will be remembered as a kind, cheerful, loyal, much-respected wife, mother, doctor and member of her local community, and her memory lives on in her four children, 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Our mother felt Girton made her by giving her the chance to do Medicine (despite having had little opportunity to do much science at school), and to learn to think critically. Her gratitude is reflected in her support of the College, not least by remembering Girton in her Will so that other talented scholars may have the life-changing opportunity she so enjoyed.

In Memory

The College is always enormously grateful to receive gifts in memory of a Girtonian. These gifts honour a life and help others at the same time. Recently two such gifts have been received and these are set to transform lives.

Margaret Tyler (née Hughes) 1934–2018

Margaret (Geography 1953) greatly enjoyed her time at Girton and Cambridge. ‘Being an only child I enjoyed the company of so many intelligent youngsters in my age group who came from all over Britain and abroad.’ After graduation Margaret went on to teach Geography and her family describe her as a vivacious person who enjoyed travelling, painting and the outdoor life. Margaret’s passion for Geography was present on every family trip and her sons, David and Richard, recall fondly her efforts to teach them about the world around them.

Margaret’s husband, Colin Tyler (they met during their undergraduate days at Cambridge), has very generously made a gift in memory of her. The gift will endow the Margaret Tyler Research Fellowship in Geography, an early-career position that will help the incumbent establish a world-class research profile and gain teaching experience to form an all-important first step of their academic career.

Margaret’s son David comments ‘Mum thoroughly enjoyed her three years studying Geography at Cambridge in the decade after the war as better opportunities opened up for women. She was always interested in geology, geographical features of the landscape, plants and the outdoor life. Dad and the family feel that it is very fitting that he has been able to set up this endowment in Girton’s 150th year. Richard and I are very proud of our parents’ achievement considering they both came from such humble, working class backgrounds.’

This exceptional gift will be game-changing in Girton’s ability to attract and support Geography students and underwrite career development in geographical research.

Rhona Beare 1934–2018

Nancy Gregory describes her sister, Rhona (Classics 1954), as a ‘one-off’. Her talents were many: academic and artistic, including various types of needlework. Knitting enabled her to study a fragment of an ancient Roman sock and work out the type of stitches the Romans used. She could read Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, French and German. She decrypted a code used by a messenger of Queen Elizabeth I, this code requiring knowledge of the Greek alphabet and Norman French.

After Girton, and before emigrating to Australia to lecture, Rhona studied for a PhD in Classics at the University of Exeter. She also took up medieval history and while at Exeter she entered into lively correspondence with J R R Tolkien.

Rhona’s greatest joy was reading books. She devoured books of all kinds but above all detective stories. She liked to visit the places mentioned by her favourite authors, once visiting the Tower of London just to see the precise turret from which some villain is said to have shot his victim. In her last months Rhona requested Dante’s Divine Comedy in the original Italian, and the New Testament in Greek, because “the text was clearer”.

To mark such an extraordinary life Nancy has made a gift in memory of Rhona to establish a graduate award in Classics. Higher degrees are a prerequisite for successful entry to many careers not just in academia. There is limited funding for postgraduate education, and every year applicants of enormous potential cannot take up their place at Girton owing to insufficient funding. This award, which will carry Rhona’s name, will enable a talented student to continue with their studies in Classics and set themselves on a pathway to a very bright future.

Our Mother’s Legacy

Ceri and Gwyneira Isaac, the daughters of Barbara Isaac (née Miller), who came up to Girton to read English in 1955, share their mother’s life story and the lasting influence Girton had on her, and on them.

Barbara Isaac (1936–2015) once told her daughters a story of her visit to a career counsellor the year she was graduating from Girton. She spoke with the counsellor about her ideas for a career in archaeology and museums and was told that venturing into archaeology would be risky, but that there were plenty of much more suitable jobs in schools and libraries. For Barbara this was clearly an invitation to explore all the risks that archaeology could possibly throw at her. She promptly got a job at the Sheffield Museum and, soon after, began graduate studies at the Institute of Archaeology in London. Whenever possible she joined archaeological excavations, such as at Creswell Crags where she met Glynn Ll. Isaac (Peterhouse), a quaternary archaeologist whom she later joined in Kenya to aid him in his research on human origins at Olorgesailie. The two became inseparable partners in both research and life, marrying in 1962 and introducing their firstborn daughter, Ceri, to living in the East African bush. In 1966, the year their second daughter Gwyneira was born, Glynn accepted a faculty position at the University of California, Berkeley, and Barbara put her energies into contributing to and illustrating publications, running the laboratory and overseeing research logistics, including the challenges of supervising graduate students who joined them in the remote field site where they worked in northern Kenya.

After the tragic and early death of Glynn in 1985, Barbara embarked on a new career at Harvard University, where the family had recently relocated two years prior to Glynn’s death. She started in the basement of the Peabody Museum as an assistant photo-archivist, and in short order became director of the Photographic Archives, and Associate Director of the Peabody Museum in 1990. This included overseeing Harvard University’s compliance with the newly introduced Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). With the mandated return of culturally affiliated human remains and sacred objects to Native American communities came ethical and political responsibilities that many archaeologists and museum staff across the US had, until then, either disputed or avoided. Barbara saw NAGPRA as an opportunity to learn about Native American culture and philosophy, as well as to begin training the next generation of archaeologists and Native scholars in collaborative and cross-cultural museology. In the same way that she had gathered together and fostered the archaeology research community working in East Africa, she became an advocate and host for Native scholars at Harvard, many of whom remained indispensable friends throughout her life.

'Food and knowledge sharing' was initially a research topic in human origins that interested Glynn and Barbara but it became a way of life which Barbara embraced, and turned into a world of lasting friendships that she treasured and which kept her vital through her last days. Her Girton friends were some of the most important — Rosemary Hollingworth, Mary Newsome, Ann Parsons, Mary Dyson, Judith Rodden, Christine Butler — to name but a few. In 2003, Barbara took her youngest daughter, Gwyneira, to a Girton reunion. On the way there, Gwyneira confessed she had brought numerous books to read, as she anticipated not having much in common with this horde of ‘old girls’. The weekend, however, became an eye-opener in just how plucky, unconventional, and truly pioneering this group of Girton women are and they soon became her vital role models.

Through friendships with other women, our mothers show and share with us the remarkable things that women are achieving — academically, professionally and ethically — and these networks and knowledge become central to how we see our futures and shape our lives. We were very pleased to be able to tell Girton of the placing of a collection of Barbara’s poetry in the College Archive, as well as the news of a gift in her Will. We will long remember and cherish the Girton stories and friendships our mother has shared with us.